BY ROB FELD

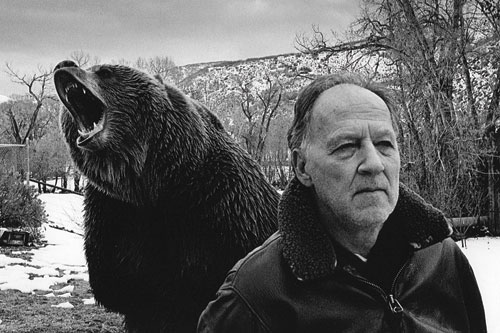

Werner Herzog inserted himself into his documentary Grizzly Man

Werner Herzog inserted himself into his documentary Grizzly Man

in search of "ecstatic truth."

Timothy Treadwell and Amie Hugenard become the subjects of

Herzog's documentary. (Credit: Lions Gate Fims)"I've never liked the idea expressed by Godard that film is truth 24 times a second. I have a slightly different version," claims documentarian Errol Morris. "Film is lies 24 times a second."

The pursuit of truth has always been a thorny issue for documentary filmmakers. What is it and how do you know when you've got it? Lately, with the arrival of digital technology, the question has become even more complex. When Albert Maysles modified his 22-pound, 16mm camera to be more maneuverable and properly synched with sound in the 1950s and 60s, he changed how documentaries were made and contributed to the rise of cinema verité. Similarly, the effects of the digital revolution have permeated every level of the documentary form and, in so doing, may have started the creation of a new one.

Today, more people can operate and afford the cameras and editing equipment required to make a film, which in turn has allowed for more intimate and personal stories to emerge; disparate films like Morgan Spurlock's Supersize Me and Bennett Miller's The Cruise, for example. Tiny cameras that don't need much light have allowed filmmakers to capture families in intimate situations and to travel almost incognito. As a result, we have seen an insurgence of personal voices with idiosyncratic points of view, not unlike the multitude of voices that have surfaced on the blogosphere. While it has been said that "now everyone can make a documentary, and most of them do," there is evidence that the intermingling of technology-spawned opportunity and newly enfranchised opinion-makers is changing the look, feel and expectations of the documentary. Though a codified school has not yet been articulated, a variety of characteristics have begun to appear.

The greatest and most obvious advance has been the incredible shrinking camera, which, with video, DV and Hi-Def, is now lightweight, hand-held and silent. It can run videotape far more cheaply than film for extended periods and takes only seconds to reload. It has led to films being made from cameras handed out to soldiers in Iraq, to audience members at a Beastie Boys concert (Awesome: I Fuckin' Shot That!), and from home movies captured by families, as with Tarnation and Capturing the Friedmans. "The digital revolution has made a big difference to us because you can make more for less," suggests Sheila Nevins, President, HBO Documentary and Family. "It's increased the volume and quality of documentary product. Things that weren't able to be broadcast because of their quality, now can be."

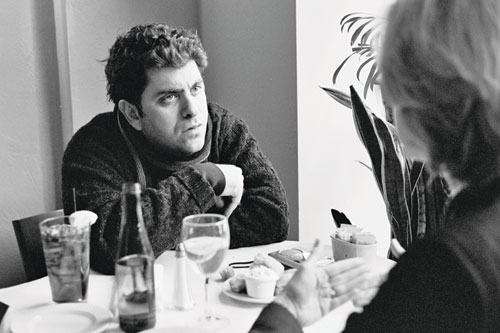

This technology has led to some compelling storytelling, heretofore impossible. When DGA and Oscar nominated Capote director Bennett Miller shot his 1998 documentary, The Cruise–an intimate and disturbing portrait of Timothy "Speed" Levitch, a homeless, pontificating, New York City tour guide cum philosopher–one of the first Mini DV cameras, the Sony VX1000, was about to come out. "I found a way of getting one before they released them," he said. "I think the serial number was like 000000000143. Everything I needed to shoot the film fit in a knapsack, that and a pocketful of subway tokens. I found this little adaptor that you screw onto the bottom of your camera that enables the use of real mics. So, Speed wore a wireless and I had a shotgun mic mounted on the camera, and I mixed it myself."

