Republished from the DGA's Action magazine (May-June, 1969)

All photos courtesy of AMPAS.

CITIZEN KANE: Welles as Charles Foster Kane on the campaign trail.

CITIZEN KANE: Welles as Charles Foster Kane on the campaign trail.On June 24, 1940, Orson Welles began filming Citizen Kane. He had handpicked a cast, many of them members of the Mercury Theatre, and he chose a crew with equal care. Filming was completed on October 23, 1940, after 82 shooting days. Some 276,500 feet of film had been exposed. The production cost $686,000, of which Welles received $100,000.

For all of those connected with Kane, it was a memorable experience. This is how some key members of the cast and crew recalled working with Welles when asked about the experience in 1969 for the DGA's Action! magazine. The interviewees were found in many places–John Houseman at the Julliard School in New York, Richard Wilson at his beach house at Santa Monica, Ralph Hoge at his camera rental house, William Alland at an investment firm of which he is a partner, Paul Stewart at his home above the Sunset Strip, Agnes Moorehead on the Bewitched set, Joseph Cotten in the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel, Robert Wise in his Universal Office, James Stewart at Glen Glenn Sound, Mark Robson at 20th Century-Fox. Curiously, since working on Citizen Kane, Wilson, Hoge, Stewart, Wise and Robson had all become directors themselves.

JOHN HOUSEMAN - Uncredited assistant to Welles; co-founder of the Mercury Theatre

TOP HAT: Welles goes from behind the camera to his wedding

TOP HAT: Welles goes from behind the camera to his wedding

scene in Citizen Kane.

Orson and I had worked together in the Mercury Theatre, but then we came to a parting. I couldn't control him any more, and it simply wasn't fun. He had gone off to Hollywood to develop some properties for RKO, The Heart of Darkness and Smiler with a Knife. For one reason or another, they didn't pan out.

One day Orson was in New York, and he invited me to have lunch at 21. He asked me: "Would you work with Herman Mankiewicz on a script he's developing for me?" I knew how erratic Herman could be, but Orson said that Herman had broken his leg and it was a good time to get some work out of him.

Orson described the story; it was to be a multi-faceted tale about–let's face it–Hearst, or at least some legendary publisher. I was intrigued, and I agreed to come out and work two or three weeks with Herman.

Herman and I, plus a nurse to care for his broken leg, went off to Victorville and started work on the script. By the end of 12 weeks we had produced a 200-page script. It was Herman's, really; I merely edited his work.

My work was finished, and Orson took over and visualized the script. He added a great deal of material himself, and later he and Herman had a dreadful row over the screen credit. As far as I could judge, the co-billing was correct. The Citizen Kane script was the product of both of them

JOSEPH COTTEN - Jedediah Leland

JOSEPH COTTON as Jedediah Leland and Welles as Charles Foster Kane

JOSEPH COTTON as Jedediah Leland and Welles as Charles Foster Kane

I happened to be in Citizen Kane purely by chance. I had been playing in The Philadelphia Story in New York when we closed for the summer so Katherine Hepburn could make a picture. That summer I came out to Hollywood myself to do a radio show, and that's when I ran into Orson. I was with him a great deal during the preparation of Citizen Kane, and it was quite a unique introduction to films for me. Orson and Herman Mankiewicz sat beside Herman's swimming pool and discussed the script. At night I went to Orson's tiny office on the RKO lot and saw the production sketches. Orson had a visual artist sketch all the scenes, and the sketches were changed from day to day as the script changed.

We shot all night for two or three nights to finish up my part so I could rejoin the road tour of The Philadelphia Story. One night I was faced with playing a drunk scene, the one in which I wrote a bad review of Kane's wife. I thought about how to play it. The thing you don't do when faced with a drunk scene is to get drunk. But how do you avoid all the stock clichés of a drunk? Orson and I came to the conclusion that fatigue would be akin to the kind of numbness that too much drinking can bring. So we started shooting after dinner, having completed a full day's work that day. I had nothing to drink, but by three o'clock in the morning I was drunk. I felt so heavy-footed and tired that I didn't have to act drunk at all.

We were still shooting when morning came. I remember that the 8 o'clock whistle blew and the sound man cracked: "That's an interference we don't generally have on a picture."

After Orson called an end to shooting, the prop man brought on a silver tray with drinks. The big stage door was open and we saw the sunshine outside. Someone suggested, "Why don't we go outside and have our drink?"

