BY STEVE POND

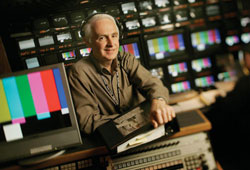

HERE SHE IS: Stage manager Gary Natoli directs traffic at the

HERE SHE IS: Stage manager Gary Natoli directs traffic at the

Miss America Pageant. (Credit: AP Images)

They all say the same thing: it's the adrenaline. It's the tension, the excitement, the knowledge that once that countdown starts, there's no turning back, no reshoots, no time to fix it in post. Forget about second takes; there isn't even time for second thoughts.

This is the world of live event television, of the Oscars and Grammys and Emmys, of beauty pageants and inaugural galas. And on the front line at every one of these events is a small, tightly knit group. They're the associate directors and stage managers who count down cues and wrangle celebrities, making sure that the trains run on time in an environment where one snafu can derail everything.

And to a man, and woman, they don't love the job in spite of the fact that it's tense and nerve-wracking; they love it because it's tense and nerve-wracking. "It's the best high in the world," says Kathleen Fortine, an associate director who has been working live shows for 15 years (a tenure that makes her a relative newcomer to the field). "If I had to sit in an editing room and hear a producer say, 'Let's go two frames that way,' or if I had to take three hours on one setup, I would kill myself. Live is the only way to go."

Stage manager Gary Natoli proposes an equation. "Take the stress an average person experiences in a week, condense it into one day, and multiply it by ten," he says. "That's what we deal with in an average fourteen-hour day."

Natoli is not complaining when he says this. "I love that people can walk the wrong way or say something inappropriate, or scenery can fall over, and you have to adjust," he says. "That's the beauty of live TV."

It is, perhaps, an environment that attracts a certain breed. Their numbers are limited: maybe thirty stage managers in Los Angeles get calls for the big shows, fewer on the East Coast, while the numbers of top associate directors is even smaller. "It's a very small, tight group of very good friends," says Lynn Finkel, who moved into stage managing after working on staff at Radio City Music Hall in New York.

Associate directors, as many as eight or ten on the biggest shows, cover a wide spectrum of duties, from the 1st AD who serves as the director's right-hand aide to specialized staffers handling video screens, audience shots, red carpet arrivals, pre-taped packages, voiceovers and every other facet that needs to be cued or commanded from the control truck.

Stage managers operate in a different arena, shepherding talent on and off stage, watching over the host, working with stand-ins, and supervising every change of scenery (and, essentially, everything else) that needs to happen onstage.

"Like any high-pressure job, you really end up trusting the people you work with," says Christine Clark Bradley, an AD for twenty years. "It's all about flow, about getting in the zone, and the ADs and stage managers have to get in that zone together. There's a huge connection between the truck and the stage, between the AD and the stage manager."

Getting in the flow means making sure that the stagehands make their set changes smoothly, that the presenters and performers hit their marks and read their lines, that the cameramen are ready to shoot the right reaction shots to every joke and acceptance speech. But that part of the job–the part that's been meticulously planned, plotted, timed and rehearsed–is not what enamors those who do it. The other moments–the times when things don't go the way they went in rehearsal, when you've suddenly got to improvise–are the moments that each AD and SM indelibly remembers.

They remember the Grammy show where rapper Ol' Dirty Bastard decided to take the stage and talk about how he'd been robbed of the award he deserved, even though Shawn Colvin was on her way to the podium to accept the Grammy. Natoli told Colvin to hang on, went over to ODB and muttered, "Okay, that's enough," and hustled him offstage. "He got it," says Natoli. "He knew he wasn't supposed to be there."

THE WINNER IS... Stage manager Dency Nelson explains the

THE WINNER IS... Stage manager Dency Nelson explains the

ropes to John Travolta at an Oscar rehersal.

Garry Hood with Jack Nicholson before an Oscar telecast.

(Credits: Art Streiber)

They remember David Letterman pulling Dency Nelson aside an hour before the 67th Oscar telecast, and running a new joke by the stage manager with whom he'd had a long working relationship. After assuring Letterman that the gag was funny, Nelson quickly notified the truck: during the host's monologue, he told them, they'd better have cameras ready to shoot reaction shots of Uma Thurman and Oprah Winfrey.

They remember the Jim Thorpe Pro Sports Awards when a fire in ABC's New York studio shut down the control room from which commercials were run. When the control room came back up mid-show, the crew had to re-format the entire show on the fly, adding commercial breaks where none had existed to frantically squeeze in the ads that had already been paid for. "We were making it up as we went along," AD Jim Tanker says, "and telling everybody, 'This is not on your rundown, guys!'"

They remember the Soul Train Music Awards at the cavernous Shrine Auditorium–where, says Fortine, a major cancellation happened fifteen minutes to airtime. "I had to run all the way across the Shrine to producer Don Cornelius' office, tell him, get a decision from him on what to do, change the order of all the presenters, and tell everybody the new order during each commercial break," she says.

They remember the Grammy Awards show when a few hours prior to showtime, Luciano Pavarotti announced that he was too sick to sing the aria "Nessun Dorma." "Ed Greene, the audio man, said that Aretha Franklin had done the same aria on a MusicCares benefit two nights earlier," says Bradley, "so we grabbed her to take his place."

They remember Julia Roberts deciding, in the middle of the 76th Oscar show, that she didn't want to walk down the staircase that was about to be placed on the Kodak Theater stage for her entrance. Roberts told Nelson, who radioed producer Joe Roth, who agreed to a simpler, easier entrance; with minutes to spare, the ADs and SMs scrapped the staircase and readied an entirely new entrance for the star.

