BY ALEX BEN BLOCK

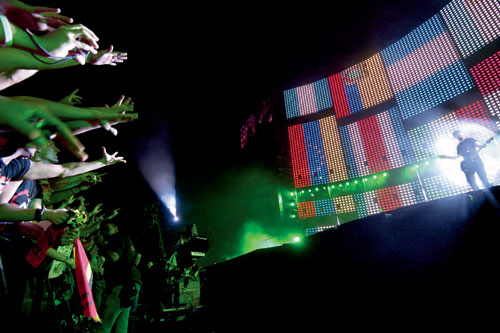

IT'S LIVE: Shooting in 3D allowed the directors of U2 3D to capture the

IT'S LIVE: Shooting in 3D allowed the directors of U2 3D to capture the

crowd and depth of the performance in one shot. (Credit: 3ality)

When Bono, the lead singer of the Irish band U2, wails out "Sometimes you can't make it on your own," while guitarist Edge slams into high gear, and his drummer Larry Mullen is at full flail, most directors making a fan-friendly performance documentary would focus on one aspect of that performance, or do split screens. Not Catherine Owens. She wanted them all in one frame. She got it by shooting in the third dimension.

Owens, an Irish multimedia artist, painter and sculptor who makes her directorial debut on U2 3D as co-director with Mark Pellington, recalls cutting the scene together in both 2-D and 3-D. "There was a fantastic moment where, because we've got the depth to be able to do a performance on the front space of the screen, another performance in the middle space of the screen and a third performance coming through the back space of the screen, we were able to layer Edge's guitar solo into Bono's singing into the next shot, which is Larry the drummer, all in one sequence. So if you could imagine going from left to right in a normal 2-D edit, we were going from front to back in the 3-D edit."

U2 3D, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May, is expected to be the first of a new generation of live-action digital 3-D movies to hit theaters this fall, closely followed by Paramount's live action Beowulf, directed by Robert Zemeckis. That will be followed in 2008 by a 3-D live action movie based on Journey to the Center of the Earth, among others.

The modern digital 3-D process got a boost in 2005 with the success of Chicken Little and Polar Express, both of which did significantly more business in 3-D than in 2-D releases. Since then, every studio in Hollywood has put stereoscopic 3-D projects, both animated and live action, into development. Disney earlier this year released the CG time-travel adventure Meet the Robinsons, with 3-D again out-performing 2-D venues; and DreamWorks Animation plans to make all future animated movies in 3-D.

VISUAL ASSISTANCE: New plastic glasses are expected to

VISUAL ASSISTANCE: New plastic glasses are expected to

solve most viewing problems.

No director has been more at the forefront of the digital movement than Academy Award–winner James Cameron, who has been working on 3-D movies and documentaries and developing new cameras and editing techniques for seven years.

Cameron was drawn to digital 3-D because of the creative possibilities and the fact it offers something people can't get in home theaters. He admits the process adds costs but says so did the addition of color and sound.

For several years, Cameron lobbied exhibitors to invest in digital and 3-D but he still wasn't sure if they would respond when in 2006 he declared that his next big budget movie, Avatar, would be a live action film (with lots of CG effects) in digital 3-D (and 2-D in traditional venues).

"Filmmakers would say if the screens aren't there, the content won't be there," says Cameron. "So that's why I did what I did with Avatar and drove a stake in the ground and said this is going to be a 3-D film. We'll see where the chips fall. In terms of theaters, fortunately, it looks like it's working out."

A five-year-old Los Angeles company, Real D, is installing the digital 3-D systems. It expects to have 1,000 in theaters by the end of this year, close to 3,000 by the end of 2008 and nearly 5,000 by Memorial Day 2009. That's when Cameron's Avatar is scheduled to open. It is also the date DreamWorks says it will premiere its 3-D Monsters Vs. Aliens, raising speculation about whether there will be enough theaters.

THE FUTURIST: Avatar director James Cameron pioneered

THE FUTURIST: Avatar director James Cameron pioneered

a new generation of 3D cameras.

