The First Office: Crossroads of the World, an art

The First Office: Crossroads of the World, an art deco office complex in Hollywood, was the site

of the Guild's first headquarters.

This is not a definitive history of the Director's Guild. That would take volumes. What follows in these pages is more a selective history of 70 years, recognition of some of the landmarks and accomplishments along the way. Of course, when any institution turns the ripe old age of 70, there are bound to be a slew of events that have helped define it. No celebration of the DGA would be complete without mention of how the studios (reluctantly) recognized the Guild in 1939, or the merger of the East and West Coast guilds in 1960. But many of the events that helped shape the Guild are not of the headline variety, but an ongoing process, such as the DGA's long-term fight for diversity or its early and lasting support for independent film.

What we hope to reflect in these pages is the range and scope of the Guild's history, some of its achievements, and some of the people who have helped make it successful. What you have in front of you are pieces of the whole, a record of the growth, evolution and humanity of this great institution.

1930's - THE STUDIOS RECOGNIZE THE GUILD

Pioneer: Frank Capra presents D.W. Griffith with the Guild's first Honorary

Pioneer: Frank Capra presents D.W. Griffith with the Guild's first Honorary Life Membership in 1938. (left to right) John Ford, Gild Legal Counsel

Mabel Walker Willebrandt, Rouben Mamoulian, Griffith, Sam Wood,

W.S. Van Dyke, Capra, Leo McCarey and George Marshall.

The Screen Directors Guild (SDG) was gaining momentum in the late 1930s, but the studios still wouldn't recognize it as a bargaining unit. In an interview with Variety on the occasion of the Guild's 50th anniversary, Frank Capra recalled that he changed the studios' attitude with a power play that reverberated throughout Hollywood. At the time, Capra was serving as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Joseph Schenk, then president of 20th Century Fox, was head of the Association of Motion Picture Producers (AMPP), and refused to recognize the SDG as a bargaining agent. To force his hand, Capra threatened not only to resign as Academy president, but also to instigate an industry-wide boycott of the Academy Awards, which was just a week away. The moguls also counted on the awards for their publicity value. At that time, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) was still deciding on the Guild's case. Capra's threat, along with the studios' increasing awareness that the pending decision of the NLRB was going to go against them, resulted in Schenk caving in. The AMPP head told Capra that the studios would meet his demands and the SDG finally received blanket studio recognition on Feb. 18, 1939. As a coincidental bonus, Capra's You Can't Take It With You won Best Picture and he was named Best Director at that year's Academy Awards.

1940s - THE FIRST AWARDS SHOW

First Winners: (left to right) George Stevens receiving

First Winners: (left to right) George Stevens receiving

a plaque for "Outstanding Service," Darryl F. Zanuck

accepting for Anatole Litvak, Guild President George

Marshall, Fred Zinnemann and Joseph Mankiewicz, who won the Guild's first annual Achievement Award.

"This has to be a family affair, free from prejudice and unhampered by outside influence. You yourselves are to be the judges and the jury because no person is better qualified to pass upon the creative ability of the director than the directors themselves." So said Screen Directors Guild President George Marshall as he announced in August 1948 that the Guild would hold its own awards show. The first Screen Directors Guild Best Director Award was presented to Joseph Mankiewicz for A Letter to Three Wives in May 1949. For the first year or two, the honor was bestowed on a quarterly basis, with the recipient of the most votes - Mankiewicz in that first year - receiving an annual award at a ceremony. At that time, the Motion Picture Academy wanted the guilds to abandon their awards in lieu of submitting nominees to the Academy Awards. "But no, everybody wanted their own and that was unacceptable," said longtime SDG and DGA President George Sidney, who chaired the committee that launched the SDG Awards. The quarterly awards were soon dropped, but bigger changes were looming. The advent of television provided a particular challenge. "We didn't know what to do about TV because a lot of members didn't have television," according to Sidney. "'I'm going to spend $800 to watch wrestling?' So when we would nominate different TV shows, the members would come to the Directors Guild and watch them because a lot of people didn't have televisions. As they left the theater, they voted."

1940s - DIRECTORS IN THE SERVICE

In the Army Now: Colonel Frank Capra and Commander

In the Army Now: Colonel Frank Capra and Commander John Ford helping the war effort in 1941.

To Frank Capra, it was a film that "fired no gun, dropped no bombs. But as a psychological weapon aimed at destroying the will to resist, it was just as lethal." That propaganda film, Triumph of the Will, by German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, chronicled the Nazi Party's rise and inspired Capra to respond in similarly forceful fashion on behalf of the U.S. war effort during World War II. Capra was not alone, as several prominent Hollywood directors, including John Ford, William Wyler, George Stevens and John Huston, joined him in making films and documentaries on behalf of the U.S. Army Signals Corps. Capra's series of seven films, Why We Fight, motivated the troops and rallied those on the home front, and at the same time helped revolutionize the art of documentary filmmaking. Capra cleverly used the Axis Powers' propaganda footage against them by cutting it into his films, with a decidedly opposite message. Ford, already a film legend, was equally eager to enlist his skills in the war effort and even sustained battlefield injuries during production of The Battle of Midway, which won an Oscar for best documentary in 1943. His film of the Pearl Harbor invasion, December 7th, won for best short subject documentary the following year. Wyler also spent much of the war documenting battles, including bombing raids in France and Germany in Memphis Belle. Let There Be Light, Huston's final entry in a trilogy of government films, chronicled the treatment and rehabilitation of U.S. soldiers in a psychiatric hospital, and is still considered one of the most forceful anti-war films.

1940s - THE DGA FOUNDATION

The DGA Foundation has fulfilled its mission of handling hardship cases with compassion and discretion since its inception on June 7, 1945 as the DGA Educational and Benevolent Foundation. "Its purpose was to help a person borrow a few dollars to help out between jobs, to help someone who couldn't pay his telephone bill, or to help a guy who didn't have a decent set of clothes to go to an interview," said former DGA National Executive Secretary Joe Youngerman. The foundation was conceived by the Guild's legal counsel, Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who believed it should operate independently of the Guild to ensure the anonymity of those receiving assistance. Director Leo McCarey got things going with a $25,000 donation from his earnings on two hit features, Going My Way and The Bells of St. Mary's. Under the plan, members could receive no-interest, short-term loans. The foundation's founding officers were McCarey, Joseph Mankiewicz, Frank Capra, Tay Garnett and John Farrow. Through the years, the foundation has been chaired by McCarey (1945-49), Mankiewicz (1949-50), Capra (1950-52), Robert Butler (1952-79), Delbert Mann (1979-1983), Howard W. Koch (1983-2001), Mann (2001-2004), Jack Shea (2004-2005) and John Rich (2005-present). From its inception, the foundation has remained especially supportive of the Motion Picture and Television Fund, which has included gifts to the Motion Picture Country Home and Hospital, and funds to build more hospital rooms, expand assisted-living facilities and support the MPTV Fund Health Care Center. Since 2000, the foundation has also been the sole underwriter for conservation and preservation of the DGA-Motion Picture Industry Conservation Collection at UCLA. This collection maintains more than 800 new prints of feature films directed by DGA members, ensuring that their work is preserved for future generations. But the primary mission of the foundation continues to be in assisting members in times of financial crisis. Donations from DGA members continue to sustain the foundation, along with proceeds from the annual Howard W. Koch Memorial DGA Golf and Tennis Tournaments.

