BY ROB FELD

Bill Condon remembers seeing the original Broadway production of Dreamgirls from the back row of the Imperial Theatre on opening night in 1981. He was so enthralled he returned to see it “many, many times.” Then, after his successful adaptation of Chicago (directed by Rob Marshall), the time seemed ripe to tackle the show that had eluded filming for 25 years.

Bill Condon remembers seeing the original Broadway production of Dreamgirls from the back row of the Imperial Theatre on opening night in 1981. He was so enthralled he returned to see it “many, many times.” Then, after his successful adaptation of Chicago (directed by Rob Marshall), the time seemed ripe to tackle the show that had eluded filming for 25 years.

“I do think Chicago was my undergraduate education in musicals and there was a lot I learned there that I could apply to Dreamgirls,” says Condon. “One basic lesson was to keep narrative and story going through the songs; each character should always wind up in a different place at the end of the song from where they started.”

Condon had plenty of characters and narrative threads to juggle in the story loosely based on the rise of Motown and the pop stardom of Diana Ross and the Supremes. Jamie Foxx plays Curtis Taylor Jr., a Berry Gordy-type entrepreneur who discovers, nurtures and ultimately dominates their career.

On the way up, Curtis decides the only hope for getting his music on the radio is to pay off disc jockeys. The first part of the scene, as Curtis gambles to raise capital, is intercut with dance rehearsals for the “Steppin’ to the Bad Side” number. Below, Condon describes how he shot the scene as it finally explodes on the stage of the Apollo Theater, performed

by an electric Eddie Murphy as James “Thunder” Early.

Coming about 30 minutes into the story, “Steppin’ to the Bad Side” is one of the film’s most elaborate productions and key transitional points. “In its way,” says Condon, “it tells more story than any of the film’s other musical numbers.”

With so much story to convey in such a short time, every element becomes critical, especially color. Having realized that he won’t achieve his goals by playing it straight, Curtis decides to ‘step into the bad side,’ and we use red—the color of danger, of blood—as a dominant color to reflect that shift. In this shot, Curtis’ garage completes its transformation from car dealership to performance space. The heat lamps, which in an earlier scene were used to bake a paint job dry, are now lighting a dance rehearsal.

The mirrors are a gentle nod to another Michael Bennett creation, A Chorus Line. On stage, C.C. was a composer, but in the film he’s also the group’s choreographer, which allows us to introduce a full-on dance sequence while still remaining real. The lighting is also making a shift to something more theatrical, with the light coming through the windows becoming a little cooler than real daylight. Tobias Schliessler, our cinematographer, used a high-speed Tungsten stock, which, if you don’t correct it with a gel, creates that cooler feel. There’s no specific sense

of time of day here; it could be day or dusk.

The rehearsal is intercut with aerial shots of cities where the record is getting radio airplay. These brief nightscapes swoop and soar as the music builds. On stage, Dreamgirls wasn’t known as a huge dance show—the ‘dance’ came more from the way the set moved and from Michael Bennett’s incredibly kinetic staging. The show took off like a bullet train and never stopped. We tried to create a similar feeling in the movie, only this time through camerawork and editing.

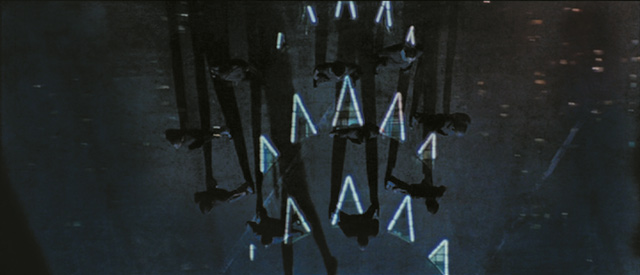

We built the entire car dealership, including this garage, on a vacant lot in South Central Los Angeles. We used exposed trusses for the roof supports, because they created such great angular shadows. But when we designed this overhead shot, we found there wasn’t a large enough opening to get the camera high enough for a straight-down angle on the dancers. Tobias used a 14mm lens to get as wide as possible, but we needed to do some digital work to take out the beams and extend the floor, giving us a clear expanse that we couldn’t achieve practically.

This was actually a happy accident. In the storyboards, we used the Empire State Building for our New York shot, but in post we found a dynamic shot moving around the Chrysler Building. When we cut it in, we were stunned to discover that the dancers in the shot above lined up almost precisely with the crown of the building—an effect we enhanced with a quick match dissolve. A few people have complimented me on carefully crafting a latter-day Busby Berkeley moment, and of course I didn’t correct them.