There we were–Orson, Aggie Moorehead, Everett Sloane, Paul Stewart, myself and others–sitting around in the morning sun and having drinks. I'll never forget actors from other pictures walking down the street and seeing us. I can just imagine what they were saying: "Those actors from New York! Imagine them sitting around in the morning drinking Scotch and sodas off a silver tray!" They didn't know that we had been working for 24 hours straight.

Some people have a faculty for self-destruction, and I suppose that is developed in Orson to a high degree. He never has a conventional thought; that's what keeps him alive. He has a constant fear of conformity, and I suppose he felt if he accepted one grain of discipline, it would destroy his genius. I think it was Einstein who said that there are several hundred wavelengths and we have only discovered seven. Well, I believe there are several wavelengths for people, too. Orson's just happens to be different

WILLIAM ALLARD - Reporter Jerry Thompson; member of the Mercury Theatre

WILLIAM ALLARD as Jerry Thompson and Paul Stewart as Raymond

WILLIAM ALLARD as Jerry Thompson and Paul Stewart as Raymond

at Kane's home, Xanadu.

I remember sitting in a production meeting with Orson and a few others before the start of Citizen Kane. The time had arrived to select a cameraman, and Orson said, "If I could only get Gregg Toland–that's the man I want."

Orson had never even met Gregg, but he had admired Gregg's work [in John Ford's Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home]. Someone at the meeting spoke up: "There's no chance of getting Toland. He's under contract to Sam Goldwyn."

"I know that," said Orson. "But I'd still like to have him photograph the picture."

Just then the telephone rang, and Orson answered. A voice on the other end of the line said: "This is Gregg Toland. I understand that you're making a picture at RKO. I'd like to work with you on it."

Thus began one of the most successful artistic relationships I've ever seen. Orson and Gregg respected each other, and they got along beautifully. No matter what Orson wanted, Gregg would try to get it for him. Gregg had a tremendous responsibility because Orson was in almost every scene. But Gregg kept an eye on everything.

I played the reporter and the voice of the March of Time, but I also walked through Orson's scenes for him. I wasn't the stand-in; there was a stand-in for lighting purposes. When the scene had been lighted and Orson rehearsed his part, I studied his choreography and repeated it as Orson watched from behind the camera.

Then I had the responsibility of watching Orson during the scene and approving or rejecting the take. I didn't pass artistic judgment; I merely checked to see if Orson was getting what he wanted. After each scene, he would glance at me. If I smiled, the take was okay. If I remained poker-faced, he'd shoot it again.

There was one scene that stands out above all others in my memory; that was the one in which Orson broke up the roomful of furniture in a rage. You must realize that Orson never liked himself as an actor. He had the idea that he should have been feeling more, that he intellectualized too much and never achieved the emotion of losing himself in a part.

When he came to the furniture breaking scene, he set up four cameras, because he obviously couldn't do the scene many times. He did the scene just twice, and each time he threw himself into the action with a fervor I had never seen in him. It was absolutely electric; you felt as if you were in the presence of a man coming apart.

Orson staggered out of the set with his hands bleeding and his face flushed. He almost swooned, yet he was exultant. "I really felt it," he exclaimed. "I really felt it."

Strangely, that scene didn't have the same power when it appeared on the screen. It might have been how it was cut, or because there hadn't been close-in shots to depict his rage. The scene in the picture was only a mild reflection of what I had witnessed on that movie stage.

RICHARD WILSON - uncredited assistant to Welles; Stage Manager, Mercury Theatre

GREGG TOLAND (left) checks out Welles as he is transformed into Kane as

GREGG TOLAND (left) checks out Welles as he is transformed into Kane as

an old man by make-up artist Maurice Seiderman.

I had been the original stage manager with Mercury Theatre, and Bill Alland and I came out to Hollywood with Orson when he made the RKO deal. How we came out is a story in itself. Orson had this idea of doing Five Kings, based on the Shakespeare chronicles and to be played in two evenings. We opened in Boston at 7:30 p.m. and the play was still going at 1:30 a.m. It got rave reviews, but we ran out of money. To raise new funds, Orson decided to play the old George Arliss vehicle, The Green Goddess, in vaudeville. The idea was to lay the groundwork with a film depicting an air crash in the Himalayas, then condense the play to 15 minutes.

