BY ANN FARMER

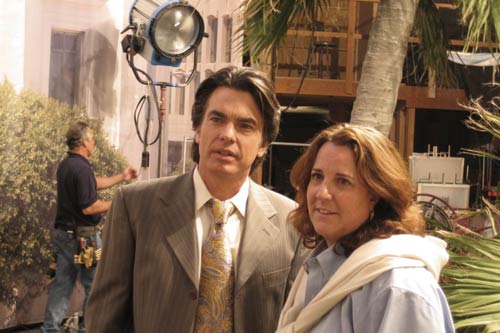

The OC - ©2006 Warner Bros. Ent. Inc. The OC - ©2006 Warner Bros. Ent. Inc. |

Lisa Cochran, UPM Lisa Cochran, UPM |

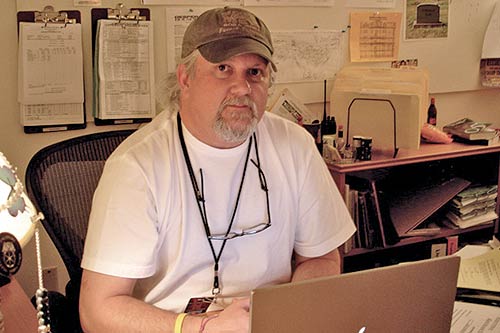

The District - ©CBS/Landov The District - ©CBS/Landov |

Cleve Landsberg, UPM Cleve Landsberg, UPM |

Six Feet Under - photo John P. Johnson/HBO Six Feet Under - photo John P. Johnson/HBO |

Robert Del Valle, UPM Robert Del Valle, UPM |

Joan of Arcadia - photo ©CBS/Landov. Joan of Arcadia - photo ©CBS/Landov. |

Herb Adelman, UPM Herb Adelman, UPM |

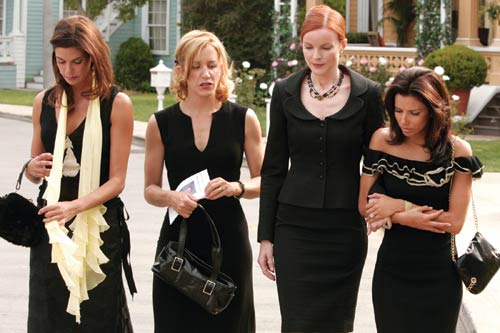

Desperate Housewives - photo ©2006 ABC Desperate Housewives - photo ©2006 ABC |

Charlie Skouras, UPM Charlie Skouras, UPM |

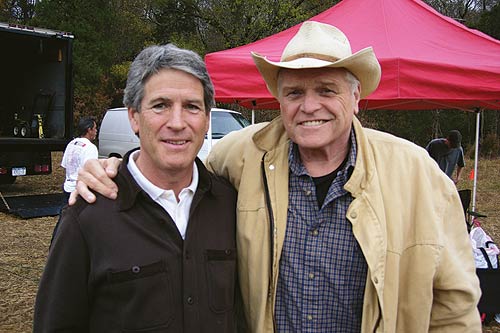

Boston Legal - photo ©2006 ABC Boston Legal - photo ©2006 ABC |

Janet Knudsen, UPM Janet Knudsen, UPM |

Law & Order: Criminal Intent - ©2006 NBC Law & Order: Criminal Intent - ©2006 NBC |

Mary Rae Thewlis, UPM Mary Rae Thewlis, UPM |

Being a Unit Production Manager used to mean always having to say no. "Then it was easy," says Charlie Skouras, UPM on the ABC hit Desperate Housewives, referring to the '80s, when being tightfisted was standard operating procedure for most television UPMs. "The answer was always no," he says, recalling that many of his early projects–for which he managed the purse strings–basically ran by the seat of their pants. "We just didn't have it. We'd have problems affording a shooting permit or a policeman."

All that changed once cable splintered into a mind-numbing array of choices for viewers, including sleek, expensive dramatic episodic television shows like HBO's The Sopranos, which reportedly costs more than $2.5 million an episode to produce. Network television was forced to ratchet up its production values in order to successfully compete. "I'm glad those days are over," says Skouras, who is thoroughly enjoying the more complex challenges involved in making Desperate Housewives a household name. "That's not to say it's easier," he adds. "It's just a different set of problems. Now there's more juggling and being creative."

Even as things have progressed qualitatively on dramatic episodic television, the most basic responsibilities of UPMs have stayed the same–preparing the production budgets and shooting schedules, finding locations, negotiating with actors and vendors, hiring crew and signing checks. And they continue to oversee all the other nitty-gritty aspects of day-to-day operations, including shifting locations when the weather acts up or lending a friendly ear when a crewmember has a gripe.

"It's not just crunching the numbers," says Herb Adelman, a veteran UPM whose two most recent projects are the CBS series Criminal Minds and Joan of Arcadia. "You have to be able to get along well with people. You need a fairly calm personality and a mastery of details. And be good at problem solving."