The DGA Foundation has fulfilled its mission of handling hardship cases with compassion and discretion since its inception on June 7, 1945 as the DGA Educational and Benevolent Foundation. "Its purpose was to help a person borrow a few dollars to help out between jobs, to help someone who couldn't pay his telephone bill, or to help a guy who didn't have a decent set of clothes to go to an interview," said former DGA National Executive Secretary Joe Youngerman. The foundation was conceived by the Guild's legal counsel, Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who believed it should operate independently of the Guild to ensure the anonymity of those receiving assistance. Director Leo McCarey got things going with a $25,000 donation from his earnings on two hit features, Going My Way and The Bells of St. Mary's. Under the plan, members could receive no-interest, short-term loans. The foundation's founding officers were McCarey, Joseph Mankiewicz, Frank Capra, Tay Garnett and John Farrow. Through the years, the foundation has been chaired by McCarey (1945-49), Mankiewicz (1949-50), Capra (1950-52), Robert Butler (1952-79), Delbert Mann (1979-1983), Howard W. Koch (1983-2001), Mann (2001-2004), Jack Shea (2004-2005) and John Rich (2005-present). From its inception, the foundation has remained especially supportive of the Motion Picture and Television Fund, which has included gifts to the Motion Picture Country Home and Hospital, and funds to build more hospital rooms, expand assisted-living facilities and support the MPTV Fund Health Care Center. Since 2000, the foundation has also been the sole underwriter for conservation and preservation of the DGA-Motion Picture Industry Conservation Collection at UCLA. This collection maintains more than 800 new prints of feature films directed by DGA members, ensuring that their work is preserved for future generations. But the primary mission of the foundation continues to be in assisting members in times of financial crisis. Donations from DGA members continue to sustain the foundation, along with proceeds from the annual Howard W. Koch Memorial DGA Golf and Tennis Tournaments.

1950s - ESTABLISHING PENSION AND HEALTH

The DGA-Producer Pension Plan was born out of the Hollywood labor strife of the late 1950s over the reuse of films on television. The Screen Actors and Writers Guild were on strike over the residuals issue, and the DGA was preparing to negotiate, when Republic Pictures broke a 12-year moratorium on exhibiting films on television without negotiating a residual payment to the Guilds. Sensing that other studios could follow suit, DGA National Executive Secretary Joe Youngerman came up with an ingenious solution. He proposed giving up residual rights to films from the past 12 years, from 1948 until the present, valued at $100 million, in a trade-off: "We'll give back 12 years of film in exchange for a new pension plan for directors and their assistants."

George Stevens, Frank Capra, George Sidney, John Rich and Youngerman pitched the idea to the presidents of the major studios, who accepted it. Before that, directors had been covered by the Motion Picture Industry Plan, but their benefits were based only on the hours they spent on the set, not the time spent in pre- or post-production. The new pension plans were a major achievement for the Guild and showed great foresight, finally giving members a meaningful retirement plan.

The DGA-Producer Health Plan was added in 1969, filling another crucial gap in the benefits available to Guild members. As it was structured, the pension plan benefits all members of the directorial team. A share of residuals also goes to the plans. The plans are a separate trust administered independently from the Guild and overseen by trustees split equally between representatives of the Guild and the signatory companies.

As Sheldon Leonard recalled, "Getting the pension plan started was the biggest obstacle. After that, it was a downhill run. In order to get it started, we had to get the employers in this industry to agree to make a very substantial contribution. Once started, however, we were able to keep pace with the growth of the Guild."

And grow it has. The plans have combined assets of about $2.1 billion and contributions from employers rose to nearly $140 million last year. From this, the plans have been able to pay out more than $1.2 billion over the past 10 years, including about $159 million in 2005, or about $13.25 million per month to their participants.

1950s - Breaking Ground

Digging In: (left) Guild President George Sidney breaking ground for the new

Digging In: (left) Guild President George Sidney breaking ground for the new

headquarters at 7950 Sunset Blvd. in 1954. Also pictured are Paul Guilfoyle,

Milton Bren, Clarence Brown, Fred Guiol, William Seiter, Reginald LeBorg,

George Stevens, Leslie Selander, Claude Binyon, Joseph Mankiewicz, Stuart

Heisler, Frank Borzage, Norman McLeod, Rouben Mamoulian, George Marshall,

Leo McCarey, Rudolph Mate, Alfred Santell, Louis B. Mayer and Howard Koch.

1960s - Assistant Director Training Program

"In our program, the desire is to give, in effect, a course that endeavors to equip the man with all the basic knowledge of the job, the intricacies of all the technical aspects. In this way the new assistant will be better able to serve the director in all his creative needs, and in this way better serve the producing company," said DGA President George Sidney in 1965 about the formation of the Assistant Director Training Program. He was confident that the ADTP would prepare the next generation of workers, and the past four decades have proven him right. The program recently marked its 40th anniversary as a partnership between the Guild and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. It has graduated more than 500 trainees from the separately administered programs on the West Coast and East Coast. Trainees undergo 400 days of on-the-job work experience, rotating between several film and television projects for a variety of experience. The ADTP has made it a priority to include a significant percentage of women and minorities. "I'll always be grateful to the Guild and the training program for reaching across the country and providing me a unique opportunity and a wonderful career I wouldn't have had otherwise," said Herb Adelman, a 1977 graduate of the program who later served as a trustee on the program for 10 years.

1960s - The Merger of the Guilds

"Finally, when we met with them and sat with them, drank with them, we found out that they weren't so terrible," former Screen Directors Guild, and later DGA President George Sidney recalled of early efforts to merge various types of directors guilds into one organization. Suspicion was mutual between the film directors in the Los Angeles-based Screen Directors Guild and those working in live television through the New York-based Radio and Television Directors Guild. "Each side felt that the other was going to try to swallow it up, and impose its will, but in 1960 we became one union," according to Joe Youngerman, SDG's executive secretary at the time of the merger.