It was a disaster. When we appeared in Pittsburgh, the film ran backwards, and everything was a shambles. Orson shocked the theater management by suggesting to the customers that they demand their money back. There seemed to be no other course than to take one of the many film offers that Orson had received. RKO offered the best one.

The Heart of Darkness, from the Joseph Conrad novel, had been one of Orson's favorite Mercury Theatre broadcasts (as had The Magnificent Ambersons). He worked on a script, but RKO turned it down. Then he attempted Smiler with a Knife, which was about a furtive figure in the public eye. When RKO turned down Smiler, Citizen Kane was born.

Again it was a story of a public figure who had a profound effect on the population. Orson was from Chicago, and I believe he was as much influenced by [utility mogul] Samuel Insull and [publisher of The Chicago Tribune] Col. Robert McCormick as he was by the figure of Hearst.

Actually, Orson had known a previous motion picture experience. He had unearthed an old play by William Gillette called Too Much Johnson. To begin the first act, he filmed a 20-minute segment in which Edgar Barrier chased Joseph Cotten all over New York. Then there were 10-minute films that introduced the second and third acts. So he had already completed a 40-minute picture.

Orson had already shot long tests for Heart of Darkness–the tests could actually have been inserted into the finished picture. In Citizen Kane he used many of the people he had brought out for Heart of Darkness–Everett Sloane, George Coulouris, the burlesque comic Gus Schilling and others.

I left at the beginning of the summer to conduct a season of summer theater, but when I returned, Citizen Kane was still shooting. I even acted in the picture, playing one of the reporters in the press conference. One of my fellow reporters was a bit actor named Alan Ladd.

One day the entire RKO front office lead by Sid Rogell came down to the set to see what was going on. Orson suspended the shooting and we played baseball in the street until the studio brass departed. Then Orson resumed production, his creative integrity intact.

None of us knew what a furor the picture was going to raise. But then, we didn't expect anything special from the Martian broadcast.

ROBERT WISE - Editor

One of the remarkable things about Citizen Kane is the way that Orson sneaked the project onto RKO. He told the studio that he was merely shooting tests. But five or six of the sequences ended up in the picture. The projection room scene was one. Also the shot through the skylight onto Dorothy Comingore. After Orson had been shooting for a while, the RKO bosses finally became aware of what he was doing. Then they said, "Okay, go ahead."

I came on the picture when he was in the latter stages of shooting; Orson had been working with an older editor and the situation wasn't satisfactory. During the cutting, Orson became very much involved, of course. He sat in the cutting room and made cuts or asked for changes. But he didn't hang over my shoulder at all times.

I worked six months on the picture, and during some of the time I was putting in an 18-hour day. An unusual thing happened when Citizen Kane was put together. The heads of the production companies were so concerned about the reaction from Hearst that they asked to see a print of the picture. If they considered it too dangerous, they would shelve it.

So I was assigned to take the print to New York–it was my first trip there. One night in the projection room of the Radio City Music Hall, I ran the film for the company heads and their lawyers. They decided that the picture didn't have to be shelved, but certain changes had to be made to make it less indelicate. They were mostly line changes, and several of the actors had to be brought in to loop dialogue. I was on the phone almost every night to my assistant in Hollywood, Mark Robson, to confer about the cutting. Finally after six weeks of diddling, we got Citizen Kane in shape for release.

PAUL STEWART - Raymond, the butler

CITIZEN KANE: Everett Sloane as Mr. Bernstein, Welles as Charles Foster

CITIZEN KANE: Everett Sloane as Mr. Bernstein, Welles as Charles Foster

Kane and Joseph Cotten as Jedediah Leland.

The telephone rang and I heard the unmistakable voice of Orson Welles, speaking from California.

"I want you to come out and do a part for me in my picture," he said. "Have you got an agent?"

"Yes," I said. "But what's the part?"

"Never mind. Just come out."

Well, when Orson said he had a part for you, you went. So I left New York to play my first role in a picture at $500 a week, three weeks guarantee. I was on Citizen Kane 11 weeks. For the first three or four weeks, I didn't work at all.

Naturally I stood around the set, watching. And I was amazed at the way Orson worked. In those days we had an 8 o'clock call on set–Orson had to report at 5 a.m. when he was wearing the old-man make up.

