BY WILLIAM FRIEDKIN

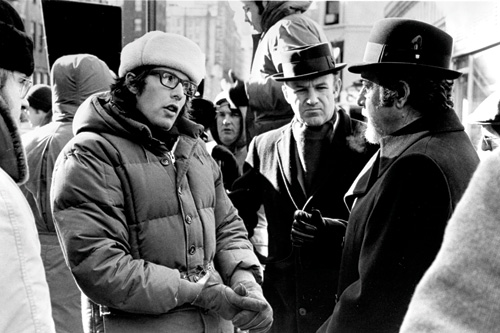

MAKING MAYHEM: Friedkin on the set with The French Connection's

MAKING MAYHEM: Friedkin on the set with The French Connection's

stars Gene Hackman (center) and Fernando Rey. (Credit: AMPAS)

About 28 years ago, producer Phil D'Antoni told me the story of The French Connection. It was then a book he had just optioned, based on the true story of an important narcotics investigation that took place in New York City between 1960 and 1962. I thought it was a terrific story filled with fascinating characters.

The narrative as set forth by Robin Moore in his novel contained all the raw material for an exciting film. Two tough New York cops are trying to intercept a huge heroin shipment coming from France. They put a tail on the suspects, headed by a suave Frenchman they dub Frog Number One. It had everything...almost. D'Antoni and I were in full agreement on one point: what we needed most of all was a powerful chase. In fact, our thinking frankly followed formula lines: A guy gets killed in the first few minutes; checkerboard the stories of the cop and the smuggler for approximately 20 minutes; bring the two antagonists together and tighten the screws for another 10 minutes or so, then come in with a fantastic 10-minute chase. After this, it was a question of keeping the pressure on for another 20 minutes or so, followed by a slam-bang finish with a surprise twist.

D'Antoni had been the producer of Bullitt, which offered what was probably the best car chase of the sound film era. It was because of this that I felt challenged to do another kind of chase, one which, while it might remind people of Bullitt, would not be essentially similar.

I felt that we shouldn't have one car chasing another car. We had to come up with something different; something that not only fulfilled the needs of the story, but that also defined the character of the man who was going to be doing the chasing—Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman), an obsessive, self-righteous, driven man.

At this point, I should say that I thought the chase sequence in Bullitt was perhaps the best I had ever seen. When someone creates a sequence of such power, I don't feel it's diminished if someone else comes along and is challenged to do better. The chase in Bullitt works perfectly well in its own framework, and so, I feel, does the one in French Connection. When a director puts a scene like that on film, it really stands forever as a kind of yardstick to shoot for, one that will never really be topped, that will always provide a challenge for other filmmakers.

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

Gene Hackman trying to catch the subway in director

William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971).CONCEPT

After I had agreed to direct the film, D'Antoni and I spent the better part of a year working on what turned out to be two unimaginative, unsuccessful screenplays. The project was eventually dropped by National General Pictures, and lay dormant for about 10 months. Every studio in the business turned the picture down, some twice. Occasionally, we would get a glimmer of hope, and during one such glimmer, we contacted Ernest Tidyman, who had been a criminal reporter for The New York Times, and had written a novel called Shaft, the galleys of which D'Antoni had read and passed on to me. Tidyman had not written a screenplay before. But we felt, because of what we read of Shaft, that he had a good ear for the kind of New York street dialogue we wanted for The French Connection.

Tidyman agreed to work with us on an entirely new script. Up to this point, we had a storyline that was pretty solid, but we had nothing in the script that indicated the kind of chase we eventually wound up with. We had spent a year and gone through two screenplays without indicating what the chase scene would be—because we didn't really have one.

One day D'Antoni and I decided to force ourselves to spend an afternoon talking, with the hope that we could crack this whole idea of the chase wide open. We took a walk up Lexington Avenue in New York. The walk lasted for about 50 blocks. Somewhere during the course of it, the inspiration began to strike us both, magically, at the same time. It's impossible for either one of us to recall who first sparked it, but the sparks were fast and unrelenting.

"What about a chase where a guy is in a car, running after a subway train."

"Fantastic. Who's in the car?"

"Well, it would have to be Doyle."

"Who's he chasing?"

"Well, that would have to be Nicoli, Frog Number One's heavy-duty man."

"How does the thing start?"