A merger was first discussed in 1956, but it took two years for Youngerman and his counterpart at RTDG, Newman "Nicky" Burnett, to bring together committees from both sides. Sidney would later half-joke that "we both had something in common - we all hated the producers," but there were many reasons to combine. For one, there was a large number of directors who belonged to both guilds, paying double dues and giving production companies the opportunity to negotiate two different deals. The RTDG, founded in 1942 as the Radio Directors Guild - later adding television directors by 1948 - was in tough financial straits as opposed to the SDG. And directors realized that, despite the different mediums, they shared much in terms of craft and working conditions. They were, as John Rich, who belonged to both guilds, recalled, "directors of people instead of directors of different kinds of equipment."

Still, the early negotiations took place in secret. The leaders did not want to startle the paid staff who might lose their job in a merger, and it was agreed that inactive RTDG members would not be brought into the new Guild or allowed to reactivate, which generated resentment for years after the merger. Several New York RTDG members were instrumental in easing the transition, including then-RDTG National President Michael Kane, George Schaefer, Tom Donovan and Ted Corday. Jack Shea, President of RTDG's Hollywood local, Sidney and Rich also played leadership roles in the merger and subsequent DGA, whose first president would be Frank Capra.

The merger, which took place on Jan. 1, 1960, nearly collapsed early on due to conflicts between the councils on the two coasts, each of which contained both directors and assistants in all areas. Separating the directors and assistants into separate councils eased much of the East-West friction, Shaefer later recalled. "Growth is the bellwether of any organization, and our Directors Guild knew it had to grow," Sidney recalled.

Assistant directors covered by IATSE Local 161 in New York were the next to join the new DGA in 1963, thanks to then-IATSE President Richard Walsh. "We proved to Dick Walsh that we could do a much better job, and he, not wanting to just keep numbers in the IA, but wanting to do the best for his membership, surrendered and gave us the members of 161," according to Sidney.

Unit production managers merged with the DGA in 1964, and in 1965 the Guild added the members of the Screen Directors International Guild, a New York-based group whose members largely directed TV commercials and documentary films.

Reflecting on the various mergers that created the DGA, Schaefer said, "It seems to me that directing is such a difficult job that the miracle of making a show come together should not be limited by geography or by arbitrary restrictions. A director should be a director any place in the country - or the world, for that matter."

1960s - RESIDUALS ARRIVE

Compensating artists for the use and reuse of their work was first envisioned in Europe before the 20th century and has been a battleground ever since. But unlike their European peers who work in an Authors Rights system, which gives them rights to control and have remuneration for the reuse of their art, directors in America's Work for Hire system had to rely on collective bargaining to secure residuals.

Residuals are one of the most significant benefits available to members of the DGA, allowing them to benefit financially from a work years after its release. This provides a safety net for lean years throughout a career and a source of income that is supplemental to some members and vital to others. Residuals are also the fundamental source of revenue for the DGA Basic Pension Plan.

The issue of residuals has arisen with each new technological advance, beginning with the advent of radio and coming to a head with television. The DGA and other Hollywood guilds negotiated residuals for domestic reuse of TV programs in the 1950s but ran into resistance when it came to getting paid for feature films shown on the new medium. The issue was so contentious that a 12-year moratorium on exhibiting films on TV was declared in 1948. A residual formula for the reuse of films on free TV was established in 1961, and payment for the foreign reuse of TV programs came in 1968. The reuse of films on pay television and videocassettes, the "supplemental markets," were first addressed in 1971. Along the way, various other forms of reuse were covered, such as made-for-pay TV, made-for cable, and Internet uses.

Direct residual payments benefit not only directors, but also go to below-the-line members of the Guild for the reuse of films in supplemental markets and for programs made for pay cable television. In addition, residuals generate 60% of the revenue received by the Basic Pension Plan.

The contracts negotiated by the DGA with the major studios and networks have generated stunning rates of residual growth. In the last decade alone, total collected residuals have grown from $109.2 million in 1995 to $246.5 million in 2005. Collecting these residuals involves the coordination of several DGA departments, beginning with Signatories/Report Compliance, which works to make sure a company will pay what's due for years to come. The Residuals Department processes the money received from production companies and monitors industry compliance with the reuse provisions of DGA contracts, which are enforced by the Legal Department.

1960s - Director's Cut Established

From the inception of the DGA, one of the leading goals was to establish a right to a director's cut, but it took over 20 years to achieve this early objective. Director Elliot Silverstein experienced the need for Guild protection firsthand in 1963 after directing an episode of The Twilight Zone, ironically titled "The Obsolete Man." "Its editor refused to cut it the way I wanted it cut," recalled Silverstein. "The only [post-production] right we had in the early '60s was to make suggestions for improvements in the rough cut to the associate producer." Silverstein found that other directors were having similar problems, so he and a group of 24 directors met with DGA National Executive Secretary Joe Youngerman to see what could be done. Those sessions gave birth to the Bill of Creative Rights, which included such landmarks as the establishment of the director's cut, as well as provisions for the director to receive final credit on the main titles. As this represented a substantive change in the way they had always viewed the post-production process, the studios, of course, resisted. To overcome opposition, the Guild submitted a list of 12 directors and said if a director held up post-production, the DGA, at its own expense, would fly in one of those directors to finish the work. The Bill of Creative Rights has since grown into the Creative Rights Handbook, which summarizes the rights of DGA members.

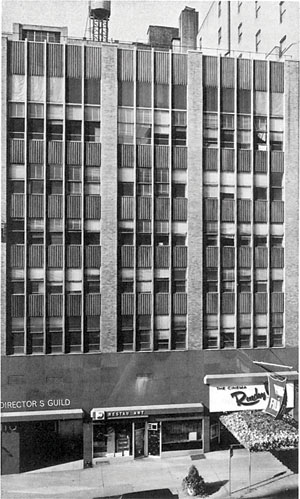

1960s - East Coasting

New York, New York: Two-term President George Sidney was

New York, New York: Two-term President George Sidney was instrumental in acquiring the building on West 57th Street that

would become the DGA headquarters for the East Coast.