Musicals are all about making the shift from scene to song as fluid and seamless as possible. To ease the transition from rehearsal to stage performance, an emcee’s voice-over introduces Jimmy Early and the Dreamettes at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, while the dancers form a line in the studio. Then we do a quick dolly move down the row of outstretched fists, and cut to the Apollo where we see a matching shot (number 7) of the same dancers, now in costume.

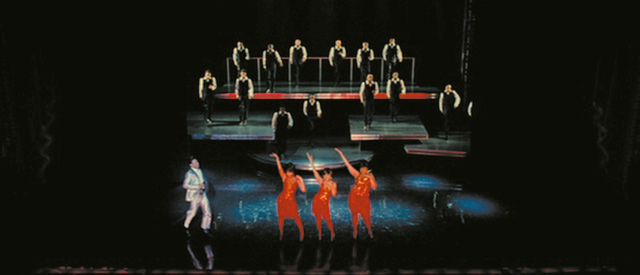

We filmed this on the stage of the Orpheum Theatre in downtown Los Angeles, which stood in for the Apollo. This shot carries us into the song’s final section, our first number with a Broadway-scale set and sophisticated lighting grid. To design the stage numbers (there are over a dozen in the movie), we recruited the legendary theatrical lighting wizards Jules Fisher and Peggy Eisenhauer, who worked closely with Tobias to make sure that what looked right to the human eye translated accurately onto film.

This is one of my favorite shots in the movie. The Dreamettes make their entrance—in red of course—and move toward the light. It’s interesting how much more exciting certain musical moments can be when shot from behind. There’s something about providing a performer’s perspective that makes you feel more connected to the ‘liveness’ of the moment. Here, the combination of red footlights and backlit dresses gives a sense of power and confidence to the Dreamettes, who are enjoying their first taste of success.

The black flats behind the Dreamettes iris out, revealing production designer John Myhre’s stage set, a series of metallic platforms that gently echo the automobile assembly-line culture of 1960s Detroit. We did extensive pre-vis on this sequence, combining storyboards with video footage shot on the rehearsal stage. By the time we were shooting, we had a good idea of which angles worked for specific moments. Because the dancers were moving so fast, what was right for one setup would fall apart in another. So we covered the number with four cameras, gradually moving from left to right across the stage.

This is a Steadicam shot. Jimmy and the women line up, and as he turns we do a countermove with the Steadicam; the camera is, in a sense, dancing with him. Steadicam turned out to be an incredible tool for shooting the numbers. When the operator can get right in there with the performers, there’s so much flexibility that everything tends to feel more immediate. It was a revelation in the cutting room to find how often we’d come back to these Steadicam shots.

Over the course of this two-minute stage number, there are dozens of these cutaways that heighten the energy and excitement of the performance. Here we catch a dancer defying gravity, which matches into a wider shot as he literally comes back to Earth. I found that if we stayed tight too long we lost the spectacle, but the occasional close shot—tambourines, clapping hands—were useful as punctuation points. The lighting towers you see in the background are a specific reference to Robin Wagner’s original stage design, an abstract space dominated by five rotating lighting towers.

John Myhre utilized rising platforms to let us take the sequence to the next level—literally. The two rear platforms start to rise, and, after a series of cuts like the one above (number 11), we pull out to this static wide shot to reveal the effect in full. This shot is held longer than any other in the sequence, to allow the audience to stand back for just a few moments to take in the entire stage.

The song, which started with Curtis laying out his plan for success, now returns to him as it ends. Curtis drives the story of Dreamgirls, but it’s ironic that in a movie about performers, the principal protagonist doesn’t perform. Curtis is always in the wings, or the audience, or a mixing booth. He’s creating a music empire and crashing through huge cultural barriers, but there’s always a sense of solitude about him. Here, his costume reflects the red-and-black motif of the number, but he’s also separate from the performers, and alone.

For the final shot of the sequence we move behind the performers and look straight into the spotlights. To create a smooth transition into the next (non-musical) scene, we took the in-camera flares caused by the spotlights and enhanced them digitally, until the frame is filled with white light. When the light fades, we’re in a recording studio looking at a reel of audiotape, accompanied by Martin Luther King Jr.’s voice on the track. It’s a cinematic device that I hope captures what Bennett achieved on stage—keeping the show in constant motion.