BY GARY GIDDINS

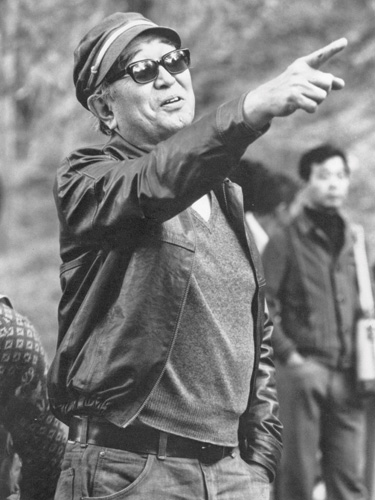

Akira Kurosawa in 1975. (Credit: MPTV.net)

Akira Kurosawa in 1975. (Credit: MPTV.net)Spectacle in American movies gets little critical respect. It is too much associated with sanctimony, bad history, inflated romance, and special effects rather than with serious ideas and epical grandeur. In the postwar years, Hollywood studios—hammered by the loss of its theaters and the rise of free-agent actors and television—fought back with spectacle as a corollary of lavishness: wider screens, longer running times, deeper cleavages, massed extras, star cameos, and colossal stories involving Christ, Moses, Rome and D-Day. Successors to Griffith and Selznick bet their dividends on the usual trifecta of piety, star power, and visual gimmicks.

Another possibility existed: humanist spectacle springing from a capacious, Homeric scrutiny of mankind. In this realm, cinematic opulence is an extension of the artist's vision, not the producer's calculation. Vision may demand a large canvas but it isn't defined by size: It is a way of seeing, as clear-eyed in the hero's tent as on the battlefield. No one better exemplifies this approach than the Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, whose influence spurred the imagination of a generation of American directors.

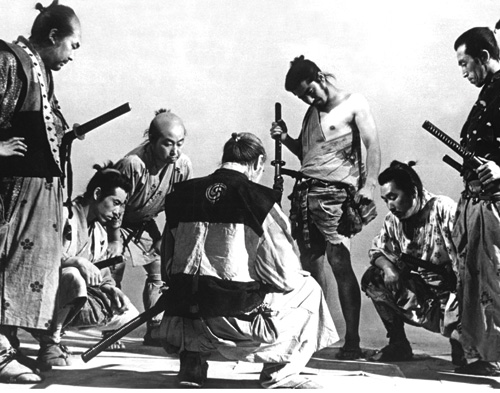

Seven Samurai (1954) (Credit: Photofest)

Seven Samurai (1954) (Credit: Photofest)

In Kurosawa's work, the Olympian view predominates, whether the subject is as large as war and kingly succession or as pitiful as modern man caught in the labyrinth of urban blight. He knows that all we need to know of Achilles is that he is proud, not how he got that way. Pride dominates the human condition, generating action; motive is conjectural, generating contemplation, which isn't nearly as cinematic. As a character is Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch says, "I don't care what you meant to do. It's what you did I don't like."

The Criterion Collection, which has released 14 Kurosawa films on DVD, now invites us to contemplate what is arguably the greatest of all action films: the endlessly imitated, never equaled 207-minute The Seven Samurai (1954), in an irresistible three-disc presentation. Only dedicated enthusiasts will access all the deep-background material, including a two-hour conversation with Kurosawa (shot in 1993), two documentaries, two critical commentaries, trailers, artwork and written essays. The prize is the restored print, a vast improvement on Criterion's previous edition: sharp blacks and whites replace worn grays, the soundtrack resonates.

Other films (including a few by Kurosawa) contain more skillfully choreographed action and sharper dialog. But none so movingly combines sweeping spectacle with the inspired delineation of character. The plot is simple enough to suit a one-line treatment (farmers hire professional warriors to defend them from marauding thieves) and the structure has two acts: recruiting the warriors, battling the thieves. Yet Seven Samurai, set in 16th-century Japan, encompasses the Homeric-Tolstoyan canvas of war and peace, honor and shame, good and evil, class warfare, gender inequity, generational fear and changing times. Its comedy ripens in the quotidian interaction of social opposites.

If a great epic must focus more on observation than psychology, the psychology it does present must be so astutely drawn that little explanation is required. Kurosawa found precisely the technology to serve that vision: multiple cameras and a telephoto lens. Shooting action sequences with three cameras guaranteed him full coverage without having to shoot and match different takes. The telephoto lens enabled him to stay out of the actors' way while creating an absolute omniscience; the narrator looks from on high, yet can zoom in for the kill. Kurosawa's mastery is always at the service of characters—in Seven Samurai they are highly individualized samurai and farmers whom we revisit with increased pleasure and understanding.

Rashoman (1950) (Credit: Criterion Collection)

Rashoman (1950) (Credit: Criterion Collection)

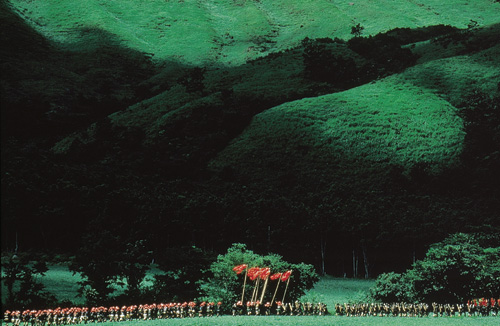

Ran (1985) (Credit: Criterion Collection)

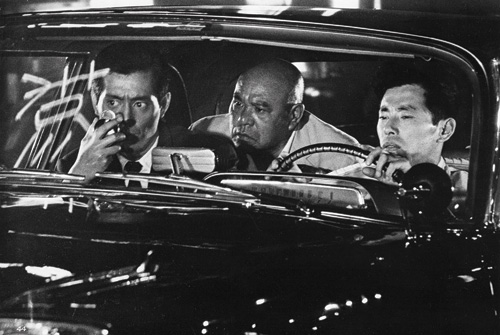

High and Low (1963) (Credit: Photofest)