1970s - 30 Years of Special Projects

One morning, almost 15 years ago, several dozen members gathered at the Directors Guild for a breakfast presented by the Special Projects Committee that featured Michael Mann in a discussion of pre-production issues. With the recent release of his latest film, The Last of the Mohicans, Mann brought his enthusiasm for the picture - along with a musket used by Daniel Day-Lewis in the film. The musket became the focus of a lively demonstration of the director's rehearsal process and how he helped the actor to physically inhabit his character.

Three Cheers: The Special Projects Committee celebrates Robert

Three Cheers: The Special Projects Committee celebrates Robert Wise's 86th birthday in 2000.

Not the usual fare over bagels and coffee, perhaps, but as one of the many offerings of the Special Projects Committee, it was definitely part of what puts the "special" in Special Projects. For 30 years, the committee has been providing Guild members with unique opportunities like this to get to know individual directors and their work, and to learn more about the craft.

The first endeavor of its kind among entertainment guilds, the Special Projects Committee was inspired by a three-page letter written to the DGA Western Directors Council in 1975 by Elia Kazan, who believed that a Guild "...has the obligation to inspire its every member to better work... pass on its traditions, see that they do not die, that the lessons of experience are not ignored, that achievement builds on achievement."

Accordingly, Guild President Robert Aldrich, who was president at the time, appointed a committee, chaired by the venerable Robert Wise, to explore the matter further. On June 12, 1976, a recommendation to establish a special projects program was unanimously resolved by the DGA National Board.

Celebrations: Ray Bradbury gave an inspiring keynote

Celebrations: Ray Bradbury gave an inspiring keynote address at Digital Day in 2005.

By all accounts, there couldn't have been a better choice for chairman than Wise, who selected the committee's sole staff member, David Shepard, and wielded his considerable influence to get things accomplished. He appointed an operations subcommittee, consisting of Noel Black, Lamont Johnson and Francine Parker. Wise held the post for nearly a quarter-century, retiring in December 2000. Ten years ago, he noted in the DGA Magazine that when it came to his service to the Guild, he was most proud of his Special Projects involvement.

The committee took its mandate from a phrase in Kazan's letter, "to collect, preserve and share" the directorial experience, says Shepard, who worked with the committee for more than 10 years. "Our original work included oral histories and media educators' workshops," Shepard says. The oral histories came about because "you had to do it," declares Parker. "It was imperative - these were people who did very valuable work. They were directors and assistant directors who cared about the Guild, and who were pioneers."

The oral histories have given way to the Visual History Program. The Special Projects Committee also continues to organize tributes, incorporating the screening of a director's film with remarks from creative collaborators. One of the earliest Special Projects events saluted John Cromwell, with George Cukor as panel moderator.

For several years, starting with a session with Howard Hawks in Laguna Beach in 1977, the Committee presented up-close-and-personal weekends spotlighting the work of a single director. The retreats have evolved into one-day intensives held at the DGA headquarters. Last September, Garry Marshall, Jim Burrows, Donald Petrie, Betty Thomas and others talked about directing comedy.

In 2000, Wise was succeeded as chairman by committee member Jeremy Kagan. Kagan had already distinguished himself by initiating events such as Directors Breakfasts and the annual Meet the Nominees Symposia, which present discussions with the nominees for the annual DGA Awards. In developing the symposia, Kagan's goal was "to provide more opportunities for Guild members to be in conversation with each other."

Four DGA staffers, led by Special Projects Executive Gina Blumenfeld, now work on ongoing committee programs. Current offerings include new technology seminars and workshops, as well as the Global Cinema Screening Series, co-chaired by Victoria Hochberg and Chuck Workman.

Celebrations: John Huston (right) and Barbara Streisand at a dinner for

Celebrations: John Huston (right) and Barbara Streisand at a dinner for Akira Kurosawa who received the Guild's Golden Jubilee Award in 1986.

The annual Digital Day event provides members with presentations and hands-on demonstrations of the latest technological advances. In July 2006, more than 500 members and their guests packed the three DGA theaters and grand lobby in Los Angeles for the fourth Digital Day event and got to review a host of new technology.

"I've always been interested in cutting-edge technology and its applications," notes Digital Day subcommittee chair Randal Kleiser. "What formats should a director consider? What's the cheapest and best equipment for low-budget projects? In general, what should members know about changes in their craft?"

As the needs of members continue to evolve, so has the work of the Special Projects Committee. As Kagan notes, "When you stop learning, you stop living."

—Libby Slate

DGA In Print

Action! Magazine first published in October 1966 with a broad mix of profiles, interviews, features and news to serve as the "Voice of the Guild" and explore all aspects of DGA membership.

DGA News was first published in July 1977 as a newsletter dedicated to chronicling the Guild's internal affairs, and grew over 20 years to become a glossy with a mix of news and craft.

DGA News was relaunched in January 1996 as DGA Magazine, a bimonthly publication rich with features, photo spreads and profiles, while taking a deeper look at Guild history and current events.

DGA Monthly launched in November 2004 in response to member requests for more timely and expanded coverage of Guild news, departments and events in a single publication.

DGA Quarterly , the successor to DGA Magazine, debuted in the fall of 2005 as a journal exclusively devoted to exploring the craft and history of directors and their teams.

1980s - The Guild's New Home

Construction Crew: (from left) President Gil Cates and past presidents

George Sidney, George Schaefer, Delbert Mann and Robert Wise

break ground for new headquarters in April 1987.

"The piece of land was just sitting there. I refused to convene the board meeting unless they let me buy it," former DGA President George Sidney recalled of his efforts to purchase property across the street from the Guild's first permanent headquarters on Sunset Boulevard and Hayworth Street. Sidney wanted to build a 20-story tower to provide offices not only for the Guild but for directors and post-production houses. Those plans faded, but not the dream of creating a signature building for the DGA. The idea was finally implemented in the mid-'80s under the leadership of then-DGA President Gil Cates. The vision was for an "advanced and timeless architectural statement." Groundbreaking took place on April 11, 1987 with Sheldon Leonard, the project's shepherd and building committee chair, calling it a "monument to our craft and to the dedication of the members who made it possible." The six-story structure took about 18 months to complete and incorporated generous amounts of carnelian granite from Minnesota, copper-colored glass from Belgium and red granite from Texas. "It's a beautiful building. It will definitely be a landmark in the area," Sidney commented as the Guild prepared to move into its new home.

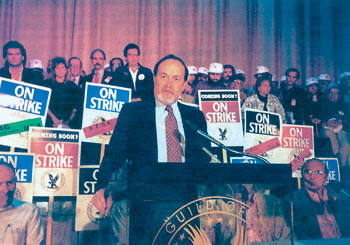

1980s - The Five-Minute Strike

Back to Work: Gil Cates helped orchestrate the Guild's only strike in 1987,

Back to Work: Gil Cates helped orchestrate the Guild's only strike in 1987, but it lasted only five minuts on the West Coast before it was settled.