The first hour on the set, nothing happened. Orson gave Gregg Toland the setup, then everyone became anecdotal. We just sat around telling stories about radio, the theater, etc. After awhile Orson began to rehearse. He had a man who walked through his scenes for him, and we rehearsed with this fellow while Orson directed. Then he stepped in and shot the scene with himself in it. Sometimes we didn't get a shot until 3 in the afternoon. Of course lighting was very difficult because of the depth of focus. Eastman Kodak had developed its fastest film for Gregg, but it was still not what we have today.

It wasn't uncommon for Orson to shoot 84, 93, 55 takes of one scene. During the Senate hearing with George Coulouris, Orson did more than a hundred takes. One day he shot a hundred takes and exposed 10,000 feet–without a single print!

I'll never forget the day Orson shot the burning of the sled. One of the stages at the Selznick studio had been made into the warehouse with a working furnace. The scene had to be just right because the audience had to see the sled go in and the word "Rosebud" consumed in flames.

When the ninth take had been shot, the doors of the stage flew open and in marched the Culver City Fire Department in full fire-fighting regalia. The furnace had grown so hot that the flue had caught fire. Orson was delighted with the commotion.

After the fire had been extinguished, one of the firemen asked me, "What's going on here?"

"Mr. Welles is making a picture here," I said.

Orson's War of the Worlds scare was still a vivid memory, and the fireman nodded and murmured, "It figures."

My first shot was a closeup in which Orson wanted a special smoke effect from my cigarette. I was rigged with tube that went under my clothes and down my finger to the cigarette, but somehow the contraption wouldn't exude smoke.

"I want long cigarettes–the Russian kind!" Orson ordered. Everyone waited while the prop man fetched some Russian cigarettes.

Just before the scene, Orson Welles warned me: "Your head is going to fill the screen at the Radio City Music Hall"–at that time Citizen Kane was booked for the Music Hall. Then he said in his gruff manner, "Turn 'em." But just before I started, he added quietly in his warm voice, "Good luck."

I blew the first take. It was 30-40 takes before I completed a shot that Orson liked–and I had only one line. That was almost 30 years ago, but even today I have people repeat it to me, including young students. The line was: "Rosebud...I'll tell you about rosebud..."

RALPH HOGE - Grip (uncredited)

CITIZEN KANE: Welles as Charles Foster Kane on the campaign trail.

CITIZEN KANE: Welles as Charles Foster Kane on the campaign trail.

I worked with Gregg Toland for 20 years, and when he went on Citizen Kane, I continued with him as head grip. So I was close to the filming and I recognized the contribution made by Gregg. Orson would rehearse a scene as he would do it for the stage. Then Gregg would explain to him why it could not be done for the screen in the same way. Gregg was careful to take Orson aside and explain these things in private. Orson was easily convinced on matters he was unfamiliar with–but not in public; you couldn't convince him of anything in front of other people.

Perry Ferguson, the art director, deserved a lot of credit for the success of Citizen Kane. It was he who devised important scenes merely by using a hunk of cornice, a fireplace in the background and a foreground chair. By using such props and Gregg's depth-of-focus lens, Orson could create the illusion of a huge set. Obviously we couldn't afford to duplicate the grandeur of San Simeon. So it was done by suggestion.

The suggestion was very effective. Some of those who saw that sequence will swear that they remember a side wall. There was none.

The same was true of the opera house scene. It was Gregg's idea to shoot from backstage, showing the lights in the theater, but not the audience. There are still people who are convinced they saw the audience in the opera house. But they never did.

The shooting of Citizen Kane was slow at the start because we had to prove certain new techniques. But then the picture moved along. There was a great feeling about Citizen Kane. It was Orson's first picture, as it was for many of those connected with it, and everyone was eager to succeed. Everyone was trying to make a good picture. But we didn't realize how good it would be.

AGNES MOOREHEAD - Kane's mother

AGNES MOOREHEAD as Mary Kane with young Kane (Buddy Swan).

AGNES MOOREHEAD as Mary Kane with young Kane (Buddy Swan).

That was a most memorable period for all of us. It was my first motion picture, as it was for Orson and nearly everyone else in the cast. He trained us for films at the same time that he was training himself. All of us were learning.

