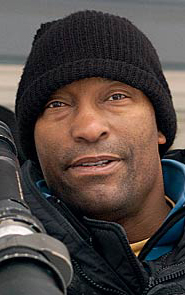

BY HENRY SHEEHAN

SHARK ATTACK: "No one had done

SHARK ATTACK: "No one had done

a movie like this before," says John

Singleton about Spielberg's Jaws.

(Credit: Paramount Pictures)

John Singleton is rocking back and forth in his seat in delight. "Look at all that blood!" he points out with a laugh, pointing at a screen where poor Robert Shaw is getting bitten in half by a giant great white shark. "Hear it? Grrrrr! Rooaaarrr!"

The filmmaker, who in 1991 became the youngest person ever to earn a best director Oscar nomination, is truly reliving a moment from his childhood. As a kid, he saw Jaws under what might have been optimum conditions for its time (1974): At a drive-in theater, specifically the Vineland Drive-In, a pastel outpost in the grungy City of Industry (now the only operating open-air cinema in Los Angeles County).

But Singleton's exclamations aren't just a flash from his youth. He's also analyzing the use of sound by another young filmmaker, Steven Spielberg, who was only 26 at the time he made Jaws. As Singleton points out, sharks don't growl, but Spielberg had cleverly mixed down the threatening, animalistic rumbles into the soundtrack's orchestrated cacophony of music, splashing, and human shouting. The result might have been zoologically wrong, but cinematically oh-so right.

"It was the first Spielberg movie I ever saw and I remember just being so intrigued by how great the movie was," Singleton says, viewing the film again in a DGA screening room. "Later on, when I was 9 years old and Close Encounters came out, I recognized the name of the guy who did it. I saw him on [ABC newsmagazine] 20-20 directing Close Encounters and I was like, 'Wow, I want to be a director.' What I loved about Jaws was that he really told the story with the camera. You know, it's not like filmmakers now where every movie they make is from another movie. No one had done a movie like this up till then. It's just the sustained tension of it, the excitement of it, and the pure voyeuristic pleasure of it."

The tale of a marauding shark snacking on the inhabitants of an East Coast vacation colony may seem an odd choice for Singleton to point to as a crucial influence on his own work. His debut, Boyz N the Hood, set an example for films to come, works embracing open engagement with African American themes and settings, a preoccupation with relationships between fathers (or father-figures) and sons, and frequent threats–even occasional outbursts–of tragic violence.

RUN FOR YOUR LIFE: Spielberg's use of background and foreground

RUN FOR YOUR LIFE: Spielberg's use of background and foreground

action as kids flee the water. (Credit: Universal Studios)

That may be to undersell, though, the pervasive influence Jaws had on the cinematic culture at-large. Spielberg's megahit was instantly recognized for the directorial playground it was, an exaltation of imaginative technique over a humdrum monster story with a smattering of character bits. But not playfulness devoid of intellectual intention. It's that youthful combination of thoughtfulness and virtuosity that is, for Singleton, the hallmark of the film.

"There's simultaneous action, there's foreground action, and background action that happens in this picture and I do that a lot," he says. "Then you can play with that back and forth. I learned that from watching this movie over and over again: Moving the camera for the sake of moving the story forward. I'm 38 now, my first movie was 16 years ago, and I've realized that a lot of young filmmakers move the camera just for the sake of moving the camera. Or they're afraid to move the camera. The filmmakers I always admire, they move the camera to tell the story. Everything is in service of telling the story. It's like set-up and then pay-off. You can do that within the shot and within a sequence."

Singleton finds an example right in the film's opening minutes. The film's famed midnight skinny-dipper has already suffered her ghoulish fate and Amity Island Police Chief Brody (Roy Scheider), has been summoned the next morning to check on her still mysterious disappearance. A sequence begins with Scheider and the victim's boyfriend walking along the top of a sand dune in a mid-long shot.

"This master shot starts with a tracking shot," Singleton points out as the camera discreetly tracks along with the two characters, taking in the solitary, lonely dune. "There's choreography with the camera as they come up towards it [a 180 degree pan] and then it continues to track [this time with an open expanse of beach and ocean]. You're getting so much visual information with minimal amount of coverage and then, boom, the cut [to another shot.]"

Having noted a pattern of two-shots with mostly wide-open backdrops, Singleton analyzes how Spielberg soon cuts to a reverse of Brody and the young man now approaching the camera from a distance.

"Show me the way to go home": Robert Shaw, Roy Scheider and Richard

"Show me the way to go home": Robert Shaw, Roy Scheider and Richard

Dreyfuss are men on a mission in Spielberg's Jaws. (Credit: Universal Studios)

"Then another upset cop drops right into the frame's foreground and, boom, the music changes. You don't see what he sees, and the other two stop, they're still far away, and then Brody comes into the foreground–see, the foreground and background. Then, all of a sudden, it cuts to a close-up of the hand and the crabs all over the hand. Then a cut to Brody; the camera's still not all the way up on his face, but you get his grief, you get his emotion. He looks over to the ocean. If the camera was in a close-up you wouldn't get the fact that he looked over the ocean like, 'What is in there?'"

A close look at Boyz N the Hood instantly reveals how the director employed what he learned from Jaws. The movie's opening, in particular, consists of a series of long tracking shots that introduce the characters and their social milieu. The film's hero, a kid named Tré, shown at ages 10 and 17 (when he's played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.), often finds himself cosseted by the safety of the foreground, but confronted by emerging figures in the background. These figures can turn out to be friendly, hostile or even fatal, but this visual tension, especially during the first half, is the movie's dominant motif.