"This is what we do for a living - if anybody should be able to organize and run this kind of operation, we should," said Bob Butler, who headed the Strike Committee during DGA's first and only industry strike. The work stoppage on July 14, 1987, lasted just five minutes on the West Coast, but took months of planning. Butler, a veteran TV director, was recruited by Guild President Gil Cates to lead the efforts in Los Angeles. Separate plans were made in the DGA's New York offices under local leaders, while committees on both coasts handled the details of phones, computers, first aid, site coordination, maps and permits, disciplinary actions and strikers' support aid. Plans called for having nearly 5,000 members, led by 200 picket captains, taking up positions outside dozens of locations throughout Hollywood. Tensions were stoked by AMPTP's proposed rollbacks which were withdrawn minutes after the strike began in Los Angeles, and three hours and five minutes after it got underway on the East Coast.

1980s - The Road to Diversity

Any discussion of diversity issues at the DGA leads inevitably to the so-called "Danish Debacle" of 1981. For more than a year, the DGA had tried, unsuccessfully, to get executives at the studios and production companies to address their dismal record on hiring women directors. At the time, National Executive Director Michael Franklin was frustrated that industry leaders weren't receptive to change, so he tried one last tactic - a breakfast where the two sides would try to reach consensus. But no executives showed up to eat the catered Danish pastries.

It sounds like a funny piece of Guild trivia, but the pastries became a symbol for the industry's disregard for diversity issues. Since then the Guild has not allowed Hollywood to simply ignore the inclusion problem.

Crouching Tiger: Members of the Asian-Amerian Committee

Crouching Tiger: Members of the Asian-Amerian Committee welcome Ang Lee (center) in Dec. 2005.

The impetus for a Guild diversity plan began in 1979 with a group of award-winning women directors who noticed they were falling behind their male friends. "A group of us who had done pretty well looked around and realized that all of the men we had started with were moving forward and we weren't," says director Victoria Hochberg. Hochberg and her colleagues - Susan Bay, Nell Cox, Joelle Dobrow, Dolores Ferraro and Lynne Littman - formed the Women's Steering Committee and spent a year analyzing DGA deal memos, then quantified their findings at a June 1980 press conference.

They revealed that between 1941 and 1980, only one-half of one percent of the available work in film and television had gone to women directors. Their finding inspired an ad hoc Affirmative Action Committee to lobby on behalf of the women and minority members. Around the same time, the Ethnic Minority Committee was founded, largely due to the efforts of Wendell J. Franklin, the first African-American member of the DGA, and fellow African-American directors Ivan Dixon, William Crain and Reuben Watt. After the Danish Debacle, the Guild's leadership realized in order for there to be progress, the DGA would have to become aggressive in its advocacy.

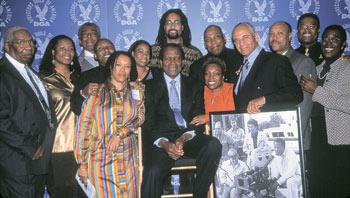

Seated: The African-American Steering Committee presents Sidney

Seated: The African-American Steering Committee presents Sidney Poitier (center) with a director's chair in Feb. 2001.

And it did. In 1983 the Guild filed suit against Warner Bros. and Columbia Pictures charging discrimination. The legal action, however, came to an end in 1985 when a controversial district court ruling stated that the Guild could not participate in the class action suit. Nevertheless, the suit had sent a message that seemed to produce results in the 1987 BA/FLTTA negotiations. By 1995 women directors accounted for 16 percent of total days worked by Guild members. And to commemorate its 60th anniversary, the DGA designated 1996 as its Year of Diversity. In 1997, the Guild held its first Summit on Diversity and inaugurated the DGA Diversity Award to honor consistent hiring of women and minorities. The industry had been jolted to an awareness of the Guild's talented but underemployed members.

In recent years the committees' efforts toward improving diversity have continued. In 1990, six Latino directors - Luis Valdez, Sylvia Morales, Edward James Olmos, Frank Zúñiga, José Luis Ruiz and Jesús Treviño - proposed the formation of the Latino Committee, which was ratified by the National Board in February 1991. "We resolved that we were going to get our names going in the Hollywood community after years and years of not being on the radar screen," says Treviño. The Ethnic Minority Committee became the African-American Steering Committee in 1994, co-chaired by Roy Campanella II, Deirdre Dix and Kevin Hooks. Within the last decade the Asian-American Committee was organized. And more recently, in New York, the Ethnic Diversity Steering Committee was established.

Screening: The Latino Commitee sponsors a showing of

Screening: The Latino Commitee sponsors a showing of Andy Garcia's film, The Lost City, in March 2006.

In addition to monthly meetings, the committees sponsor mixers, seminars and other structured events. "We are very proactive," says Liz Ryan, co-chair of the Women's Steering Committee. "We've consciously taken the tact to create events that expose members to the latest opportunities."

Since its inception, the African-American Committee has organized numerous seminars, panel discussions and tributes to pioneering African-American directors such as Gordon Parks, Melvin Van Peebles and Debbie Allen. "Moving Forward: A Catalyst for Change," a November 1994 panel discussion, inspired the creation of the DGA-Disney Directors Training Program. In 2006, the committee successfully lobbied the NAACP to honor African-American directors in three categories at its annual Image Awards.

The committees have also helped the Guild to recognize and support breakthrough work. "I think we were a significant factor in Ang Lee winning the DGA Award for Crouching Tiger," says Sandy Tung, co-chair of the Asian-American Committee. "We premiered that film at the DGA [in 2000]. I think it brought to the other directors in our Guild awareness that this is a significant film by a significant director."

In 1991, the Latino Committee created and mailed out its own directory of members, which continues today as the annual DGA Women and Ethnic Minority Contact List. A DVD sampler of emerging directors' work - a "you-ought-to-know" showcase of talent - is also a member-generated innovation of the Latino Committee. "The committee tries to get members to come up with ideas of how they can get people working in the business," says Latino Committee Co-Chair Jay Torres.

Inspired By: The Ethnic Diversity Steering Committee presents

Inspired By: The Ethnic Diversity Steering Committee presents a Tribute to Gordon Parks in Oct. 2006.