"Listen, what would happen if Doyle is coming home after having been taken off the case and Nicoli is on top of Doyle's building and he tries to kill him?"

"...and in running away, Nicoli can't get to his car."

"Doyle can't get to his."

"Nicoli jumps on board an elevated train and the only way Doyle can follow is by commandeering a car."

"Terrific."

And so on.

During that walk, D'Antoni and I ad-libbed the entire concept of the chase to one another, each building upon the other's thoughts and suggestions. The next afternoon, we met with Tidyman and dictated to him our mutual concept. Tidyman took notes, then went off and put the thing in screenplay form. At this point, the chase was all we needed to complete a new draft of the script. The original draft of the chase ran about five or six pages of screenplay. It was very rough and didn't have the benefit of research to establish whether or not what we were proposing was possible.

The script in its new form was submitted to 20th Century Fox, namely David Brown and Dick Zanuck, who decided to make the picture.

It then fell to me to determine how we could go about shooting this sequence, which we always considered to be the most important element in the film. First, we had to contact the Metropolitan Transit Authority of New York City. Our associate producer, Kenny Utt, together with production manager Paul Ganapoler had a series of meetings with the public relations representative for the Transit Authority, who agreed in principle to our concept, but told us that there were numerous inaccuracies involved in what we were proposing. He said that everything having to do with the operation of the elevated train was inaccurate. We were suggesting that the runaway train crash into a stationary train that was just outside the station, but it was not possible for such a crash to occur because of safety precautions. He said that if we would agree to more accurate details, he would allow us to use the facilities of the Transit Authority.

Utt, Ganapoler and I met, together with representatives of the Transit Authority Engineering, Safety and other departments, all of whom criticized the sequence as written. They indicated to us what would be more accurate. Happily, their suggestions were more exciting than what we had conceived.

One thing the Transit Authority people were adamant about: there would be no crashing of the two trains. We agreed to this. We ultimately came up with a suggestion of a crash, but not one that is graphically presented. I worked with the TA people for several weeks. Then I went ahead and wrote a new sequence that was considerably longer than the first and more accurate in terms of what would actually happen, given the fictional circumstances that we devised. This sequence was approved by the Transit Authority and we had a go-ahead.

EXECUTION

As everyone knows, most films are not shot in sequence. Our chase scene was shot entirely out of sequence, and over a period of about five weeks. It did not involve solid day-to-day shooting. One reason was that we were given permission to use only one particular Brooklyn line, the Stillwell Avenue, running from Coney Island into Manhattan. After numerous location scouting trips with Utt and Ganapoler, we found a section of the Stillwell Line that we thought would be ideal, stretching from Bay 50th Street to 62nd Street.

It seemed right because the Marlboro housing project was located just two blocks from the entrance to the Bay 50th Street Station. The project was perfect for Doyle's apartment building, and it stood directly across the street from the Stillwell track.

Together with Utt, Ganapoler, my cameraman, Owen Roizman, and the first assistant director, Terry Donnelly, I proceeded to plan a shooting sequence. We knew that in shooting in the middle of winter, we might run into a number of unforeseen problems. But no one could have guessed at some of the ones we were eventually hit with.

I decided to divide the shooting into two logical segments: the train and the car. They had to be shot separately, of course, but at times we had to have both for tie-in shots. I had hoped for bad weather because it would help the look and the excitement. But, of course, I also hoped for consistent light. We told ourselves that even if the light was not consistent, we had to shoot anyway—our schedule and our budget demanded it. I would try to accommodate the cameraman if the light was radically different from day to day. If we had a weather report saying the light was going to be different on one day from what it was on the preceding day, we would try to schedule something else. This occurred on a number of occasions.

As it happened, the New York winter of 1970-71 was not a mild one. Although there was little snow or rain, there was a great deal of bright sunlight. It was painfully cold through most of December and January, when the chase was filmed. Very often it was so cold—sometimes five degrees above zero—that our camera equipment froze, or the train froze and couldn't start. One day, the special effects spark machine didn't work, again because of the cold. Once, the equipment rental truck froze. We seldom had four good hours of shooting a day while inside the train.

A part of our concept was that the pursuit should be happening during a normal day in Brooklyn. It was important that we tie in the day-to-day activity of people working, shopping, crossing the street, walking along, whatever. This meant that while the staging had to be exciting, we had to exercise great caution because we'd be involving innocent pedestrians.