It's difficult to imagine another way of getting that unique film made. It allowed Miller an intimacy with his subject, and a portability and versatility in shooting such a verbose and mobile character, unlikely to be achieved otherwise. "I think the intimacy and maybe even the explosion of the form is directly related to the new technology," says Nevins.

Robert McNamara and Lyndon Johnson discuss foreign policy in Fog of War.

Robert McNamara and Lyndon Johnson discuss foreign policy in Fog of War.

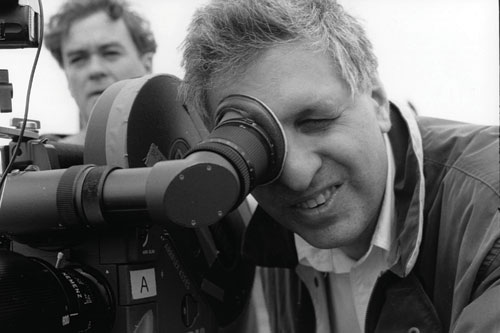

Errol Morris shoots his Oscar-winning film. (Credits: Errol Morris)

"There is no question the word processor changes your writing," says Eugene Jarecki (The Trials of Henry Kissinger). "It's the same with the cameras. It's not just a format; the medium becomes the message. My film [Why We Fight, about foreign policy and the military-industrial complex] is totally different for being made today than a film like [the anti-Vietnam War documentary] Hearts and Minds was in 1974, where the premium on the structure of a scene was greater. The vigor that was needed for Peter Davis to capture scenes in the middle of combat may be a higher form of film art than my effort to capture the verité of combat. Now you can find your story in the footage, which sounds very attractive, but there's also a capacity to become rudderless due to the plethora of possibilities offered by the fluidity of the technology."

The amount of footage one can shoot has affected those operating within the fly on the wall aesthetics of cinema verité, but also those who don't. Errol Morris, for example, who rebelled against verité by deliberately shooting films like Gates of Heaven with the largest, most intrusive cameras and accoutrements he could afford, shot Fog of War in 35mm, with the exception of his interviews, which he shot in 24-frame Hi-Def.

"I used to think of myself as the 11-minute psychiatrist because every 11 minutes I had to stop, change reels and start all over again," confesses Morris. "I have a lot more material to work with now. The problem of digitizing it and laying the transcript out has become prodigious. I think it's a terrific thing, but when you're creating non-interview images, until I see something that can do what a 35mm camera can do, I'm less impressed. But I know even within the next three to four months that's going to change. The minute you can take a digital camera and slap 35mm lenses on it, everything changes."

DGA President Michael Apted, who has worked on the landmark "Up" series for over 40 years, is working in a similar vein. "I'm trying to do multi-system documentaries, where you use one technology for one part of the film and another for another part. Film has an undeniable power to it, while tape has an undeniable use for it."

Werner Herzog, ever the philosopher, sees a bigger picture. "I am still a man of celluloid," he says. "I have used digital cameras, but very rarely and only if there was a reason for it. I don't think that matters much. What matters is that we have an onslaught of technologies in all media, that makes it possible for digital FX in films. We have virtual reality, internet, Photoshop, dinosaurs on the screen, and reality TV. That has come very fast, within the last 10 to 15 years. The point is that we have to find a different way to deal with reality and truth in general, and that's probably why people are turning increasingly toward documentaries. What technology we use in documentaries doesn't matter that much. It's a philosophical, not technical question."

In Herzog's post-modern mind, the expectation of empirical truth, represented in a traditional way, the 24-frames-a-second way, in any form or media, is misguided. For him, there is a greater chance of approaching a truth through the aesthetic experience created by the artist, than the literal interpretation of sounds and visuals.