There is also growing emphasis on maintaining and improving skills, with the committees offering technology workshops on new equipment and techniques. "We're looking at making sure our members are aware of what the technology is and how they could possibly find employment within that technology," says Millicent Shelton, co-chair of the African-American Committee. On occasion the committees work together and have co-hosted the DGA Student Film Awards since its inception in 1995.

Judging strictly by the numbers, the challenge of creating diversity is still a work in progress. Since 1983 the DGA has publicly - and loudly - reported women and minority hiring statistics. DGA President Michael Apted has made diversity issues a major item on his agenda. Under his leadership, the Guild initiated a hiring program for women and minorities in conjunction with ABC/Touchstone and is working on a similar program with the other studios and networks.

Changing Times: Founder of the Women's Sterring Committee in the early '80s.

Changing Times: Founder of the Women's Sterring Committee in the early '80s.

"The day he was elected, he made it really clear our issues were his issues and from the jump has made good on that promise," says African-American Steering Committee Co-Chair LeVar Burton. "He has made minority issues a part of his conversations on the studio level and the network level." Burton points out that minorities are also moving into general leadership roles. And in 2002, Martha Coolidge was elected the Guild's first woman president.

There's still a lot of work to do. As Rolando Hudson, co-chair of the Ethnic Diversity Steering Committee, points out, "We're a guild - we can't force the studios to hire people, we can just suggest." But the DGA makes sure Hollywood doesn't ignore its women and minority members. "We don't have to achieve the world," says Henry Chan, co-founder of the Asian-American Committee. "But every little step helps."

-Desa Philadelphia

1990s - Support for Indie Films

Indie Voice: (left to right) Dan Algrant, Brad Anderson,

Indie Voice: (left to right) Dan Algrant, Brad Anderson, Steven Soderbergh, Mary Harron and Tom DiCillo.

(Credit: Scott Gries/Getty Images)

"There were three main reasons why the DGA developed low-budget agreements," says Western Executive Director G. Bryan Unger. "In the 1970s and early '80s several directors who had started in the independent low-budget world joined the Guild as a result of doing bigger, usually studio, projects. Those directors then continued to be offered independently financed (and generally lower budgeted) films, or they returned to developing their own personal films, more in the style and budget of their earlier work. Without a low-budget agreement contract that could accommodate the salary structures necessary for those pictures, directors were faced with either turning down the independently financed projects or resigning from the Guild. So the DGA got to work on solving that issue.

The second reason was to welcome independent directors like Spike Lee and John Sayles who mainly work outside of the studio system without DGA protection. The third reason was to increase employment and benefits for Guild production managers and assistant directors, who were not being used on lower budget films."

"I don't think it's overreaching to say we pioneered the concept of low-budget agreements, which have nurtured the production of independent films and helped our members do them flexibly under a Guild contract," says Assistant Executive Director Jon Larson. "It's led to similar agreements being promulgated by our sister guilds."

A whole new way of doing independent films, in fact, was made possible by the existence of the agreements. "The low-budget agreement was crucial for me being able to form InDigEnt in 1999," says IDC member Gary Winick of his New York-based production company. "I was going to get experienced, DGA directors to do these films for $400,000, and I had to make sure I could get deals with Sound One and Kodak. The DGA was the first to step up and see the value of their filmmakers doing films like this and getting gross participation. Once the DGA was in place, I was able to get other deals."

Since its inception in 1984, the agreement has been multitiered; in 1992 it changed its three tiers to allow for individual negotiations under $1.8 million, and then expanded to a four-tiered structure in 1998. Today's agreement, continually reviewed to keep up with trends and the ever changing effects of new technologies, covers films produced for up to $7 million. The agreement has four main tiers, with the bottom and top tiers divided into two sub-tiers, for purposes of determining the AD/UPM scale rates. "There's an open dialogue with the producers so everyone continues to view it as a win-win," says Larson. "The DGA is not just an organization for directors who do big studio films. We're much richer than that."

The Independent Directors Committee was created in Los Angeles in 1998, spearheaded by filmmakers like Michael Apted, who became the first IDC committee chair, Steven Soderbergh, Penelope Spheeris, Stephen Gyllenhaal and George Hickenlooper, to continue to address the needs of Guild members who work in the independent arena. One popular event is the Under the Influence screening series, where a younger filmmaker examines a classic film with its groundbreaking and indie-inspiring director such as the recent pairing of Warren Beatty and Bennett Miller. In 2002, a New York committee was created with the same mission of advising the Guild and organizing events for independent filmmakers.

"I think the committees have been valuable in bringing in young filmmakers and being flexible with the contracts," says director and the IDC West Coast Chairman Stephen Gyllenhaal. "You can make a film for nothing and still be a DGA film now, which allows neophyte filmmakers to begin working with Guild 1st ADs and production managers on tiny films. It makes those films better, which makes the filmmakers more powerful, which allows them to connect with more money and the studios, if they wish.

"The business has been experiencing a profound change," continues Gyllenhaal. "Everything from iPod to video projection systems to the Web is becoming a primary distribution system. Everyone has grown aware that the independent world has been rising in importance. I think the next series of negotiations with the studios and networks, with the shift away from DVDs to downloading systems, will make the IDC and DGA skew more toward an independent perspective. Thinking independently, which is where we've been able to move the Guild, will allow us to keep serious financial, political, but most importantly, creative power.

By all accounts, flexibility has been, and will continue to be, the key to surviving as an independent. "As new production techniques come into use, the roles of the director and the DGA team are also evolving, more so now than in the first 70 years of the DGA's existence," explains Unger. "Often we see the cutting-edge changes happen in the areas outside of the mainstream studio system, so we have to be vigilant to protect against erosion of the creative rights, stature and authority of the director and, at the same time, we have to be adaptable to change. The challenge is seeing the forest while running at full speed through the trees."

—Rob Feld

1990s - Runaway Production

Leaders of the PAC: National Executive Director Jay D. Roth (right) and

Leaders of the PAC: National Executive Director Jay D. Roth (right) and PAC co-chairs Paris Barclay (left) and Taylor Hackford (2nd from right)

welcome Congressman Howard L. Berman (D-CA).

"This will be a hard, tough fight. It will require the unity of us all because it affects us all. None of you should think that this will not ultimately affect you. If we do not make a stand now, to regain those jobs already lost, we will all suffer the consequences." Jack Shea, then-DGA president, delivered this tough message to the DGA's annual membership meeting in 1999. He was announcing a historic study commissioned by the DGA and SAG to gauge the actual economic impact of runaway production. After decades of anecdotal evidence on runaway production, The Monitor Report estimated that it had $10.3 billion in total economic impact on the U.S. in 1998 alone, not to mention the loss of 60,000 jobs in the three years preceding the report.