"The fact people are arguing this two years before the fact is wonderful," says Cameron, who experimented with 3-D going back to 1991's Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and the theme park attraction T2 3D: Battle Across Time. However, he wasn't happy with the technology at that time. It was only in 2000 that new digital systems emerged and opened his eyes to the possibilities.

The old style 3-D movies made on film could strain the eyes. "The digital technology is much more sophisticated at the stage of display," says Cameron. "The projectors are so much better, so much clearer, sharper, brighter, and the camera systems allow you to really be in complete control of the 3-D process."

Still there are limitations, says Cameron, including using very long lenses or doing a lot of fast cuts: "The further you drive the camera away from the physical subject, the less parallax you are going to get out of the image. If you love to have 12-18 frame cuts in a chop salad kind of action sequence, don't do it in stereo."

To properly capture digital 3-D, Cameron formed a joint venture with camera engineer Vince Pace, and they recruited Sony Corp. to build a new generation of 3-D cameras. Each has two lenses on one body, and a fiber-optic cable allowing handheld or Steadicam shots.

While 3-D lends itself to action and fantasy movies, Cameron believes it can also have value for other genres. After Avatar, he says his next movie will be a lower budget drama. "I'm going to shoot it in 3-D for a specific reason, because it's about two people who are in love with the ocean, as they are with each other," he explains, "so there are underwater scenes that will really allow the audience to feel what they feel. So again it is using 3-D to enhance the dramatic theme of the film. But it won't be used in a gimmicky way."

Of course, there were 3-D film fads in the 1950s and a revival in the 1980s, but they both fizzled. Digital 3-D became possible only after theaters began converting from film to digital projection. To show 3-D films, a rig, manufactured by Real D, swings into place on the digital projector that plays through a special filter onto a patented screen.

Key elements of the new 3-D projection technology were patented two decades ago, just as computer use was becoming widespread. It was initially developed for military applications, including aerial photography, and for use by the auto industry to create 3-D images in place of expensive physical car models. Using liquid crystal technology, StereoGraphics enhanced computer graphics to transmit separate images to the left and right eye, giving much deeper perspective.

"Think of us as a kind of turbo charger," says Josh Greer, president of Real D. "Start with a digital projector. Add a number of components from Real D with ghost noise-reduction technology. One of the big things that plagues 3-D images is ghosting. We can now electronically remove most of that ghosting before it ever hits the screen."

The new digital 3-D process has been winning converts. Even Steven Spielberg, who until now has shot and edited only on film, will produce and direct digital 3-D movies in a highly realistic form of CG. As part of filmmaking alliance, Spielberg and director Peter Jackson will make three pictures based on the international comic book character Tintin.

"Steven and I decided to add that one last element that will totally immerse the audience in the excitement of Tintin's adventures—and that is to produce these movies in full digital 3-D," said Jackson in a statement. "Just the thought of it makes me feel like a kid again."

Director Steven Anderson, who had developed Meet the Robinsons before it became a 3-D project, is another filmmaker who has embraced 3-D. "To be honest, my first reaction to the idea of making our movie in stereoscopic 3-D was to roll my eyes and say, 'Oh gee, it's just a gimmick. This is another studio-driven decision as opposed to an artistic decision.' To my surprise, the team was really quick to say, 'No that is not the case.' They said, 'The technology has advanced to a point where we can now actually control it from moment to moment. We can use it as a storytelling device, not as just a gimmick.'

STATE OF THE ART: Meet the Robinsons director Steven Anderson realized

STATE OF THE ART: Meet the Robinsons director Steven Anderson realized

3D was not just a gimmick. (Photo Credit: Disney Enterprises)

"It's not about every moment in the movie being at the same level of depth and having things poking from the screen," adds Anderson. "We can dial the depth back in the quieter moments. We dial the depth forward in more intense moments, or the more dramatic moments, or wherever we can help the storytelling. For me that was huge. So as soon as I heard that I said, 'I'm in.'"