The relationships between Jaws and Boyz can be surprisingly sharp once you're attuned to Singleton's source of influence. He becomes particularly excited in his play-by-play when Quint, the salty dog played by Robert Shaw, is introduced during a meeting of Amity's alarmed politicos and merchants. The whole scene takes place in a commandeered schoolroom.

Spielberg shoots the sequence with a long, focus-shifting dolly shot through the tiny throng before, in perfect sync, ending up with a loose, but precise, close medium shot on Quint. Quint then famously gets everyone's attention by scratching his fingers on a blackboard. Even without the typically flamboyant stylistic flourish, Spielberg was clearly building tension through the use of shifting fields of action.

!["Cage goes in the water, you go in the water. Shark's in the water. Our shark. [sings] Farewell and adieu to you, fair Spanish ladies...](~/media/Images/DGAQ%20Article%20Images/0601%20Spring%202006/screeningRoom_Jaws03%20jpg.ashx?w=340&h=227&as=1&hash=5C5D38427C25B099CF6EA997C002E6453062E9AC) "Cage goes in the water, you go in the water. Shark's in the water. Our shark.

"Cage goes in the water, you go in the water. Shark's in the water. Our shark.

[sings] Farewell and adieu to you, fair Spanish ladies ..." Dreyfuss confronts

his nemesis in Spielberg's Jaws. (Credit: Universal Studios)

"Look at this, see?" Singleton says, gesturing at the beginning of a shot that encompasses nearly the entire scene. "The speaker's in the close background but it's a good composition." Working up a head of steam, Singleton's specific and general observations now collide and careen. "The thing about it is, a lot of filmmakers don't readily, even when they're planning the camera, they're not thinking pictorially in a thematic way, in the way that they're setting up. Look at that! Hear the sound? And you haven't even seen Quint. I love this. 'You all know me, you all know how I earn a living.' Robert Shaw's across the room. Then look, someone tells him to sit up. See how he looks around?"

Oddly–or perhaps logically–Boyz also has an early classroom scene set up in much the way Spielberg did his. There are virtually no close-ups. "It's easier to shoot this way because you're being economical with the time," Singleton says, describing his method of working as much as possible with long, usually mobile shots. "The thing is, you have to work out the choreography. Then you can shoot a whole master shot. If the first part of the master is good, and the second part not good, a cutaway allows you to use the first part of the shot with the second part of the master from another take."

"What I love about Steven's work is he still does set-up, pay-off–the basic filmic elements that tell a story, and not the pyrotechnics or whatever," Singleton says with eyes firmly fixed on the screen. "Still does it now. That's filmmaking. That's telling a story with pictures. One thing I've learned from watching Jaws is that the audience is exactly involved with watching the movie. Watching the movie is a participatory act. It's not a passive act. Depending if you shoot in a certain way, the audience is either laid back or they're sitting up in their seats in rapt attention. And that's what I've tried to do with my work: Try to find ways in which scenes or sequences capture the audience in such a way that emotionally, suspense-wise, they're at rapt attention."

Even a cursory comparison of Spielberg's and Singleton's films reveals another point of comparison: Both deal with, either directly or indirectly, the role and influence of the father. But Singleton demurs when it's suggested this is another lesson he learned form Spielberg.

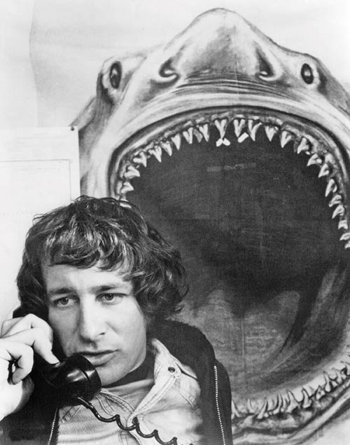

Spielberg was just 26 when he made Jaws, capturing

Spielberg was just 26 when he made Jaws, capturing

the imagination of a young John Singleton.

"No, not really," he says. "That comes from my own personal life."

Nonetheless, one of Singleton's favorite moments in Jaws is really nothing more than a couple of shots which preface Brody's inability to function as a protective "dad" for Amity Island's children.

The scene precedes a brief ferry ride that Brody makes with Amity's mayor (Murray Hamilton) and a few other town bigwigs. The sequence starts with a simple medium shot of Brody on the shore and a cutaway POV shot of some kids out on the water.

"Now that we've had the shark attack, we got the children swimming. There's no inherent tension, but there's tension that the audience puts on it," Singleton says. "You set something up and the pay-off is you see Brody's anxiety. You see his anxiety as he's looking at those kids in the water. And the audience is looking at those kids in the water."

The ferry ride itself occurs as a sort of coda, implicitly recalling Brody's morbid fear of water in a bit Singleton also tags as a technical and narrative feat, the characters grouping and regrouping in front of a stationary camera.

When Singleton describes the film's thematic thrust, it's as a timeless odyssey to manhood. The key moment comes, he says, when Brody looks out to sea after one final shark attack at the beach, one that nearly cost his own son his life.

"He looks at the ocean and he's afraid, he can't swim, but he has to face it. He has to face his fears. It's classic heroic art."