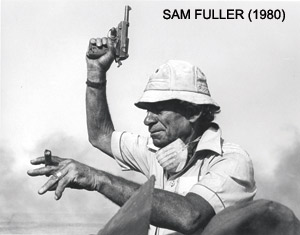

BY GARY GIDDINS

(Credit: DGA Archives/United Artists)

(Credit: DGA Archives/United Artists)

Aristotle, of all people, is cited in the first two films written and directed by the poet of pulp Samuel Fuller. He is quoted by the theater manager in I Shot Jesse James ("No one loves the man whom he fears") and dutifully recited by the child fiancée in The Baron of Arizona ("Dignity consists not in possessing honors, but in deserving them"). Aristotle and Fuller. As Dracula might have said, "What music they make."

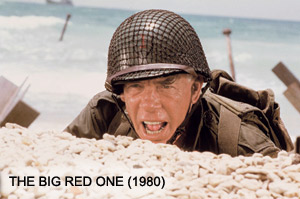

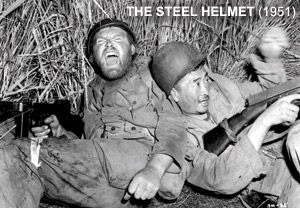

Of course, the incongruity is quietly hilarious. No storyteller was less Aristotelian than Sam Fuller, the self-mythologizing, bantamweight filmmaker who once insisted on smoking cigars two inches longer than those of Darryl F. Zanuck. Fuller had little use for the Greek's primary theatrical principle—the one about a beginning, middle, and end. He preferred to start in the middle and end in a circle of futility, especially in his peerless war films, such as The Steel Helmet, which closes with the legend, "There is no end to this story," or The Big Red One, which begins and ends on the same chord of lethal error.

Nor did he pay much mind to traditional ideas of tragic stature and denouement. Fuller's heroes are grifters, military retreads, prostitutes, gunmen, renegades, and misanthropes; early on, he made a film (Park Row) lauding members of his first profession, journalism, but he later sentenced the journalist-hero of Shock Corridor to a straitjacket. Madness is a recurring theme in Fuller's pictures. As he sees it, madness is separated from socially condoned behavior by a fabric as thin as the one between crime and salvation. In Pickup on South Street, Thelma Ritter plays a righteous informer, honored as such by the very people she sells out. When she tells an immoral Commie, "You'd be doing me a big favor if you'd blow my head off," he does her the favor, thereby triggering his own destruction.

In retrospect, it's amazing that Fuller had the Hollywood career he did. Thriving on his own terms from 1949 until 1964, he wrote and directed 17 films, most of which made money. Then he slipped into a long turnaround of failed, butchered, and unreleased projects, reinventing himself as cinema's grizzled anecdotalist-prophet, offering his own aesthetic principle. ("The film is like a battleground," he barked in Jean-Luc Godard's Pierrot le fou. "Love, hate, action, violence, death—in one word, emotion!") Refusing to say die, he rebounded and completed his masterpiece, The Big Red One, in 1980. It, too, was butchered; the documentarian and film critic Richard Schickel later restored 50 minutes for a triumphant premiere at the 2004 New York Film Festival.

(Credit: Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

(Credit: Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

Fuller is a favorite of baby-boom filmmakers, who saw his pictures as kids and never forgot the experience. (My first was Merrill's Marauders, one of the most grueling movie memories of my childhood; my father observed that his three years in the Philippines were less exhausting than Fuller's trek through Burmese swamps.) Yet much of Fuller's work had not been available on home video until this year. Thanks to DVD releases from Criterion and 20th Century Fox, we can now see seven of his first eight pictures, covering the years 1949-55.

Criterion's no-frills Eclipse series recently put out The First Films of Samuel Fuller, collecting I Shot Jesse James (1949), The Baron of Arizona (1950), and The Steel Helmet (1951). Except for a brief distortion at the 102-minute mark of Jesse James, the transfers are clean and sharp. The Criterion catalog has long offered pristine editions of Pickup on South Street (1953), and the later epics in dementia, Shock Corridor (1963) and The Naked Kiss (1964). Fox added Fixed Bayonets! (1951) and Hell and High Water (1954) to its earlier releases of House of Bamboo (1955) and Forty Guns (1957); Warner Bros. offers an exemplary presentation of The Big Red One. Still missing on DVD are Park Row (1952) and later expressions of Fuller's lurid impudence, notably Run of the Arrow and China Gate (both 1957), Verboten! (1959), The Crimson Kimono (1959), Underworld USA (1961), and Merrill's Marauders (1962). Criterion has added to its future schedule the much banned and battered inquiry into racism, and White Dog (1982). Only Hell and High Water, a submarine misfire, is expendable. The others are genuine depth charges—vital, original, outrageous, and prescient.

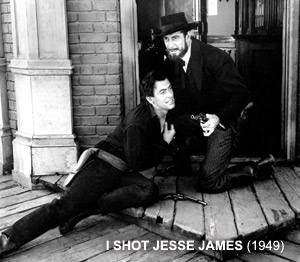

Born in Worcester, Mass., in 1912 to immigrant Jews, Fuller worked as a New York crime reporter at 17. He wrote pulp novels, served with distinction as an infantryman during the war (Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart), and then nosed around Hollywood for years writing scripts. Independent producer Robert L. Lippert offered Fuller his own film, and at the end of a decade renowned for resplendent directorial debuts (Welles, Huston, Minnelli, Wilder), Fuller made his mark with a B-picture in an overcrowded genre. I Shot Jesse James was a psychosexual, sympathetic look at Bob Ford, the "dirty little coward" who murdered the absurdly romanticized outlaw.