Nevertheless, in an age where exposure to various media comprises so much of our take on reality, the technical must affect the philosophical. "No question, when you point a giant old film camera at people, there are many obstacles to getting the kind of content that we can get these days [with smaller cameras]," says Jarecki. "The smaller the cameras got, the more flexibility we found shooting in challenging conditions, whether it was on the ground in Iraq during the intensity of combat, or the sensitive environments of U.S. military installations and the American arms business," says Jarecki about the making of Why We Fight.

"The camera technologies have advanced in a way that somebody can look like a tourist yet produce an image which is theatrically exhibitable," Jarecki adds. "On the other hand, I used to pride myself on the low ratio of film I shot. Now, when you run video, you're less attentive to waste, and what that does is change your mindset as to what constitutes a movie moment. The jury may still be out on whether the kind of spontaneity and nuance that is being yielded by that more open channel of perception is actually cinematic, but I think it is."

WHY WE FIGHT: (top) The Bush defense team in session in

WHY WE FIGHT: (top) The Bush defense team in session in

the film by Eugene Jarecki (bottom) about the politics of the

military-industrial complex. (Credits: Sony Pictures Classics) Apted has had similar concerns. "I did a documentary on the Rolling Stones and had so much tape there wasn't time to look at it all," he says. "To manage it you have to do a broad stroke edit as you work, identify some rolls as garbage and throw them out, even though it's not all garbage. Although tape is cheap, post-production isn't necessarily. I'm thrilled that this new technology gives you greater intimacy and anonymity doing a documentary, and more time for the filmmaker to build contact and a relationship with a subject, but I think it can encourage sloppy thinking and sometimes no thinking at all in people who don't approach a documentary with a sense of a structure or end result."

This tendency, which is breaking down more traditional methods of working, has an inevitable effect on the form and content of the films made. "In the same way that rock 'n' rollers were forced to become song writers, directors are being forced to become camera people," says Oscar-winning filmmaker and Chair of the DGA's Documentary Committee Lynn Littman, of the way in which digital cameras have created the one-man-band filmmaker, and have increased the controversial practice of moving the filmmaker out in front of the camera. "Whereas before you could be a terrific reporter and work behind your crew, many filmmakers now find themselves in the film, which calls on an entirely different talent."

Littman notes that three of the five nominees for this year's DGA award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary (Grizzly Man, Unknown White Male and Liberace of Baghdad) featured filmmakers on-camera, while another, Off to War, exhibited a similar intimacy. "If you're going to get in that close, then you're a presence. You're in conversation and in relation to your subject in a way that didn't used to be. It's the hours and observation skills of classical cinema verité, but it's the antithesis in that the filmmaker is intruding on the scene. It's a new form."

It doesn't take Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle to know that we change the nature of any situation through the process of examining it. "Verité is not more truthful than anything else. It's just a style of photography," says Morris. How much truth one can find in a documentary has always been a gray area, no matter what form the film takes or how unobtrusive the filmmaker is. The issue is now being brought to the forefront by the increasing number of filmmakers overtly interacting with events in their films. Was Herzog too intrusive a presence in Grizzly Man, or by acknowledging his presence, was he in fact being more honest?

Herzog takes an entirely alternate position, denying that our expectations of truth are possible or even his goal. He goes so far as to request the use of quotes when referring to his "documentaries," because of their stylization and because parts are invented. "I would say cinema verité is not the answer anymore. It was the answer for the situation in the '60s. I have been working in a very specific way, which is probably not the only answer, but I have always tried to go beyond fact and reality. I've always tried to discover a deeper truth in images and situations. I call it "ecstatic truth," an ecstasy of truth. I'm one of those who literally uses no digital FX. I want the audiences back in a very fundamental position and to believe their eyes, as they did when the brothers Lumiere first showed an audience a train pulling into a station. When I did Fitzcarraldo, I pulled a real steamboat over a very real mountain, and everybody saw that this was not a digital trick."

