BY GARY GIDDINS

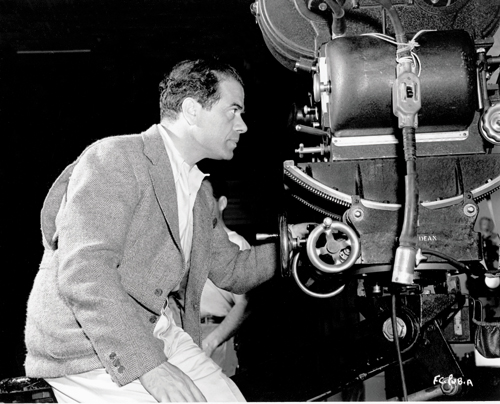

Frank Capra Directing Meet John Doe (1940) (Credit: Photofest)

Frank Capra Directing Meet John Doe (1940) (Credit: Photofest)

Fairy tales play an ambiguous role in American culture. We accept those appropriated from the Old World, blithely passing them to our children in cleaned-up versions. It's the homegrown moral mythologies and foundation stories on which we were raised that are so troublesome. No filmmaker has shown a more acute appreciation for those American fairy tales than Frank Capra; and no one has done more to relocate them in the world most of us inhabit, as opposed to the Old West, outer space, or the urban underworld.

Capra's myths are not the tall stories of Pecos Bill, John Henry or Paul Bunyan, but rather those that define our initial understanding of history: the founding fathers as Romanesque gods; the melting pot that welcomes and assimilates all races and creeds; the innocence we are forever claiming to have lost. As recently as the 1950s, elementary school students were instructed in Washington's parable of exemplary truth, only to learn at a later date that the cherry tree belongs to the realm of Santa Claus and the tooth fairy. Capra knows the cherry tree is a lie, but he isn't convinced that it's a useless lie.

As John Ford also understood, we want it both ways: Know the truth but print the legend. Capra's oddly stunted career illustrates the broad cultural ambivalence about who we think we are. Once upon a time, he had few, if any, rivals among American directors. Spinning variations on his signature story in which good triumphs over hypocrisy and greed, he created an alluring fable that surely helped his audience to make sense of and survive the Depression. For that, Capra received an unparalleled number of awards as well as the kind of handwritten possessory credit later associated with Walt Disney.

Yet his reign was brief. Though his career lasted nearly 40 years, ranging from ingenious silent comedies with Harry Langdon to a few undervalued postwar pearls, he was honored almost exclusively for the work of six years, 1934-39. After the war, during which he made a widely admired series of propaganda films, Why We Fight, Capra's view of life lost its appeal, and was often misrepresented with the derisory epithet "Capracorn." His Christmas carol, It's a Wonderful Life, played to empty theaters in 1946, and his subsequent elaborations on old ideas seemed sentimental and remote. Put another way, our response to Capra's work mirrors his patented fable: We initially watch it with the happy credulity of a Mr. Deeds or Mr. Smith, then ruefully return to it as the cynic determined to cut them down to size.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

(Credit: Sony Pictures Home Entertianment/GciGroup)

The power of a good fairy tale is that while it may be put to sleep, it can never be put to rest. The 1980s television resurrection of It's a Wonderful Life proved Capra's resilience. The newly released Premiere Frank Capra Collection, collecting the five major Depression-era films he made for Columbia Pictures, confirms his ongoing relevance as well as the technical beauty of his work. (The delight of rediscovering them is vastly enhanced by outstanding prints; indeed, the digitalization of Mr. Deeds is so sharp it has the unfortunate side effect of highlighting the frequent use of process shots.)

Not that we need to be reminded of Capra's dramatis personae. The culture has long since assimilated his characters - Jefferson Smith, Longfellow Deeds and John Doe are part of our language. Yet seeing these five pictures - American Madness (1932), It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), You Can't Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) - all at once underscores his obstinacy in attempting to reassert an American myth involving the conquering rube, the smitten cynic, and the alternately malignant and benign mob. His ultimate faith in the mob - the little guys - in an era beset by mob violence is the essence of Capra's America.

Fairy tales involve moral awakening. For Capra, that literally means the sleeping child in cynical adults - the dormant idealist who upholds the promise of American rectitude despite layers of corrosive distrust. Seeing Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington today, it seems evident that the real hero isn't the rube, who, Capra makes clear, is too dumb or innocent to survive alone. The person who saves the day is a hard-bitten city gal (Jean Arthur in both films), whose idealism is roused by love and who acts on it with a grown-up's knowledge of the way things work.