DGA leaders had already made runaway production the Guild's top legislative priority, and The Monitor Report provided the data to backup the Guild's position. Two prominent Washington lobbying firms were retained and the DGA became an instrumental force in the Runaway Production Alliance, which included other guilds and unions, studios, independent and commercial producers, the post-production community and all the U.S. film commissions. While the Guild was working in Washington for over four years, efforts were also being made in Los Angeles through the DGA PAC Leadership Council, which met with more than 29 key members of Congress to explain the situation in very concrete and personal terms. The culmination of this effort was the inclusion of a new provision in the 2004 JOBS Act. This law included tax incentives for qualified productions and marked the first time that runaway production had been acknowledged as a major problem at the federal level. Examining the impact of this provision is going to be part of the ongoing efforts of the DGA in this area.

The Guild has always pursued a multi-tiered approach to runaway production, so while supporting the federal incentive, the DGA also encouraged the efforts of states to enact their own incentives to further counter the impact of foreign incentives and subsidies. To date, 30 states have enacted their own incentives. However, California is not one of them, despite guild and industry efforts. On the local level, the DGA supported the creation of New York City's incentive program, which has proven highly successful, and Los Angeles' efforts to ease business tax and regulatory burdens.

"The DGA has taken a leadership role on behalf of the entire industry - and we are now seeing the fruits of our labors," says DGA 3rd Vice President and PAC Chair Taylor Hackford, who co-chairs the PAC Leadership Council with Paris Barclay. "The DGA and the Leadership Council have been working tirelessly to capture the attention of lawmakers in Washington and are tremendously proud of the inroads we have made."

2000s - Protecting the Possessory Credit

Well before there was a Directors Guild of America, directors were accustomed to seeking and receiving a possessory credit on their feature films. The first director to take a possessory credit is believed to be D.W. Griffith for Birth of a Nation in 1915. Other directors later made the practice commonplace, including Frank Capra, George Stevens, King Vidor and Alfred Hitchcock. In each case, the credit was negotiated by the individual director, a practice the DGA has subsequently maintained every director involved in a motion picture is entitled to.

Despite that longstanding principle, the possessory credit has been one of the most heatedly debated and often misunderstood issues in Guild history. "They have been saying for ages that possession is nine-tenths of the law, and as we've said, directors have possessed possessory credit since the dawn of cinema," proclaimed a story in a 1967 edition of the DGA's Action! magazine.

Most commonly expressed as "a film by," the credit serves multiple purposes and is a vital representation of the director's role in the filmmaking process. It not only recognizes his or her artistic achievement and skill in orchestrating the collaborative process of filmmaking, but is also a branding tool that can enhance the value of a project. The possessory credit also prevented the abuse of the director credit by making sure it was not awarded on an arbitrary basis.

The tradition of the possessory credit was challenged in 1966 by the Writers Guild of America west. In secret negotiations with the AMPTP, the WGAw was able to bar producers from awarding the "film by" credit to anyone other than a writer entitled to credit on the screen or the author of the source material. Many of the DGA's most illustrious directors formed an action committee that held a historic meeting on May 16, 1967, where even Alfred Hitchcock, who was rarely seen at meetings, was in attendance. The emotional high point of the meeting was the reading of a telegram from David Lean, which, in part, stated that, "We directors who have possessory credits have hard-earned them over many years for good reason..."

"Everybody was aghast and against it," later recalled George Sidney, who was DGA president at the time. DGA leaders sent the AMPTP a telegram stating that the Guild would not "accept or abide by your attempt to bargain away, in private, rights of motion picture directors which have been long established by industry custom and practice." Facing the threat of a strike by the DGA, the AMPTP reversed course and affirmed the right of anyone to negotiate for special credits and enshrined that principle in the DGA Basic Agreement.

Over time, the DGA has sought to address the general proliferation of credits and, in 2004, under the leadership of President Michael Apted and National Vice President Steven Soderbergh, the Guild voluntarily altered the standards by which possessory credits can be awarded to DGA feature film directors. The key provisions now bar a first-time director from receiving the credit unless they brought the property that was the basis of the film to the studio and provided substantial services to the development. The Guild proposed several non-binding guidelines for employers to consider granting the possessory credit, including whether a director has established a marketable name or signature style of filmmaking.

"The possessory credit has stood as a trademark of the very best in film direction since the birth of the American film industry," says DGA President Michael Apted. "Over the years, this worthy credit has been accorded to those directors whose particular contributions to their films entitled them to it, and afforded them recognition among movie-goers."

2000s - DGA Honors New York

Brothers: Robert De Niro backstage after receiving the DGA Honor in 2004

Brothers: Robert De Niro backstage after receiving the DGA Honor in 2004 with his longtime collaborator Martin Scorsese. (Credit: Robert Hale)

Launched in 1999, DGA Honors is the Guild's most significant New York event, gathering filmmakers, celebrities, politicians and industry leaders to celebrate the achievements of leaders in their fields. With celebrity presenters and a gala reception, DGA Honors has become a landmark event and a demonstration of the Guild's commitment to the East Coast industry.

Ed Sherin was the visionary force behind DGA Honors. "Honors was created to help remedy the historic lack of recognition for the increasingly important role being played by New York and the eastern region of the United States," says Sherin, who conceived of DGA Honors after he was elected national vice president in 1997. "Naturally, our focus is on the creation of terrific film and television. But the Guild is also uniquely positioned to honor the diversity of achievement which helps drive our industry from behind the scenes."

The DGA Honors Filmmaker Award was first presented to Martin Scorsese, followed by Mike Nichols in 2000, Spike Lee in 2002, Robert Altman in 2003, Robert De Niro in 2004 and Arthur Penn last year. The John Huston Award for Artists Rights has been awarded three times - first to Sydney Pollack in 2000, then Elliot Silverstein in 2002 and most recently to Bertrand Tavernier in 2004. Curtis Hanson received the Film Foundation Preservation Award in 2003, while Jane Alexander, past-president of the National Endowment for the Arts, was honored in 2002, and actor-humanitarian Danny Glover was recognized in 2006. Other filmmakers who have been honored include Jonathan Demme and Joe Pytka.

Among the leaders in labor, business and politics who have been honored for their support of directors are IATSE President Thomas C. Short, AFL-CIO President John Sweeney, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, New Line Cinema founder and CEO Robert Shaye and HBO chairman and CEO Jeff Bewkes.