Still, those problems used to be simpler. "Ten years ago, no one used visual effects in television, and it was a one camera crew versus the two camera crews of today," says Adelman. He recalls that for his first Assistant Director job in 1982 on the NBC hit dramatic episodic television program, Hill Street Blues, "we were able to knock out an episode in seven days versus the eight days it typically takes today."

"Shows are just bigger," says Robert Del Valle, who worked as UPM on all five seasons of the acclaimed HBO series Six Feet Under that mimics films with its feature-like action sequences, sophisticated sets, special effects, and ambitious storylines. Accomplishing all of this requires additional departments, setups, scenes, props, larger crews and the latest tools in television technology. "As the UPM, you have to manage all these elements while protecting the director's creative vision," says Del Valle, who is currently writing a book titled The Basics of Episodic Television Production.

"My phone never stops ringing," says Mary Rae Thewlis, UPM on NBC's Law & Order: Criminal Intent, explaining that her involvement with each new season begins at the pre-production stage and doesn't end until the last set has been taken down and stored. While shooting, she divides her time between the production office and the set–beginning early in the morning and ending late. "I try to keep [the schedule] to 12 or 13 hours a day," she says, adding that it helps to have a very understanding spouse or significant other when spending long days on the set.

Bigger budgets also bring bigger fires to put out. "I can spend eight days prepping an episode and it can still unravel. That's frustrating," says Lisa Cochran, UPM for Fox's The O.C. Recently, the show was set to shoot a party scene on a beach in L.A. until storms blew in and battered the beaches so badly Cochran was forced to relocate the cast and crew to a beach in Northern California. "It's out of your control. But someone has to fix it," says Cochran, who also had arranged for the cast and crew to go to New Orleans this year to shoot its annual spring break show, until Hurricane Katrina hit. "Obviously, we've had to scramble," she adds.

"Problems tend to come late at night or early in the morning, and always in the cold of winter," says Thewlis, describing how a recent Law & Order script called for a woman's body to be dropped from an airplane into the chilly waters off Far Rockaway, New York. Substituting a male stunt actor who was bundled in a thick, wool African coat (a clue in the storyline), the crew and cast shivered as the bulky coat kept forcing the actor's body to bob to the surface too quickly, forcing take after take.

"We say, 'What a way to earn a living: standing on a beach in 17 degree weather, trying to get someone to stay underwater long enough,'" laughs Thewlis, who suggests that managing an ambitious television production is not for anyone who panics easily or gets overwhelmed at the prospect of juggling 25 balls at once. "A sense of humor is way up there," she adds.

One of the most challenging aspects of the UPM's job is their tightrope walk between the director's team and the producers' camp. "Production managers have two masters," says Skouras, explaining that UPMs are given a finite amount of money by the studio to finance and support the creative vision of the director.

"We're given a bottom line," says Skouras. "We have to deliver what's written, but also do it for budget," noting that UPMs must ultimately answer to the studio. He says there are advantages to working on such a successful show as Desperate Housewives. "We're not under the microscope as much." However, as UPM, it remains his job to monitor the daily production costs and make certain tough decisions on where to draw the line. "Especially if we want a sequence that's elaborate with stunts or requires tons of extras," says Skouras. "Or if we need to shut down a department store: That costs money."

Skouras works hard at being viewed as a conduit between the two camps, rather than the holder of the reins. "I'm the one who says yea or nay," he says, "but I try to say it as nicely as possible and listen to their problems."

But no matter how sensitive their approach, most UPMs eventually butt heads with their directors over issues that pit the budget against the creative, from time-to-time triggering adversarial feelings. "Some UPMs feel some directors are unreasonable," says Del Valle. On the other hand, he adds, "Some directors feel that UPMs are there to say no; that they're not as much a part of the director's team."

Rick Wallace, who is currently directing episodes of ABC's Commander in Chief, says when he was just starting out as a freelance director he routinely pushed hard for his creative ideas, even at the risk of alienating the UPM. He says experience has taught him differently. "It's always better to forge an effective creative relationship with the UPM," he says, explaining that while it's important for the UPM to be able to share the director's creative vision, it's equally important for the director to appreciate the UPM's function and responsibility to the studio. "If you want to come back, you have to work collaboratively within the financial and creative boundaries of the particular show." Otherwise, he warns, "You don't get invited back."

During initial story meetings for ABC's Boston Legal, for example, the writer, director, assistant director, producers and the UPM lay out the groundwork together. "Everybody looks at the script and marks their concerns," says UPM Janet Knutsen, explaining that it provides directors their first good opportunity to verbalize what elements are necessary to pull it off. Knutsen will often crunch the numbers. "We weigh what's important," she says. "What ultimately will hold trump is, does the story work without going over budget?"