It Happened One Night (1934)

It Happened One Night (1934)

(Credit: Sony Pictures Home Entertianment/GciGroup)

Capra's theme is not that politics is tainted by money; he takes that as a given. He is concerned with a more intriguing paradox: Idealism is corrupted by maturity, but in the absence of maturity, idealism is worthless. He offers a miniature allegory in the first montage in Mr. Smith, as Jeff Smith (Jimmy Stewart) tours the Capitol and is moved not only by the monuments, but by the very young and very old visitors who gullibly cherish myths Capra believes are worth cherishing. The film's plot turns on a contest between boys, who, in effect, appoint Smith to the Senate, and men, who, as the devious Senator Payne (Claude Rains) takes pains to explain, do work that boys cannot possibly fathom.

Capra departs from traditional fairy tale narrative in setting his stories in the present rather than a distant past. Otherwise, they conform to a structure that involves magical interventions on behalf of mortal heroes. He often refers to fairy tales in structuring his work, never more so than in his freely adapted version of the George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart play, You Can't Take It with You, in which a lovers' spat is characterized as Cinderella spurning her prince. Her family's basement is depicted as a dominion of elves in smocks, making toys and fireworks and whistling "Whistle While You Work," aided by a crow who answers to the name Jim. As the prince Tony (Stewart), observes, this is a family Disney might have dreamed up.

Like all good fairy tales, Capra's films rely on miraculous circles, rituals, and denouements. The circles are often embodied by rings of good people united by song - group-sing from which the snobs and crooks are self-exiled. Music plays an important role in setting things right. Capra's Depression classics not only capture the look of the 1930s, with their urban montages, masses of extras, wisecracking reporters, ruthless plutocrats, and rural Edens (Mandrake Falls and Bedford Falls are similar wombs of goodness), but also the sound of the era. This despite the fact that he does his best to avoid contemporary music; his 1930s have little relationship to the Swing Era - in It's a Wonderful Life, he uses jazz as a symbol of degradation.

American Madness (1932)

American Madness (1932)

(Credit: Sony Pictures Home Entertianment/GciGroup)

In the virtually perfect It Happened One Night, which all but invented screwball comedy, singing "The Man on the Flying Trapeze" with a group of fellow travelers brings Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert together, while gunning the plot by sending their bus off the road. In a performance of timeless candor, Gable constantly lectures her on trivialities - directly prefiguring Seinfeld in clamping on a word and stretching it into nothingness. She can't dunk a donut, piggyback, or hitchhike, though she holds her own regarding the last. In song, however, they are at peace.

You Can't Take It with You has two important songs. In one sequence, James Stewart and Jean Arthur escape their families to sit on a park bench and discuss courage. Capra's courage is evident as he shoots the entire scene in one unbroken five-minute take, the camera never moving, trusting entirely to the actors to make it work. Their reward is to dance the big apple (a rare acknowledgement of contemporary pop) with some very hip kids. The movie's big number, though, is the characteristic "Polly Wolly Doodle," which not only magically reunites the lovers but converts the soulless tycoon into a regular guy.

The distinctive sound of Capra films goes beyond music; it's there in the crowd noises, the drunken revelry, the alternating shouts and murmurs, the fast-talking rumor mill that feeds on fear and contempt and often leads to a courtroom climax, overseen by a benign judge coyly suppressing his delight in the will of the people. Rumors corrupt the body politic, leading to the disastrous bank run in American Madness, Capra's breakthrough film. In a challenge to the faith of the people's banker, Walter Huston declines from peacock energy to sodden deflation; yet ultimately, the mob will rise in a crescendo of American decency, restoring his faith.

Capra on set of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Capra on set of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

(Credit: DGA Archives)

Another fairy tale convention recharged by Capra is the intercession of a plain-spoken stranger: a starving farmer makes Deeds see the light; a destitute businessman shows up the tycoon in You Can't Take It with You. In Mr. Smith, Capra's most despondent and emotionally multifaceted film, however, not even a children's crusade can save Jeff Smith. The kids are mauled and possibly killed by thugs, causing Jean Arthur to call an end to Smith's filibuster. He can't beat the corrupt machine run by Jim Taylor (Edward Arnold, in a superbly nuanced portrait); 90 seconds before the film ends, Smith collapses, destroyed. Yet in those last seconds, Senator Payne intercedes, bursting into the Senate chamber to confess his guilt. This is not an ending mandated by the Production Code; it's the point of the film.

Mr. Smith is a parable of destroyed innocence, and a far more devastating portrait of American politics than Otto Preminger's admirable Advise and Consent, let alone recent schmaltz like Dave or Man of the Year. In 2006, the film had particular resonance: The plot is launched when the Senate loses one Senator Foley, and prototypes for Jack Abramoff and Tom DeLay are obvious. The 90-second turnaround fulfills the demand of Capra's fable: What's really at stake is not Smith, but those axiomatic American myths he embodies. Capra might have concluded the film with a mass of boys triumphing on Smith's behalf. Instead, Capra unleashes his brand of pandemonium over Jeff's unconscious body - it's a miraculous victory, beyond Jeff's limited powers. The kingdom will prevail, but it's a close call.