Before making Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World in 2003, The Truman Show had been Peter Weir's biggest effects film with some 70 CGI shots; Master and Commander has over 700. It was important to Weir that all of the technology was serving the story, not the other way around. But having been trained as a three-dimensional thinker, he at first had difficulty penetrating the CGI world. Then he had a breakthrough. He laid out a blue sheet on the floor of his office for the ocean and with a fishing line towed two little square-rigger ship models around the room, blew wind on them from a fan, and filmed it with a lipstick camera. This live action footage joined with CGI animatics of the ships, done before production by Asylum Effects, and a few paintings of battle scenes formed the montage of images that Weir had in mind.

Before making Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World in 2003, The Truman Show had been Peter Weir's biggest effects film with some 70 CGI shots; Master and Commander has over 700. It was important to Weir that all of the technology was serving the story, not the other way around. But having been trained as a three-dimensional thinker, he at first had difficulty penetrating the CGI world. Then he had a breakthrough. He laid out a blue sheet on the floor of his office for the ocean and with a fishing line towed two little square-rigger ship models around the room, blew wind on them from a fan, and filmed it with a lipstick camera. This live action footage joined with CGI animatics of the ships, done before production by Asylum Effects, and a few paintings of battle scenes formed the montage of images that Weir had in mind.

This became the roadmap for creating and enhancing shots during post-production. A miniature unit, Weta Workshop, headed by Richard Taylor in New Zealand, built scale models of the British ship Surprise and the French vessel Acheron. In Marin, the ILM team, headed by visual effects supervisor Stefen Fangmeier, produced 300 shots in 12 weeks, including the 100-shot battle sequence we see here.

In this scene, the smaller and out-classed Surprise, piloted by Russell Crowe and company, is disguised as a whaling vessel, laying a trap for Acheron. After the pursuit and spirited cannon fire, and some nifty hand-to-hand action on deck, the scene climaxes with the collapse of the Acheron's mast. In addition to executing the details of the shots, the other great challenge for all units was simulating the gradual transition from dawn to full sun called for by the scene. The result is an utterly convincing mix of main and second unit action (shot at the Fox Studios Baja tank in Mexico), miniatures and ILM magic combined into a seamless piece of filmmaking art. Miraculously, no at-sea shots were used in this entire sequence.

This was shot in the tank in Baja from a Super Techno crane with a three-axis head mounted on a barge. This was a primary piece of equipment during the whole shoot because it was so wonderfully useful for creating the up-and-down movement of a vessel at sea. So we backed that up as far as we could, to probably some 600 feet from the stern of the English vessel, and on the call of 'action' we moved forward and approached at a speed that we calculated would photographically feel right. We shot at dusk for dawn and what you see is all photo-real with the exception of the rigging.

The two ships are miniatures shot separately on dry land in New Zealand, as all the miniatures were, and composited into the ocean by ILM. It was a very, very tricky shot to get right. We had problems with scale. Then there were problems with the water. We had to slow vessels down and would speed them up on another take. Then it seemed it was all taking too long. What helped was the decision to pan right to left and trek back with the camera, enabling the enemy vessel [on the left] to come in quicker. I wanted a feeling of stalking and to feel the weight of the enemy vessel and its power.

The set for the gun deck was built on a cliff near the tank [in Baja] so we could see the sea and sky out of the cabin windows. I'm one of those directors that would rather have a set be realistically designed and have the camera crew solve any problems, rather than making room for the camera. So there were no breakaway walls. Some of the grips wore football helmets because people were always banging their heads. We had all the sets on massive gimbals so there was always a sense of movement. To warm everybody up before shooting I would play a recording of an approaching cannonball and its impact.

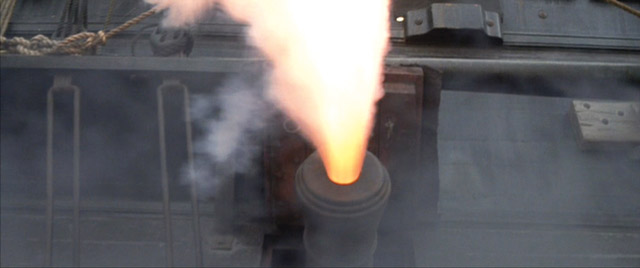

The overriding thing with shots like this one was to throw them away. You've just got to shoot it as if it was part of a contemporary action sequence rather than holding on to the beauty too long. Treat it all as if the camera had been taken back in time to what was very familiar to these sailors. We fired the cannon in the tank and in New Zealand. But it was never really entirely effective, so ILM added more flame and more smoke. I wanted it to look like stabbing tongues of fire. I wanted to make it look

deadly.

The New Zealand unit built a slightly larger miniature of the mast, about 15 to 20 feet tall, and it was shot being hit by charges and a miniature cannonball. I wanted to give a sense of the projectile, which was moving too fast to be photographed, so ILM added that as well as more flying debris. They did a five-day elements shoot and did many, many debris hits in order to have those elements to add to the sequence with the splintering of the mast. They shot debris out of an air cannon in front of a blue screen or falling into a big water tank.

This was very much inspired by paintings of naval actions, but not one in particular. Paintings were terribly important in all of these action sequences in terms of getting the volume of smoke, the attitude of ships in close combat and particularly for damage to the vessels. These are miniatures firing at each other that were further enhanced. This particular shot was given to one artist at ILM and he spent probably most of his time on it. It was an incredibly expensive shot and it required many, many elements. The sky and the water were all added. We had white smoke in the shot, which was then digitally enhanced to make it black.

This is a second unit shot taken in the tank in Mexico. It was done from the crane that James Cameron had had put in there for shooting [Titanic] and no doubt used in set construction. And it was great. Although you couldn't use the start or end of a movement, because of the jerky nature of a bucket that high, it was very smooth in its tracking use. So, we could float up amongst the rigging, which must have been 150 feet or more. The camera was always moving, even if it was panning and concealed within an actual crane movement.

That's all part of the larger miniature of the mast and rigging, and it was one of those angles they gave me that was not sketched in advance. The ropes fluttering at the right of the frame were shot at a higher frame rate just to give weight to the miniature ropes. So it was probably done at 64 frames. To get that extreme low angle it was shot against blue screen and then smoke was added to take any color out of the blue.

The next two shots were originally intended as one shot in which the mast came down, but in looking at what we had planned, I realized if it all happened too quickly it would seem just too convenient and too easy. So to have the right rhythm in the cutting, I needed to have enough material. We had no money left, so I said to ILM, 'can you add more smoke to the Acheron so that in the front part of the shot it's completely obscured and then go ahead and let it come out of the smoke?' And they were able to do it because it wasn't that expensive to add smoke to the elements we already had.

Until the ship emerges from the smoke, the audience clearly thinks that the English ship has failed in its objective. This created more tension. The slightly larger miniature mast and the miniature ships were composited by ILM. But the key thing I had to always remind them of was that it shouldn't look too smooth. You can do so much with CGI that sometimes it can look too perfect. I wanted them to imagine they were doing the shot in a camera boat that was rocking so the shot looked a little off.