The stories are legion, and everyone who works in live television has the battle-scars and the pride that go with them. "When you shoot a death-defying stunt for a feature film, you can put twenty cameras on it, and rehearse it for weeks on end," says Jeffry Gitter, who has worked live television as both a stage manager and an associate director. "And god forbid something goes wrong, but if it does you can shoot the stunt again, given the time and money. You may want to do it one time and one time only, but you still have that opportunity. In live TV, you have no second chance."

So what does it take to handle the pressure and do the job? We asked a variety of ADs and SMs, and got a variety of answers that boiled down to a simple formula: be prepared, be calm, move fast and don't look back. Among their suggestions:

AD LIBBING: Jim Takner often has to improvise in the control room.

AD LIBBING: Jim Takner often has to improvise in the control room.

CAPITOL JOB: (left to right) Lynn Finkel, Jeffry Gitter, Arthur

Lewis, Garry Hood and Dean Gordon in Washington DC

working the National Memorial Day Concert, 2005.

Know your job... and everybody else's: "You really have to know how all the people and the departments work together and fit together," says Garry Hood, a Nashville-based stage manager who has worked close to two dozen Oscar and Grammy shows, most as the head stage manager. "That's the single most important thing."

Expect the worst: "You have to go through a complete pre-production process, with plans for every possible contingency," says Tanker, 1st AD on the past ten Oscar shows. "You play an analytical game with all the what if's."

The rule is simple: if something can go wrong, at some point, it probably will. "You'll lose all the graphics that are supposed to be onscreen, and I'll be sitting there cuing things that aren't happening," says Bradley. "Or we'll lose the brains of the switcher, so we can't do dissolves or fades... Anything you can think of that might happen, has happened. And you have to know exactly what to do when it does."

Be a people person: This holds particularly for stage managers who work with talent, who need to guide big stars accustomed to multiple takes through the tension of doing it live and doing it once. "They walk into the wings at the Oscars a little nervous, and when they see me, I see a lightening of the load and a smile," says Dency Nelson. "I'm the last person they see before they go onstage, and I want them to go out with their full palette of colors."

Which is not to say that getting along with Tom Hanks, Russell Crowe, Julia Roberts and Barbra Streisand is the only time that people skills come into play. After all, those huge scenic pieces aren't going anywhere without a lot of help from a batch of overworked stagehands. "You have to have a rapport with the crew," says Nelson, "which is a whole different thing than it takes with the stars. The crew will not suffer fools and newbies, and you have to get their respect."

Know how to listen: "The first show I did, I put my headset on, and I could not understand how on earth you could decipher what was important," says stage manager Lynn Finkel. "The AD was counting out cues, the director was talking to people, there was a separate ISO channel for the ten stage managers. I thought, there's no way I can figure out what's important in all this chatter."

Know how to speak: And since everybody's headsets are filled with a constant barrage of info, you have to say what you need to say without contributing to the babble. "With some ADs, everything's a sentence, everything's a paragraph," says Fortine. "And that doesn't work. You've got to speak quickly and succinctly. You say, 'Close-up on two!' Not, 'Camera two, could you move in for a close-up?'"

And remember who's boss: "The most important thing," says Bradley, "is to make sure you're in sync with the director." The director sets the tone and shares ultimate accountability with the producer; the AD/SM crew is there to do what he wants as soon as he wants it, if not before.

"You have to know what the director is thinking," says Tanker. "You have to not say too much, but not say too little, either. You don't get in the way of his cadences, but you draw his attention to certain things he needs to see." After ten years working the Oscars next to director Louis J. Horvitz, Tanker has great latitude in cuing music, scenic changes and announcer voiceovers. "That frees him to concentrate on telling the story," Tanker says. "And at the end of the day, the director is the storyteller. It's our job to take care of everything else, so he can tell the story."

The job has gotten trickier over the years: schedules are tighter than they used to be, stars are reluctant to come in ahead of time to rehearse, and the technological advances of digital and high-definition bring their own complications. The shows themselves, meanwhile, just keep getting bigger: the Grammys, which long ago moved into 20,000-seat arenas with multiple stages, can require as many as twenty stage managers and ten associate directors, while MTV relentlessly ups the ante with the extravagances of its Video Music Awards.

"Every year with the VMAs, we look at what they want to do and say, it can't be done," says Gitter. "And inevitably, it gets done."

Which means they have to do it again, but bigger, the next time around. "They keep throwing these massive shows at us," says Finkel, "and the problem is that we keep pulling it off."

That they do so without fanfare is a source of pride. "I like being the unsung hero," says Nelson. "Anytime the process becomes about us, we're not doing our job. We are facilitators to make things easy for other people to do their jobs."

That's not to say that they don't occasionally wind up in the spotlight–but for the most part, these are men and women who take that spotlight reluctantly. "I don't like being on camera," says Garry Hood. "If I need to go out there and hand somebody a microphone, I'll tell the director, 'Go to a close-up, I'm going in.'" He remembers one particularly artful mid-number handoff at the Tonys, where he dashed onstage and replaced Martin Short's malfunctioning mike without being caught on camera.

"After the show," Hood says, "I was at a party, and [producer] Pierre Cossette called me over and said, 'Hey, kid! What you did tonight, you're the best thing I saw on Broadway all year.' To me, that was the ultimate compliment."