BY ROBERT ABELE

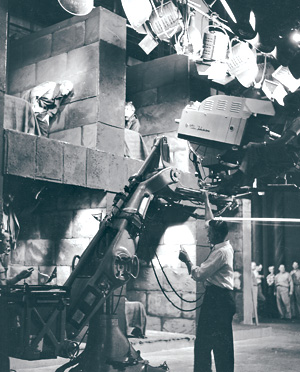

NO LIGHTWEIGHT: Del Mann positions a jumbo TV camera for a live

NO LIGHTWEIGHT: Del Mann positions a jumbo TV camera for a live

performance of "Darkness at Noon" (1955) for Producers’ Showcase.When television was a nascent broadcast medium just beginning to burn up the New York airwaves after World War II, its heat, recalls director Ira Skutch, was not just figurative.

“You’d spend a day in the studio, and they had these old iconoscope tubes which required 800 foot-candles of light, so the studio would get up to 110, 115 degrees,” says Skutch, who worked at NBC in the late ’40s as a floor manager. “One day the art director brought in a bell jar with wax fruit in it for a living room scene, and at the end of the show there was nothing but a puddle of wax at the bottom.”

Joining everyone at a bar for beers afterward was, he jokes, physically necessary. “I used to lose between eight and ten pounds working as a stage manager, so you had to drink that back in.”

Starting around 1946, viewers tuning in to one of the three networks - CBS, NBC or Dumont - were beginning to develop their own unquenchable thirst for the immediacy and excitement of nightly comedy, music and drama from an invention that was just finding its commercial and artistic sea legs. The advent of television - a quickly explosive alternative to the dominance of radio in homes and the communal popularity of moviegoing - would forever change the entertainment landscape. And for the directors who were in at the start, the full-steam-ahead spirit engendered by the novelty of television is still fresh in their minds almost 60 years later.

“We were all learning together, and you could try anything if you wanted to,” recalls Skutch, who has since written and edited a number of books on television’s early days. “It was almost like being back in college, that kind of spirit where everybody does something together.”

Often, that something, recalls director Arthur Penn, was simply steering clear of the cables in the tiny ex-radio studios allotted to television programs. “The question was, how do you block [a scene] so that you don’t cross your cables, because they were big, there were volumes of cables for each camera.”

As Penn points out, “Television directing was not like movies. We had three cameras, generalized lighting that was fairly primitive, and we did the coverage for dramatic emphasis all at one time. There was nothing to look back to.”

The image of the all-knowing director who runs the set with an ironclad grasp of his craft was hard to come by in the infancy of a live medium in which technological kinks were still being worked out. Skutch remembers that game-show director Franklin Heller (What’s My Line?) put it best. “He said, at the beginning, nobody really told anybody else what to do, because nobody knew what to do.”

“It was anything but autocratic,” agrees Penn who also got his behind-the-camera start as a floor manager (also known as stage manager), before graduating in 1948 to become one of a handful of rotating directors on NBC’s now-classic Philco Playhouse. “It was an emerging medium. Every couple of weeks we’d get another little technological advance, like the zoom, or steadily improving sound. It was much more of a tight little community, because the cameramen, the boom operators, the control room personnel, had to be friends of yours. And the actors were delightful, because they were desperate to do something else than the same performance eight times a week on Broadway.”

Although some television directors went straight to the helm from university theater, the usual route was from floor manager up, a job important enough to involve knowing every aspect of the production, yet lowly enough to require endless hours for meager pay. But once you were an employee of the network - no outsiders - promotion to director was sometimes as quick as being asked to fill in for a colleague who was sick.

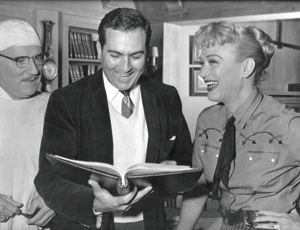

THE GROUND FLOOR: John Rich, here directing "Our Miss Brooks" in

THE GROUND FLOOR: John Rich, here directing "Our Miss Brooks" in

1952, says early TV was great training in the importance of rehearsal.Ultimately, Penn says the qualifications of a TV director back then were twofold: “You had to have the guts of a blind burglar and the coordination of an athlete. It was tough. Quite a few guys ended up sick from it. The pressure of live took some guys down.” Legendary television director John Rich (The Dick Van Dyke Show, All in the Family) recalls that it was great training in the importance of rehearsal and how to make edits, and also - when standing around observing - what not to do. “I used to watch bad directors and learned more from them than good ones. Because if anything went wrong, that was it. You had one shot.”

And yet, the day after the fruits of your labor were broadcast into people’s living rooms - mistakes, moments of grace, and all - the response from the public was instantaneous. “You’d do a show on Sunday night,” adds Rich, “the next day you’d hear people talking about it. Not to you. Just talking about it. They would say, ‘Did you see that last night?’ And of course, it was something like Marty.”

Delbert Mann, who directed Marty for television in 1953 with Rod Steiger as Paddy Chayefsky’s memorably lovelorn Bronx butcher (before remaking it as a theatrical feature with Ernest Borgnine) remembers its initial broadcast impact: “After the first time it was on the air, Steiger said he’d be walking down the streets of New York and people would yell at him, ‘Hey, Marty, we seen you on the show!’”

Because television in its infancy was an amalgam of elements from radio, theater and film - visual, live, performance-oriented and technical - it was originally seen as less than. “People in radio at the beginning had nothing but sort of veiled contempt for you,” says Skutch, who remembers the discouraging words of his wireless colleagues when he moved from the guest relations department to the “backwater” of television. “People I knew would say, ‘It’s not going anywhere.’ But we all had a different feeling, that we were in a whole new field.

The Radio Directors Guild, which had formed in 1942, didn’t take long to admit its television brethren, becoming the Radio & Television Directors Guild in 1947. Film directors, though, cast a suspicious eye on the new medium, and the RTDG and the Screen Directors Guild did not merge until 1960. “An upstart relation” is how Hollywood regarded TV, recalls Rich, who would eventually move to Los Angeles as more series began filming there. “It actually scared a lot of people.” Movie studios were famously concerned about dwindling desire for their product - Jack Warner supposedly forbade his wife to watch television, and banned TVs from Warner Bros. sets - and blamed the rapid popularity of television for keeping audiences away from theaters. “They felt it was crappy and a poor imitation of what they were doing,” says Skutch. “Many of the studios wouldn’t let their stars appear on television. For a long time, movies weren’t released to television.”

If television was seen as the great destroyer then, years later it was VHS and today perhaps online downloads. Skutch believes there’s an important lesson to be learned from the dawn of television. “There’s no standing in the way of progress,” he says. “You better adapt to it fast.”

Once the Young Turks in television established themselves, Hollywood did come calling. “What happened eventually was that the movies bought us, bought the directors, that whole generation,” says Penn, who would go on to direct films like The Miracle Worker and Bonnie and Clyde. “We came out there to make movies, but we made them in a different way.” Penn says what he brought to the big screen from TV directing was audacity. “Not doing the conventional thing, because we had never known any convention. We just knew what the medium of live television was capable of.”