Eric Brevig, director of a live-action 3-D science fiction adventure based on Journey to the Center of the Earth, for release by New Line Cinema in 2008, has been shooting with Cameron and Pace's Sony cameras. He says as a special effects artist making his directing debut, he relishes the ability to use depth to both compose in and to surprise the audience. "Because I had been a fan of 3-D since I was a kid, I knew that if you embrace the medium you can design your sequences to maximize the use of the media," he says. "Basically that means designing, blocking, structuring the story so you really give the audience a lot of 3-D. I would call it thrills, but that's not the right word. You take them to the extra dimension. Just as you would compose graphically in 2-D on the screen, you can compose 3-D in stereo."

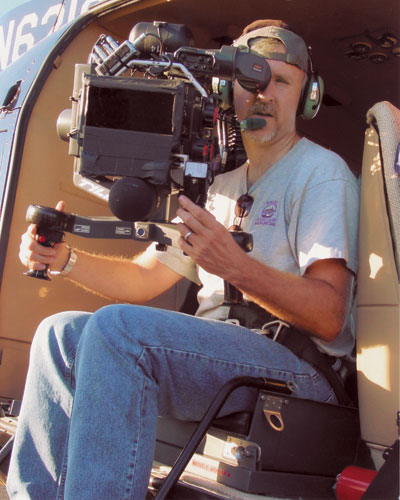

GOING DEEP: Eric Brevin (right) making his directorial debut on Journey

GOING DEEP: Eric Brevin (right) making his directorial debut on Journey

to the Center of the Earth used the depth of 3D to compose shots.The director also has another new challenge, adds Brevig: "You're manipulating the audience's eyeball muscles. You have control over where each of their eyes is going to be looking and you can use that for the forces of good or evil. The more times you force them to cross their eyes, or worse, go wall-eyed trying to watch your movie, the additive nature of that, after awhile, leads to eye fatigue. Then people will say, 'I just don't like 3-D movies. These glasses hurt my eyes.'"

Steve Schklair, a partner in 3ality Digital, which provides 3-D camera platforms, editing and postproduction, says the new 3-D plastic glasses solve most problems, but agrees it is up to filmmakers to get it right. "You really need to edit in 3-D, conform in 3-D, post-produce in 3-D to make a 3-D movie that works all the way through and is still efficient. We're not doing things on a frame-by-frame basis anymore. We have tools that are automated, that use image processing and image analysis to complete certain actions that we used to have to do frame by frame... We couldn't be posting what's going on in this U2 movie without these tool sets that have been built by doing post-work for awhile."

Moving beyond CG is a new phase for digital 3-D. "Meet the Robinsons was layers upon layers of composited animation. U2 was shot as live-action and it's a different effect," says Schklair. "There's more depth to the U2 movie because while we were shooting, we were able to control various elements of depth. There are a lot of scenes where we've pushed the depth out there, still comfortable to the eye, but it's a much deeper experience."

Owens, who had previously done multimedia design for U2, was recruited by Real D and 3ality to direct the first digital 3-D live-performance movie featuring U2 during the band's Vertigo tour of South America. Their biggest mistake, admits Owens, was in under-scheduling, especially postproduction. For instance, the editing took longer than expected after she realized that in 3-D "you can't do a hard cut. You've got to have some sort of dissolve to make it work for the eye. That was a significant limitation for a rock and roll performance. But it created a challenge. We decided to focus a lot more on our dissolve and our layers, so we made these quite complicated for those dramatic moments. In order to achieve that, the company had to develop significantly new software, so the development of the software went on a song-by- song basis."

Owens depended on Pellington to capture the live action and the technical team to handle the process, which allowed her to concentrate on creating the best movie. "A very large amount of generosity has to definitely go into a 3-D shoot," she explains. "People just kept saying, 'OK, you know what? None of this is what we thought. But, oh my God, it's so exciting. Let's just keep going.'"