Once the shoot begins, the director sometimes comes up with further ideas that require greater resources than the budget allows. It then becomes critical for the UPM to determine if the request can be carried out within the show's financial limitations. Knutsen, for instance, suggested that a scene her director wanted to shoot on location could be effectively done on a stage set, saving the additional expense.

On the other hand, when she received a last minute request for an item she describes as a Victorian-era "hysteria machine," complete with levers, pulleys and the ability to create steam, she recognized that the prop was integral to the director's vision even though it blew the roof off the budget. "We really needed it," she says, explaining how she instructed the prop master to shop the job out until they secured a bid that she could finesse.

"All our efforts are to tell a good story," says Thewlis, explaining how important it is for UPMs to be able to shoot from the hip. For instance, she happened to be on the set when the script called for an actor to wriggle through the window of a Bronx bar, and he couldn't fit. She spotted a stunt man who looked like a good match and suggested having him wigged up and substituted, thus keeping the production on schedule.

The more savvy UPMs are also thinking ahead. Knutsen says she's been getting more bang for the buck this season by shooting two episodes simultaneously, moving the actors and crew back and forth between two stages as needed.

Cochran says she is always looking to squirrel away a little play money, for say, sweeps week, "when we'd like to go bigger." So she routinely suggests cost-cutting measures, such as taking down a set that she thinks is too expensive to maintain.

"A lot centers around the UPM and how they approach their job," says Michael Fresco, a freelance director who has worked with Cochran on a number of episodes of The O.C. over the last three seasons. While acknowledging the difficult position of the UPM, he says the positive attitude that Cochran always brings to the table helps foster a strong sense of teamwork. "She makes us feel that we're all on the same side," he adds, "it makes everyone much more apt to work with her."

The DGA also works actively to strengthen the relationship between directors and UPMs by sponsoring committees and events that encourage an open dialogue between the two positions. Cleve Landsberg, a UPM in film and television (CBS' The District), currently chairs the AD/UPM Council West and is the former co-chair of the Director-UPM Committee. "It is important for UPMs and directors to have an opportunity to talk about the process and learn more about each other," he says. "After all, at the end of the day, the two positions have to work together so that collaboratively we can come up with the best results."

Mary Rae Thewlis and location manager Tom Ross on the Law & Order set.

Mary Rae Thewlis and location manager Tom Ross on the Law & Order set.

Charlie Skouras where he does 90% of his work.

Lisa Cochran on The O.C. with cast member Peter Gallagher.

Janet Knutsen chatting with AD Bruce Humphrey on The Practice.

Cleve Landsberg on a film set with actor Brian Dennehy.

Robert Del Valle (on slab) on the Six Feet Under set.

Herb Adelman with director Glorio Munzio on Criminal Minds .

Several UPMs point to their training as Assistant Directors as particularly important. Del Valle, Thewlis, and Adelman, all graduates of the DGA Assistant Director Training Program, say it provided them with a great foundation. "By the time you finish it, you know every step of the process," notes Thewlis. Trainees start out as 2nd ADs on actual television and film productions. Once they advance to the position of 1st AD, their job is to track a project's progress from morning till night, shuttling scheduling concerns between the director and the UPM, who is ultimately responsible for keeping things on target.

In fact, scheduling is so closely associated with the job, that when Knutsen enters a set, she has humorously noted that, "the directors look at their watches, like, 'am I going too slow?'"

During his tenure as an apprentice 2nd AD, working mainly on movies for television, Adelman says he learned what kind of pace the crew is capable of keeping. "You see what it's like to shoot an all night scene, in the rain: The crew gets tired and grumpy." Those lessons have helped him throughout the years, particularly when a production starts falling behind schedule and he has to decide whether it makes more economic sense to keep going or finish up the following workday.

The apprenticeship also provided him the opportunity to see first-hand how a director thinks and what he or she needs to tell the story. And it prepared him for the task of budgeting a script. In other words, says Adelman, "to look at a scene and know what equipment is needed, how much it will cost and how long it will take to make."

When a script comes in late, however, it makes it that much harder for a UPM to be fiscally responsible. "It can create a train wreck," says Del Valle, pointing out that in addition to the financial considerations, tardy scripts give directors less time to cast and prep the scenes, which in turn puts pressure on everyone else associated with the project.

Four years ago, the DGA launched a campaign to curtail the growing problem of late script delivery in episodic television. Some of those writers singled out as the worst offenders claimed they were having a harder time meeting deadlines because of network demands for more sophisticated fare. Recent studies indicate that the problem may be improving. Directors like Michael Fresco say they've seen a noticeable difference. "It's been effective," he says.

But even if a script shows up late, the UPM must "step up to the plate," says Adelman, who after decades in episodic television, has watched it evolve from a smaller, more personal industry–where he could do business on a handshake–to a more corporate structure. But even as things have changed, the best challenges of his job have remained the same. "It's the problem solving," he says. "Figuring out how you're going to shoot it. Using your imagination day in and day out. It's like going to play every day."