BY JONATHAN HOLLAND

PASSION PLAY: Almodovar is always on the lookout for miraculous moments

PASSION PLAY: Almodovar is always on the lookout for miraculous moments

from his actors. (© Emilio Perdea & Paola Adrizzioni/Sony Picture Classics)With its brilliant reds and blues, airiness and meticulous layout, Pedro Almodóvar's office in Madrid might be a set piece from one of his films. A poster from All About Eve adorns one wall. On the others are photographs of the director with assorted friends like Antonio Banderas and the fabled Mexican singer Chavela Vargas; and there are posters of his own films, including the one which won the 1999 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, All About My Mother. Even the folded sunglasses on his desk seem to have been carefully positioned. Nothing about his surroundings seems left to chance.

"In my films, I control absolutely everything that can be controlled," he confesses. "Some things will always escape you, but I need to have as much control as it's possible to have."

An amiable, slightly portly figure with a carefully mussed, vivid shock of gray hair, after a quarter of a century and 16 films the 57-year-old Almodóvar no longer looks like the enfant terrible. These days, he's more like the hip, fun uncle you always wished you had. The most acclaimed Spanish-language filmmaker since Luis Buñuel, he makes movies that are both quintessentially Spanish and universal in their emotional concerns, critical of human nature yet compassionate. Taken together, they are a rich amalgam of contradictions whose charm and power have seduced both the global arthouse audience and won him two Oscars (the other was for Best Screenplay for Talk to Her in 2002).

Volver, Almodóvar's latest and most personal work, is set largely in a village in the windswept region of La Mancha in central Spain where Almodóvar grew up. It is the story of how a dead mother returns to help her daughters—one of them played by Penélope Cruz—in ways she could not while she was still alive. Drenched in the intensely autobiographical feeling of a grown man going back to his roots, the film's supernatural elements and relative visual and narrative asceticism make it markedly different from the high artifice generally associated with him. "Volver is an attempt," Almodóvar says, "to tell an apparently ridiculous, grotesque, melodramatic story with the greatest possible simplicity, with absolute naturalness. That was the greatest challenge of the project."

Despite its restraint, the film is instantly identifiable as an Almodóvar piece. "What always attracts me, and it's almost a physical need, is a project that's completely different from my previous ones—like Volver was from Bad Education and like that was from Talk to Her," he says. "But taken together, I think they form a coherent, recognizable whole. There are characters who reappear, returns to previous films. Volver, for instance, has its germ in a novel by an unwritten character in The Flower of My Secret," he says, referring to his 1995 melodrama about a romantic novelist struggling towards emotional independence.

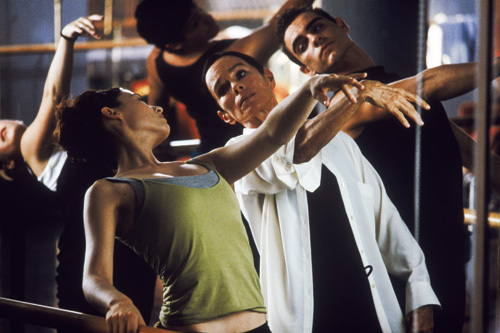

NITTY GRITTY: Carmen Maura and Penelope Cruz as mother and daughter with director

NITTY GRITTY: Carmen Maura and Penelope Cruz as mother and daughter with director

Almodovar on the set of Volver. (© Emilio Pereda & Paola Ardizzioni/Sony)His continuing enthusiasm for his work is evident as he speaks, and he is much given to shooting off on lengthy digressions. Now he spends five minutes exploring the minds and motivations of his characters, discussing them as though they were real people—discussing them, in fact, as though he knows them better than real people.

"My films are character-based," he says, "But it's normally some kind of surprising situation which sparks a film off." The example he gives is from 1991's High Heels. "I saw a TV newsreader [in the film, played by Victoria Abril] saying that someone had died, and I thought it would be great if she followed it up by saying, "and I know who killed her." It is at this point that he enters the mind of the character and develops it.

Almodóvar is a synthesizer of other people's work, drawing together disparate strands of cultural history—'40s noir in his 1997 thriller Live Flesh, '50s melodrama in The Flower of My Secret, contemporary dance in Talk to Her, junk TV in his earlier, more comic work—into the service of his own vision. "I can't say that specific directors have influenced my work in specific technical ways. I don't know to what extent you learn from other directors or not. They're more like a reference, useful so that you can incorporate them as you wish. High Heels, with its expressionist artificiality, could be a Douglas Sirk film; even though it's not actually in the style of Sirk, it's clear that at some level I've been impregnated by his work. And my love of musicals means that I like to include a song in my films. But the song must always serve the story. So Penélope's tango in Volver is about returning."

SOMETHING NEW: Almodovar has a physical need to make his next

SOMETHING NEW: Almodovar has a physical need to make his next

films different from his last. The Flower of My Secret (1995). Live Flesh (1997).

