BY SYLVIANE GOLD

TRUE TO LIFE: Julie Taymor combines the realistic with the fantastic

TRUE TO LIFE: Julie Taymor combines the realistic with the fantastic

in Across the Universe. (Credit: Abbot Genser/Revolution Studios)Most film directors hope audiences will forget they're in a theater watching a movie. Not Julie Taymor. She wants them in her story. But she also wants them outside it, watching the medium trick them.

To that end, she set her Shakespeare adaptation, Titus, in a blatantly manufactured ancient Rome, with armored tanks and video games sharing the screen with colonnades.

In her second film, Frida, she repeatedly froze the action in tableaux duplicating the surreal paintings of Frida Kahlo.

And with her new movie, Across the Universe, Taymor again blends the true-to-life with the artificial, harnessing the music of the Beatles and the helter-skelter imagery of MTV to tell a period love story.

Taymor doesn't buy the prevailing view of film as a purely literal medium, and it bothers her that its arsenal of special effects is usually employed in the service of naturalism. "Whether it's Superman or Titanic," she notes, "it's almost always to make it real. The only time that they've gone very far out with visual effects is in things like The Matrix." She wants it both ways for her films; to go far out while telling a believable story.

Her refusal to use film simply to record reality flows directly from her background in theater and opera, where reality is moot. "You can't be literal in the theater," says the director of The Lion King. "Its limitations force you to find an alternate way of creating scenes. You have to abstract a swamp or a battlefield." That habit of mind infuses her moviemaking: "You ask yourself, 'How much literalness do you need?'"

Across the Universe, which opens in spring 2007, marks the first time she's been able to give her visual inventiveness such free rein on film. "Music videos have done an extraordinary job with imagery that you rarely see done in movies," she says. Appropriating those techniques, along with 35 Beatles songs culled from their output of 200, she follows six young people through the cultural, political and sexual upheavals of the 1960s. As in more traditional movie musicals, the songs are performed by the actors, some of whom had never sung in public.

The Beatles are neither seen nor heard in the film—the idea was to make the songs "the speech, the minds, the thoughts, the arias that are coming from these characters." Working with screenwriters Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, she based two of the characters, Lucy and Max, on her own siblings. Taymor was 10 in 1963, when the film begins. "I lived through that era as a voyeur. I experienced it through my older brother and sister." And Lucy, who falls in love with Jude, a boy from Liverpool, includes a dash of Taymor herself, and it's not just that they both grew up in the suburbs of Boston. "She's got an edge to her. I wanted her not to just be the love interest."

Although she conceived Across the Universe as a visual extravaganza, Taymor's concern with character is not incidental. "I love working with actors," she says. Much of their rehearsal time was necessarily spent learning the songs and how to perform them, she says, but she did not ignore the book scenes. "It was like doing theater. It was just as intimate." She also sometimes took her leads with her when she was scouting locations. "It would give us a lot of ideas, and we could work it through with them on the spot."

The film has only 30 minutes of dialogue, but, she says, "It is definitely a narrative, linear, cinematic story that takes you all over the map of that time. We're in subways, battlefields, helicopters, riots, bedrooms, schools, gymnasiums. Each song was conceived to take you to a different place. And instead of having production numbers that are just pure dance, which is what Broadway does, I use other techniques—animation and collage—to create what I would call production numbers in film."

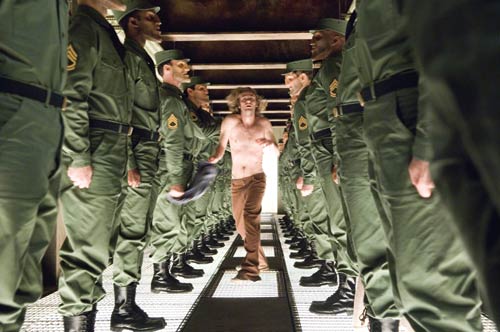

One of her favorites begins when Max is summoned to the army induction center in Manhattan. Taymor transforms this matter-of-fact scene into a phantasmagoria by using simple 2-D animation: the Uncle Sam poster on the wall suddenly sprouts moving lips that sing, "I want you. I want you soooo baaaad." The song continues on the soundtrack as Taymor shoots real hands throwing Max onto a real conveyer belt, part of a stylized factory set created by production designer Mark Friedberg.

In the next shot, the song is taken up by a squadron of identical soldiers in prosthetic makeup doing Danny Ezralow's robotic choreography. Masks would have worked, Taymor says, but she went with the makeup so she could shoot them actually singing. Of course, that meant she had to work quickly, since the makeup had a tendency to melt under the lights.