(Credit: AMPAS/Screen Guild Productions, Inc.)

(Credit: AMPAS/Screen Guild Productions, Inc.)

From the first silent close-ups of the two men, one with sweat on his upper lip, preceding a master shot that reveals them facing off during a bank robbery, to the eerie finish, in which a dying Ford declares his love not for the woman cradling him in her arms, but for James, the film reflects the unmistakable vision of a man marinated in the quick fixes, vain sensationalism, and tattered truths of hard-nosed newspapering. Fuller found many of his best stories and characters during the war, but he learned style in the tabloids—which is not to say that he wasn't a natural filmmaker.

Fuller was an intensely pictorial director. His obsessive close-ups stem from the belief that if you look long and deep into faces, they will reveal nuance not found in the script. His long takes, which in fight scenes required actors to do the work of stuntmen, elaborate the plot with a dizzying sense of spatial dynamics, sometimes requiring a performer to throw a punch at the camera. (Imagine what he might have done with 3-D.) Fuller's abrupt cutting between elaborate masters and invasive close-ups—surely it was he who taught Sergio Leone the power of shifty Cinemascope eyes—creates dislocation while emphasizing an obsessive need to show the action outside and imply the tumult inside.

Among his predecessors, the director Fuller most recalls is D.W. Griffith, mentioned only in passing in Fuller's posthumous memoir, A Third Face (published in 2002, five years after his death at 85). They both had an eye for tableau vivant arrangements of characters, a penchant for drumming up suspense by interlacing opposing actions, and a predilection for punctuating emotional flare-ups with close-ups. Griffith all but invented these techniques, spurred by practical considerations, but that's beside the point.

Fuller was as obsessed with race as any director of his generation. He dealt liberally and candidly with black/white racism (The Steel Helmet, China Gate, Shock Corridor), while elaborating on the compassionate exploration of prejudice between Occidentals and Orientals in Griffith's Broken Blossoms. Fuller tackled Japanese-American relations repeatedly. In The Steel Helmet, he broke Hollywood's silence about Japanese internment camps; in the sublime House of Bamboo (filmed in Tokyo with a blasting of colors to rival that of Ozu's Floating Weeds or Kurosawa's Ran), he contrasted a healthy affair between a Japanese woman and an American military cop with two deeply closeted male gangsters. He brought the fear of otherness home in The Crimson Kimono, which was advertised with a poster that screamed: "YES, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy!"

Yet the most profound tie between Griffith and Fuller is one of narrative attitude. Each man thrived on pulp. Griffith preferred a melodramatic, sentimental kind that flowered at the turn of the 20th century, mixing the Gothic and penny dreadful traditions. Fuller brought the age of Black Mask, comics, and scandal sheets alive with a style that perfectly complemented what he habitually called his "yarns."

Most classic noir films of the 1940s and 1950s, whatever their literary origins, were filmed by craftsmen who polished the material to a glossy sheen, hoping by virtue of their artistry to graduate to a better class of picture. Not Fuller. You cannot fake a pulp imagination. No film school graduate can replicate lines that flowed from his typewriter, including the left-field borrowings from Aristotle.

Choosing memorable Fuller lines is like assembling a bouquet: "It's you she's sorry for, but it's him she wants." "If you die, I'll kill ya." "Don't shoot! I'm out of bullets." "Now I know what I was looking for—a woman who loves me for who I am." "Each man has his own reason for living and his own price for dying." After Jean Peters comes up from a deep kiss and tells Richard Widmark, "I really like you," Widmark says, "Yeah? Why? Everybody likes everybody when they're kissing."

(Credit: AMPAS/Lippert Pictures, Inc.)

(Credit: AMPAS/Lippert Pictures, Inc.)

Yet dialog is the least of it. Fuller's inventiveness extends to music (the orchestra "shoots" Jesse James with three brass chords before Bob Ford fires a shot) and photography (a thunder clap and lightning flash accompany Vincent Price's entrance in The Baron of Arizona). Then there are the wrinkles in the plots, with their mounting ironies, sudden breakouts of hitting or kissing or shooting, and pure storytelling orneriness. The true man of pulp can have his cake and eat it twice.

In the 1950s, Fuller wanted to make a film about a criminal syndicate run by ex-army personnel in accordance with military regulations. The project fell apart, so Darryl Zanuck, who admired and sponsored Fuller, suggested he remake the 1948 film The Street with No Name—in Japan, if he preferred. Fuller simply adapted his military gang story to Tokyo, which in House of Bamboo is mysteriously ruled by Robert Ryan, with the help of sexually maladroit henchmen and jitterbugging "kimono girls." On the ground, the movie makes no sense. But in Pulpland, where Sam Fuller operates, it is absolutely spellbinding. You can either fend his films off with invocations of logic and good taste, or give yourself up to his mania for truth, justice, and the American way.