Street to 62nd Street, a total of eight local stops and about 26 blocks. But there was a catch: we could only shoot between the hours of ten in the morning and three in the afternoon. This was the time between the rush hours. Quitting at three o'clock was a hardship, because it meant we would only have half a day to shoot with the train. Starting at 10 was also a problem, because we had to break by 1 p.m. for a one-hour lunch. This meant, in effect, that we really had less than five good hours of shooting each day. It also meant that we would have to be so well-planned that every actor, every stuntman, and every member of the crew knew exactly what was expected of him. It meant that I would have to lay out a detailed shot-by-shot description of what was going to wind up on the screen before I had shot it.

THE BEST-LAID PLANS

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

Gene Hackman trying to catch the subway in director

William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971).

Five specific stunts were planned within the framework of the chase. These were to occur along various points of the journey of the commandeered car. They were to be crosscut with shots of Doyle driving fast and with the action that was going on in the train above.

A word about the commandeered car: It was a brown, 1970 Pontiac, four-door sedan, equipped with a four-speed gearshift. We had a duplicate of this car with the back seat removed so we could slip in camera mounts at will. The original car was not gutted, but remained intact so that it would be shot from the exterior.

The entire chase was shot with an Arriflex camera, as was most of the picture. There was a front bumper mount, which usually had a 30- or 50-millimeter lens set close to the ground for point-of-view shots. Within the car, there were two mounts. One was for an angle that would include Hackman driving and shoot over his shoulder with focus given to the exterior. The other was for straight-ahead points-of-view out the front window, exclusive of Hackman.

Whenever we made shots of Hackman at the wheel, all three mounted cameras were usually filming. When Hackman was not driving, I did not use the over-shoulder camera. For all of the exterior stunts, I had three cameras going constantly. Because we were using real pedestrians and traffic at all times, it was impossible to undercrank, so everything was shot at normal speed. In most shots, the car was going at speeds between 70 to 90 miles an hour. This included times when Hackman was driving, and I should point out that he drove considerably more than half of the shots that are used in the final cutting sequence.

While it was desirable to have Hackman in the car as much as possible, we hired one of the best stunt drivers from Hollywood, Bill Hickman, to drive the five stunts. Consulting with Hickman, I determined what the stunts would be, trying to take advantage of the particular topography of the neighborhood.

THE FIVE STUNTS

1. Doyle's car driving under the tracks very fast. He looks up to check the progress of the train. A car shoots out of an intersection as he crosses it. Doyle's car narrowly misses this car, spins away and cuts across a service station to get back underneath the elevated tracks.

2. From within Doyle's car, as he pulls up behind a truck, we see a sign on the truck, "Drive Carefully." The truck makes a quick left turn without signaling, just as Doyle tries to pass him on the left, causing a collision and spinoff.

3. Doyle approaches an intersection while looking up at the tracks. As he glances down, an enormous truck passes in front of him, obscuring his view of a metal fence. When the truck pulls away, the fence stands directly in his path. This particular fence was not part of the Stillwell Avenue route. It was something we discovered while location-scouting beneath the Myrtle Avenue Line, another elevated branch several miles away from Stillwell Avenue. I decided to switch locales because of this fence, which suddenly prevented a car from continuing beneath the tracks.

4. Doyle speeds through an intersection against the light. As he does so, a woman with a baby carriage steps quickly off the curb and into his path. Doyle has to swerve and crash into a pile of garbage cans on a safety island.

5. Doyle turns into a one-way street the wrong way to get back underneath the elevated tracks. Over his left shoulder, we see the train running parallel to Doyle, a half-block away.

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

Gene Hackman trying to catch the subway in director

William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971).

On the first day of shooting the chase, we scheduled the first stunt, which was to be Doyle's car spinning off a car that had shot out of an intersection. I had four cameras operating. Two were in a gas station approximately 100 yards from where the spinoff would occur. One was on the roof of the station with a 500 mm lens, and another had a zoom lens on the ground, hidden behind a car. Two more cameras were on the street, directly parallel to the ones in the gas station, also about 100 yards from where the spinoff was to occur.