Ikiru (1985) (Credit: Photofest)

Looking back after half a century, during which the proliferation of samurai and other martial arts films have achieved a virtuoso athleticism, we can't help but notice that swordsmanship in Seven Samurai is relatively inexpert. Yet in what other film do we come to love its ancient warriors? When Kurosawa's samurai novice stares worshipfully at the reticent master, Kyuzo (played with reclusive cool by Seiji Miyaguchi), we smile at his naiveté—and share in it. Kyuzo's professional bravura (which inspired James Coburn's knife-thrower in John Sturges' 1960 non-epical rehash, The Magnificent Seven) is as appealing as it is deadly.

Kurosawa's most steadfast actors, Toshirô Mifune and Takashi Shimura, have defining roles in Seven Samurai, embodying opposing tonalities of the spectacle—Mifune an obstreperous trumpet, Shimura a shrewd oboe. Their respective expressions of blowhard irreverence and wise assurance mandate the film's shifting tempo and display Kurosawa's masterly economy. We learn all we need to know about their characters in emblematic moments. Mark Twain once observed, "Action speaks louder than words but not nearly as often." He would have no complaints about Seven Samurai, in which Mifune discloses his secretly humble origins in four words: "This baby is me!" he says of a farmer's infant, handed to him by its dying mother. No less economical is Kurosawa's comment on the mounting impersonality of warfare. His samurai are cut down by muskets, a weapon they aren't trained to resist.

In the 1950s, Japan was perhaps the least likely country to revive cinematic spectacle as an empowering art. Hollywood had the wealth and technical means; the Soviet Union had the panoramic tradition of Eisenstein. Japan, digging itself from the rubble of firebombing and nuclear attacks, was known for a cinema of domestic realism—most notably the chamber films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. In claiming the 16th century as an adaptable setting for his themes, Kurosawa restored a forgotten age to Japanese history and gave the West a novel reflection of itself.

Kurosawa (1910-98) had single-handedly internationalized Japanese cinema with his 11th film, Rashômon, in 1950. Based on stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, whose use of the distant past anticipated Kurosawa's, it is a fiercely stylized film that combines Noh Theater with startling camerawork and lighting: the sunlight-dappled forest and the rushing of foreground characters against the far horizon became Kurosawa trademarks. In the West, the film seemed obviously Japanese; in Japan, Kurosawa's vitality and violence seemed all too Western. Over time, he was criticized in both hemispheres for his alleged lack of authenticity.

Indeed, he often looked west for material, conceding the influence of Griffith and Ford, and adapting Shakespeare three times (Macbeth as Throne of Blood, Hamlet as The Bad Sleep Well, King Lear as Ran), as well as Gorki (The Lower Depths), Dostoyevsky (The Idiot), Ed McBain (High and Low) and Dashiell Hammett (unacknowledged for Yojimbo). He switched between films set in the past and present day, including cycles of films dealing with the medical world and industrialism (the two come together in High and Low). Yet most of his films derive from Japanese sources, and all of them suit his thematic concerns and objective visual style, predicated on a love of spectacle.

For Kurosawa, history is a cycle of violence and corruption, interrupted by rare heroic figures who stem the tide and give cause for hope. The circularity of his vision is echoed by the shape of his career: the masterworks of his late period replay ideas found in the two dark stories that triggered Rashômon. The allure of his seven samurai warriors sours by the time of Yojimbo (1961), and vanishes from the radiantly colored yet desolate landscapes of Kagemusha (1980) and the awesome Ran (1985).

Ran, which is as much a critique of Lear as an adaptation of its central dilemma, set again in the 16th century, may be Kurosawa's supreme masterpiece. (Ran is packaged in a stunning two-disc set and features one of the most eye-popping transfers in Criterion's catalogue.) We marvel at the ingenuity of his widescreen compositions, saturated color, and rousing dramatic peaks, notwithstanding the copious bloodletting and severe denouement. Yet we expect spectacle and grandeur in this kind of film. Those qualities are more surprising and disturbing when found in the corrupt mire of contemporary Tokyo. In that sense, Kurosawa's modern films are among the purest expressions of his humanism, particularly Ikiru (1952), his meditation on a dying bureaucrat and one of the few great films (another is Leo McCarey's neglected Make Way for Tomorrow) about aging and death; and High and Low (1963), a thriller in which a moral quandary (should an executive ruin himself to ransom the mistakenly kidnapped son of his chauffeur) triggers a grim study of class division and irrational hatred. (The Criterion DVD of High and Low could stand to be refurbished; the widescreen frame seems minutely cut off on both sides, and there are no extras.)

Kurosawa's unfashionable preference for action over motive did not sit well in the early 1960s, the height of the empathetic Nouvelle Vague. Rarely did an epical vision free of sentimental pandering make its way into American films, although there were some: Anthony Mann's El Cid, Orson Welles's Chimes at Midnight and Stanley Kubrick's 2001 come to mind. Yet a decade later, Kurosawa's ability to locate the grand manner in ordinary and extraordinary lives found an enthusiastic reception among young American directors. Without his example, it's hard to imagine such prodigious testaments as Francis Coppola's The Godfather, Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull, Philip Kaufman's The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List. One measure of a towering artist is that he makes other artists raise their sights.

Gary Giddins won a National Book Critics Circle Award for Visions of Jazz and a Ralph J. Gleason Award for Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams. He has written biographies of Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker, which were the basis of documentaries he directed for PBS. His essays on movies, music and books were recently collected in Natural Selection (Oxford University Press).