"All of the recipients are truly exceptional - vibrant examples of how committed individuals and organizations can assist in the growth, integrity and preservation of the film and television industry - and positively impact our country through their important contributions," says Apted.

2000s - Councils from Coast to Coast

Brain Trust: (left to right) Western AD/SM/PA Council Chair Scott L.

Brain Trust: (left to right) Western AD/SM/PA Council Chair Scott L. Rindenow, DGA President Michael Apted and Western AD/UPM/TC

Council Chair Cleve Landsberg. (Credit: Robert Hale)

The 1960 merger of the SDG and the RTDG gave the newly named Directors Guild of America both a major presence on the East Coast and significant jurisdiction in television, including the representation of the associate directors and stage managers who were part of television directors' teams.

The entry of these new members, combined with the merger of the IATSE Local that represented unit production managers in 1964, led to the formation of new member Councils to speak for these categories within the Guild. Although assistant directors working in feature film had been a part of the Guild since its inception, this influx of new below-the-line membership necessitated changing the former Council structure.

Four new Councils were created to meet the needs of members: the AD/UPM Council East and the AD/UPM/TC Council West (which also represents Technical Coordinators), and the AD/SM/PA Council West and AD/SM/PA Council East. Each of these four Councils has unique concerns, but all share the common goal of active representation of members in their job categories.

"The Councils on both coasts encourage members to bring issues to our attention so they can be addressed," according to Louis J. Guerra, chair of the AD/UPM Council East. Adds Dennis W. Mazzocco, chair of the AD/SM/PA Council East, "We have a regular, ongoing dialogue with members who are active in their field and are able to bring work experience, contacts and information that they gather on a day-to-day basis to the Council meetings."

Eastern AD/UPM Council Chair Louis J. Guerra

Eastern AD/UPM Council Chair Louis J. Guerra

Eastern AD/SM/PA Council Chair Dennis W. Mazzocco

The primary mission of each Council is to serve as the venue for member participation in the workings of the Guild. The Councils are where members can hear on a regular basis about Guild policies, while leadership gets to hear about the concerns of members in these categories. Council leadership has the responsibility to keep members current on labor-contract issues, while encouraging them to share concerns about safety procedures, working conditions and employment.

All four Councils have numerous subcommittees and sponsor Guild events designed to hone their craft and careers. "Our members face many challenges to adapt to new technologies and evolving business models," says Cleve Landsberg, chair of the AD/UPM/TC Council West. "Each member must stay current with these changes, and the Councils and the DGA work to help our members achieve this."

Council members serve as mentors when possible, and occasionally take new members to work so they can experience different types of jobs. Since the Councils are constantly striving to stay up to date, members are encouraged to attend meetings to keep informed. "Our purpose is to generate interest in our current environment and in protecting our future through negotiations, training and education," adds Scott L. Rindenow, chair of the AD/SM/PA Council West.

2000's - Negotiating Table

Mission Accomplished: The two sides shake hands after an

Mission Accomplished: The two sides shake hands after an agreement is reached in 2004.

Negotiations occur with such regularity, about every three years, it's easy to forget how far directors and their teams have come in a relatively short time. Residuals, pension, health, minimums, director's cut, credits - just about everything that DGA members now take for granted were achieved through high-stakes negotiation between the Guild and representatives of the studios, networks and producers.

"From the moment a Guild member takes a project, and in perpetuity through residuals, what it means to be part of a DGA team came about through decades of negotiation, a lot of hard work and planning," says Jay D. Roth, national executive director and chief negotiator since he joined the Guild in 1996.

Negotiations have achieved fundamental gains in economic and creative rights, as well as credits, qualification lists, the grievance and arbitration process, and other areas affecting members. Economic advancements range from base-level minimum wages and working conditions to residuals, pension and health plans and jurisdiction over existing or emerging forms of production.

The Guild's major contracts are the Basic Agreement, the Freelance Live and Tape Television Agreement, the Network Agreement and the Commercials Contract. The Basic Agreement was established soon after the then-Screen Directors Guild was recognized by the studios as a collective bargaining unit in 1939. While the BA covered feature film work, a separate contract, the Network Staff Agreement, arose in the 1950s to cover staff and freelance employees at ABC, NBC and CBS. The rise of independently-produced live and taped television production in the 1970s led to the FLTTA. A separate Commercials Contract covers members in that field.

Creative rights arose to protect the artistic integrity of the director, from time allotted for preparation to the right to a director's cut and participation throughout post-production. Prior to 1964, directors had no guaranteed right to deliver their cut of a film or TV program. Unless they had the clout to negotiate that right, directors were limited to viewing the first rough cut and making suggestions to an associate producer. Concern about this issue led to the concept of creative rights and, in 1964, a negotiated right to a director's cut. Dozens of other rights have followed, enabling directors to better realize their vision.

Most negotiations follow a basic pattern. The DGA president appoints, and the National Board approves, a chair or co-chairs as well as members to serve on a negotiating committee. For the Basic Agreement, the President also appoints the Creative Rights Committee and Chairs. The committees work with staff to fashion bargaining proposals that are presented to the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (in the case of the BA and FLTTA), the networks (for the Network Agreement), and the Association of Independent Commercial Producers (for the Commercials Contract). The DGA's national executive director serves as chief staff negotiator for the BA and FLTTA, while the eastern executive director is chief staff negotiator on the Network Agreement and Commercial Contract. Members who have chaired the committees include, most recently in 2004, Gil Cates for the BA/FLTTA, William M. Brady for the Network Agreement, and Steven Soderbergh and Jonathan Mostow as co-chairs of the Creative Rights Committee. Once a tentative agreement is reached, it is presented to the DGA National Board to recommend whether to send it to members for final approval through balloting.

Beginning in 1981, the Basic Agreement and FLTTA have been negotiated at the same time. A major advance was made in 2001 in reconciling the agreements so employment conditions are consistent depending on whether a program is shot single- or multi-camera, as opposed to the outdated distinction of film vs. tape. The Network Agreement has also been negotiated concurrently with these other agreements since 1981. The Commercials Contract has received increased attention in the past 10 years, leading to notable advances in terms and conditions, including substantial increases in pension and health contributions, expanding jurisdiction to cover all commercials in all media, and establishing a commercial report system to formally track commercials. While the DGA has gone on strike only once, the Guild has formed strike committees and prepared members for action in difficult talks.

"Negotiations are the fundamental means by which the Guild protects and enhances its members' economic and creative rights in the industry," said DGA President Michael Apted. "The DGA will continue to vigorously pursue those goals in all of our contracts, which are the great legacy of the Guild."