What we hoped would not happen, happened, causing this shot to be much more exciting than Hickman or I had planned. The stunt driver who was in the other car mis-timed his approach to Doyle's car (with Hickman driving), and instead of screeching to a halt several feet before it, miscued and rammed it broadside. Both cars were accordions, and so on the first shot of the first day of shooting the chase, we rammed our chase car and virtually destroyed it on the driver's side.

Fortunately, neither Hickman nor the driver of the other car were hurt. I was able to pick up the action after the crash with Doyle's car swerving off and continuing on its way. Naturally, right after this spectacular crash occurred, all four cameramen chimed out, "Ready when you are, B.F."

So we were forced to call our duplicate car into service on the first day of shooting, and on all subsequent days when we had to shoot events that would conceivably occur before the crash. To achieve the effect of Hackman's car narrowly missing the woman with the baby, I had the car with the three mounted cameras drive toward the woman, who was a stunt person. As she stepped off the curb, the car swerved away from her several yards before coming really close. But it was traveling approximately 50 miles per hour.

I used these angles, together with a shot that was made separately from a stationary camera on the ground, zooming fast into the girl's face as she sees Doyle's car and screams. This was cut with a close-up of Doyle as he first sees her, and these two shots were linked to the exterior shots of the car swerving into the safety island with the trash cans.

The only other "special effect" was the simulated crash of the trains. Since we couldn't get permission to actually stage a crash, we achieved the effect by mounting a camera inside the "approaching" train, which we positioned next to the train that was waiting outside the station. We had the "approaching" train pull away and shot the scene in reverse, undercranking to 12 frames per second. Just after what seems to be the moment of impact, we included an enormous crashing sound on the sound track, completing the illusion.

For many of the shots with the car, the assistant directors, under Terry Donnelly's supervision, cleared traffic for approximately five blocks in each direction. I had members of the New York City tactical police force to help control traffic. But most of the control was achieved by the ADs with the help of off-duty members of the police department—many of whom had been involved in the actual case.

Working with Donnelly were second assistants Peter Bogart and Ron Walsh, plus trainees Dwight Williams and Mike Rausch. The cooperation of New York City officials was incredible. We were given permission to literally control the traffic signals on those streets where we ran our chase car. We rehearsed a shot in slow motion five or six times before I was satisfied that all safety conditions were met and that the coordination was there. Then we prayed a lot, and kept our fingers crossed.

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

STREETWISE: Shots from the 15-minute sequence of

Gene Hackman trying to catch the subway in director

William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971).

For one particular shot, we used no controls whatsoever. This was a shot with two cameras mounted, one inside and one outside the car. The inside camera was on a 50 mm lens, shooting through the front window; the outside camera was on a 25 mm mounted to the front bumper. I was in the car. Bill Hickman drove the entire distance of the chase run, approximately 26 blocks, at 70 to 90 miles an hour. With no control at all and only a siren on top of his car, we went through red lights and drove in the wrong lane. This was, of course, the wrap shot of the film. I made two takes and from these we got most of the point-of-view shots for the entire sequence.

FINISHING TOUCHES

The question I'm most asked in interviews about The French Connection, is how the chase was filmed. As is obvious from the above notes, it was filmed one shot at a time, with a great deal of rehearsal, an enormous amount of advance planning, and a good deal of luck. But at least 50 percent of the effectiveness of the sequence comes from the sound and editing. The sound was done entirely after the fact. Several months after the completion of shooting and with what looked like a good cut, I went back to New York. With soundman Chris Newman, we created all the sound for the elevated train. Then I returned to California and with Don Hall, the sound supervisor at 20th, made all the sound for the car on the Fox backlot.

We treated the recording of the individual effects with the same care and attention to detail as we did the photographing of the film. The use of effective sound effects is, I feel, as important as the picture. Individual frames or shots or still photographs from the chase are unimpressive. It is the manner in which all the elements are combined, and how sound effects orchestrate the scene, that makes it work.

I can't say too much about the importance of editing. When I looked at the first rough cut of the chase, it was terrible. It didn't play. It was formless, in spite of the fact that I had a very careful shooting plan that I followed in detail. It became a matter of removing a shot here or adding a shot there, or changing the sequence of shots, or dropping one frame, or adding one or two frames. And here's where I had enormous help from Jerry Greenberg, the editor.

As I look back on it now, the shooting was easy. The cutting and the mixing were enormously difficult. It was all enormously rewarding.

Reprinted from the DGA's Action Magazine, March-April 1972.