Neither Herzog, Orson Welles, when he made F For Fake, nor Peter Jackson, when he made Forgotten Silver, have ever needed technology to play tricks on an audience. The technology, however, does offer greater opportunity to dissemble. Herzog has seen claims, which he denies, that the events of Grizzly Man were in fact digital creations. The filmmakers of March of the Penguins have also faced rumors of some digital manipulation, though they say the only manipulation was to steady the image during violent windstorms.

THE CRUISE: Bennett Miller (above on the set of Capote) shot his

THE CRUISE: Bennett Miller (above on the set of Capote) shot his

documentary about tour guide "Speed" Levitch (below)

using

one of the first Mini DV cameras.

(Credits: Lions Gate Films)

"I think what's crucial is that the documentary maker realizes that with opportunity comes new challenges to strike a balance between the values of unbiased information and entertainment," says Jarecki. "Documentary makers have to be careful about how manipulative storytelling can challenge the purity of the effort to pursue truth. It's the same balancing act journalists have always had. Sometimes the facts aren't as interesting as you wish they were." This, of course, raises the question of whether documentarians have the same responsibilities as journalists, in answer to which, one documentary filmmaker quipped, "Why place the bar so low?"

There are ways in which the current mode of placing the filmmaker in the documentary is comparable to the New Journalism of the 1970s, which gave the writer's experience of the event as much validity as a presumably objective view. "The irony of all of this is that we're living in a time and place where you believe nothing," Littman says. "In some sense people are turning to docs for information. That's a responsibility, but not necessarily for all filmmakers. If you're going into a serious area, though, where people need information, sure it's your responsibility. But the audience goes in with a job, as well. If you're interested in facts and accuracy, then your job is to do the research, or know what you're seeing."

The term documentary itself may therefore be problematic at this point. If anything is constructed or manipulated, what is one, in fact, documenting? In the realm of journalism, when we see reporters, pundits, anchors, muckrakers, tabloid journalists, essayists, and even satirists, we should have different expectations from each. However, as those lines have increasingly blurred, we have lost faith in the institution. "I'm not always sure putting a name on something is that helpful," says Maysles. "We're at a shortage for names that describe exactly what we're after. We're left with this negative thing, non-fiction."

It is possible that this crisis in confidence and suspicion of traditional news sources has aided the recent commercial success of many documentaries. Films like those of Michael Moore, or more recently, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, are looking less and less like standard news pieces–with the pretense of objectivity–and come increasingly with a specific agenda and persona attached, to which an audience can directly relate. While this form may not guarantee greater veracity, it can more easily find like-minded audiences who are willing to accept this version as the truth.

The perception of increased intimacy can be a tool for manipulating a viewer as much as anything else. New technology or old, in an era of deserved skepticism, it may behoove the viewer to choose his sources of information wisely, as much as it may behoove the filmmaker to earn and maintain the trust of his viewer. "It's a matter for the soul of the filmmaker," says Apted, who admits he hasn't always been completely even-handed on projects he's been passionate about. "Everyone's got a moral obligation and you have to exercise it, but how you regulate, codify or quantify it, I don't know."

Whatever its label, it is clear that the changes in form, content, or both, wrought by digital media, have brought non-fiction films to new audiences. As Herzog notes, conditions have been particularly welcoming for documentaries recently. Reality television was embraced by a public tired of predictable narratives in film and television, and looked for a form of storytelling and aesthetic reflection of reality that seemed more open-ended and, by extension, truthful. "If you're not getting it in one place, low and behold, there it is in another," Littman observed. "Docs are by definition personal, especially with this new equipment. It's the opposite of blockbuster Hollywood movies."

"There's something very beautiful happening," says Jarecki, "and it has to be watched closely so that it's developed aesthetically into a kind of discipline about film art, and that a school grows out of the kind of verité that evolves from new technologies."