As Max travels down the conveyer belt, the soldiers, still singing, strip off his clothes. Next, in a CGI montage that fills the screen, Taymor's shots of Max's body parts being measured, poked and prodded with medical instruments are encased in what she calls "Cornell boxes." The pile-up of images, she says, is intended to drive home the idea that Max is being "processed, like a side of beef." And in the grand finale, Max envisions himself and the other recruits dressed only in jockey shorts and army boots, trampling a small-scale Vietnamese landscape. Taymor has the camera pan up slowly from their feet to reveal that they are carrying the Statue of Liberty. The accompanying lyric? "She's so heavy!"

The idea for the shot came to Taymor on a Mexican beach, where she was discussing the sequence with Elliot Goldenthal, the composer who wrote the film's original score and rearranged all the Beatles tunes to match the characters and situations. "I knew I needed to do an induction scene as I was listening to the songs," she says. "When I came across 'I Want You,' my mind immediately went to Uncle Sam." The Statue of Liberty bit was "an image that just came to me, like so many others. You can't know why."

Taymor had a 30-foot replica of the statue sculpted and had Vietnam-in-the-studio built with dirt and hundreds of miniature palm trees. From a crane, she filmed the soldiers trampling it against a blue screen, adding the sky and shafts of light later. To ease the weight for the actors and to stabilize the statue, she had it suspended on wires.

WALK THE LINE: A draftee gets processed on the army conveyor belt

WALK THE LINE: A draftee gets processed on the army conveyor belt

in the "I Want You" number in Julie Taymor's Across the Universe.

(Photo Credit: Abbot Genser/Revolution Studios)Clever and complicated as it is, the induction sequence looks simple beside the most complex of the production numbers, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite." For that one, Taymor took cast and crew to a park in Garrison, New York, where she filmed Eddie Izzard, in black top hat and tailcoat, singing the song with a vast ensemble. But the finished number is a wild, hallucinatory trip—in the '60s meaning of the term—created with 900 layers of computer-generated imagery.

Taymor is careful to credit her collaborators. With Friedberg and Albert Wolsky, her costume designer, she "talked a lot about the color palette—in Liverpool, the browns, the blues, the grays, the rain in winter; in Brookline, the pastels, the golden colors." She also encouraged them to capture the contrast between "the narrow lines and deep, deep focus" of Liverpool's back lanes and the "horizontal, wide-open lines" of American suburbs.

Taymor's involvement in the look of a film extends even to the extras. There are 5,000 of them in Across the Universe, and she vetted every one. "Faces are really important," she says. "Maybe it goes back to being a Fellini fan." She pushed to shoot in Liverpool, she says, not just for its shipyards and harbor vistas but for its weather-beaten, working-class faces.

She insisted on verisimilitude in the dancing, too. "I've Just Seen a Face" is set in a bowling alley. At the "falling, yes I am falling" lyric, bowlers start collapsing, slipping and sliding down the oiled alleys. "A dance can be made out of a real situation," she says. "That's how Danny and I approached it—that the dance numbers were about walking or turning or the situation."

A SPLENDID TIME: The ringmaster Mr. Kite (Eddie Izzard) performs

A SPLENDID TIME: The ringmaster Mr. Kite (Eddie Izzard) performs

with his circus in Julie Taymor's Across the Universe.

(Photo Credit: Abbot Genser/Revolution Studios)Taymor shot some dance in the studio, but many of the sequences, like the bowling-alley scene, were done on location. One number begins with the camera, on a motion-control track, circling a single dancer. "Then there's 10 and then there's 40 and then there's 100," Taymor says. "We keep adding them, but it looks like the camera didn't stop moving." (She also used motion control to shoot Salma Hayek, as five different sexpot nurses, singing five-part harmony with herself.)

Much as she loved moving the camera around Ezralow's choreography, she found the dance numbers the hardest to shoot. Storyboarding helped some, but on the whole, she preferred leaving her options open: "I found it encroached on my creativity," she says. The film's action scenes—demonstrations, riots and battles—gave her less trouble, because she wanted them to look like the news footage she'd seen while researching the period. "So we just used two or three handheld cameras. It is very different from setting up complicated moving tracking shots."

Towards the end of the shoot, she clustered all the remaining blue screen work and hired two more DPs to help finish the movie. "We had five blue screens going on at the same time," she recalls. "It was a three- or four-ring circus that last week." Others might have found it scary or nerve-wracking. Not Taymor.

"It was wonderful," she says.