Live Flesh (1997). Talk to Her (2002). (© Sony Pictures Classics; Daniel Martinez; Miguel Bacho

Talk to Her (2002). (© Sony Pictures Classics; Daniel Martinez; Miguel BachoAlmodóvar repeatedly stresses the unconscious aspects of his art. "I never make a calculated decision to do a certain film. I follow my instinct: my stories almost choose me, not the other way round." But he is quite explicit about the influence of the great Italian neorealist Roberto Rossellini on Volver. "I enjoy the transparency of neorealism. Rossellini's Journey to Italy introduced a note of almost photographic realism to movies. I like the way these strong emotions flow so naturally. That's what I wanted in Volver. I mean, I love David Lynch but the last hour of Mulholland Drive is completely absurd. I try to avoid that by filtering everything through the perceptions of the characters."

Narratively and visually, Volver is a much more classical work than that of the stylistically flamboyant Almodóvar who gave rise to the adjective "Almodóvarian," a combination of kitsch and culture. "In Volver, take the mother's ghost [played by Carmen Maura]. I wanted her to look absolutely natural. This was the hardest thing—finding camera positions where the spectator will feel that they're seeing things with their own eyes, not with mine. The simplicity comes in renouncing artifice, in avoiding shots that try to be original, or strange, by pulling in close to the action, to the actors, to their faces. Showing your formal brilliance distances the spectator."

In Volver, Cruz plays the exuberant but world-weary older sister, Raimunda, a 21st-century version of Sophia Loren at her swaggering finest. "I dedicate more time to rehearsal during preparation and preproduction than many other directors," Almodóvar says. "This gives me the time to know the actors and to address their particular strengths and weaknesses. When we get to the shoot, we must know exactly what we're going to do. In the case of Penélope, she needs a long time to connect with a character—time which isn't available to her in her English-speaking work. She's slow, visceral, hardworking. But when she does finally connect with the role, she can do wonders. Basically, I'm a director of actors."

The look of Volver represents a departure from the bright, saturated tones we have come to expect from Almodóvar. "Using color is congenital to me—but the coloring of the movies changes. A large part of a movie's aesthetics is determined during the location hunt. And the La Mancha region is suffused with a very particular light—austere blacks and grays, where the colors are dampened down. That's what I wanted to capture on this occasion. So I change palette."

An almost hyper-real clarity of image is another identifying mark of Almodóvar's work. "When I started making movies, I thought that everything could be in focus, and I was disappointed when I realized it was technically complex to do that. But I do try to use deep focus where I can—there are often things happening in the background which are driving the story along."

Considering his emphasis on control, it is surprising to hear Almodóvar admit that he doesn't understand how his cameramen achieve the effects he seeks. "I barely understand camera terminology. On Volver, I show [cinematographer] José Luis Alcaine pictures from magazines, papers, books, to suggest, say, the particular lighting of the interiors in La Mancha. We had lengthy conversations about light. Part of José Luis's talent is to understand what I'm trying to say. I tend to alter his work only on close-ups, where I want to emphasize a certain aspect of the facial landscape."

The importance of this deep understanding between director and crew means that Almodóvar's team has remained fairly constant through the years. Alcaine stopped working with him after Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! but returned to the fold with 2004's Bad Education. "I like to make changes to the crew every three films or so—it's good to renew, because otherwise things could become routine. And of course some people are better for certain movies, depending on the aesthetic." However, composer Alberto Iglesias is a constant who has worked with Almodóvar since 1995. The director refers to him as his "musical alter ego."

"I like to be 100 percent involved in terms of everything that physically appears in the films," Almodóvar says about the production design. "I'm very thorough. I have to approve every single object that appears." He brings many of them to the set himself: the clothes which Cruz wears in Volver, for example, were picked up from Madrid flea markets, just as her character would. "I'm a nightmare for my production designers, because I turn them into mere helpers."

BRIGHT IDEA: Almodóvar's use of pop culture, bold imagery and exploding colors

BRIGHT IDEA: Almodóvar's use of pop culture, bold imagery and exploding colors

come together to create the emotional power of All About My Mother. (© Sony)El Deseo, the company Almodóvar runs with his brother, Agustín, has produced his movies since 1985. It is from the stability of his production setup that his enviable artistic freedom derives. "When it comes to deciding what I include, I'm completely free—perhaps uniquely so. I'd find it hard ever to work within the Hollywood production system. That's not to say I go over budget. I just spend the time doing things the way I want to do them. I never think about what the market wants. I don't know what the market wants."

This freedom also means the ability to make changes while filming, in what Almodóvar terms the "adventure" of the shoot. "I need the freedom to change things on set, when the lights are up and the actors are ready to speak, because this is when my inspiration is at its peak. I need flexible actors at this point. Truffaut compared a shoot to a train with no brakes, and the director has to make sure that the train doesn't come off the rails. A film is a living thing—this thing is boiling over, and you have to have a thousand eyes to take it where you want it. When one of your actors suddenly does something extraordinary, you're the first to see it, you're the first witness—and for me, those moments are the miracles that make directing films the passionate activity it is."

"In the end," Almodóvar murmurs, "it's all about passion. Without the passion, directing films just wouldn't be worth it."