Orson believed in good acting, and he realized that rehearsals were needed to get the most from his actors. That was something new in Hollywood: nobody seemed interested in bringing in a group to rehearse before scenes were shot. But Orson knew it was necessary, and we rehearsed every sequence before it was shot. Sometimes we did a whole scene on records. No, that wasn't because we were trained in radio. Many of us had known long experience on the stage. I had done many plays, and Orson himself had appeared on Broadway with Katherine Cornell and had acted with the Abbey Players. Then, of course, the Mercury Theatre had presented some distinguished plays on Broadway, as well as having programs on radio.

It was exciting to work with Orson. There was no one quite like him to create excitement. While we were making Citizen Kane, we felt that excitement, though I must admit we didn't realize the hullabaloo that the picture was going to bring.

JAMES STEWART - Sound recordist

I was in charge of the dubbing department at RKO when Orson came on the lot to do The Heart of Darkness. His idea was for the camera to portray Joseph Conrad as the storyteller, with himself, Orson, doing the narration. He thought the camera should be hand-held, and he made extensive tests with a shoulder-mounted support–the first I had ever seen.

The Heart of Darkness didn't work out, nor did Smiler with a Knife. Then came Citizen Kane.

Orson's demands on the picture were almost impossible, but you tried to satisfy him. He was enormously stimulating to work with because he never saw anything in conventional terms. He simply wasn't interested in conventionality, and yet he wasn't different just to be different. He wanted to do things in the best, most dramatic way. He tried to draw out of you the best possible work, and he acted more as a critic than a director.

Orson discovered he could rely on me for anything. For instance, the Madison Square Garden scene: that was shot on a bare sound stage with no audience and no sound tricks, except that Orson adapted the manner of speaking in a reverberant room, waiting for the echoes to die.

He gave the track to me and said, "Make it sound like Madison Square Garden."

This was in the days before magnetic recording, and I had to reprint eight or ten dialogue tracks on film to get the right sound. Orson never liked to look at anything until it was completed, so I finished the recording and played it for him.

"You're a bigger ham than I am," he commented after hearing it. "Who's going to look at me with that sound coming at them? It's great, but give me half as much."

He was right. In my enthusiasm, I had overdone the effect, and I toned it down considerably.

Citizen Kane provided many memorable moments. I was there the night the picture was run for Louella Parsons. She walked out before it was over, and her chauffer stayed to the end.

MARK ROBSON - Associate editor (uncredited)

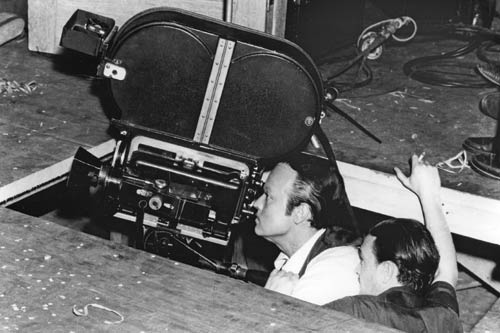

DEEP FOCUS: Director/star Orson Welles on the set of Citizen Kane

DEEP FOCUS: Director/star Orson Welles on the set of Citizen Kane

with DP Gregg Toland.

Citizen Kane was a remarkable experience for all of us connected with it, especially for the closeup view it afforded of the peculiar genius that was Orson Welles.

Orson the Magnificent! You could well call him that, because he was a magnificent director–probably the greatest that we have had in the last 30 years. He was avant garde, an innovator, an experimenter; he was theatrical, but in the great sense. He saw the world through cynical, melodramatic eyes.

He was also a magnificent failure.

The interesting thing about Orson was that he seemed to run to disaster. His ultimate failure was his success. He never prepared himself for it. He didn't really want success; he seemed to need failure. I don't think he ever really understood how good he was. He thought he was a fraud, and it amazed him when other people thought differently.

Many things happened on Kane that seemed to indicate this courting of disaster. He had a huge set of Xanadu built on Stage 9 at RKO and then he didn't know what to do with it. He feigned sickness and stayed home until he figured out how to use the set. What he finally decided was brilliant. Meanwhile the entire cast and crew remained idle.

Again, in the middle of production he left everyone sitting while he went off on a lecture tour. That seemed typical of his need for failure.

Europeans adore Welles because they think he was rejected by America. Even the young people in this country revere him because they believe he was rejected by the Establishment. I don't think it was that at all. Orson was typical of those in this country who achieve so much, so fast, so young. By 40, he had disappeared from the American scene. He was a loser–but only because he hadn't prepared himself to win.