By JAMES ULMER

An unassuming house in the Bronx where police

uncovered

a piracy factory.

A work station in the same house.

AA distribution operation in adjoining Manhattan apartments.

A typical lab setup.

Boxes of blank discs seized in the Bronx bust.

The product stacked and waiting to be shipped.

A vendor on Madison Avenue, later busted

with 200

illegal DVDs. (Photos courtesy of MPAA)

Less than a week after his film

Ray opened nationwide last October, director Taylor Hackford was walking down Canal Street in New York's Chinatown. As he passed a vendor, he saw a stunning sight: there on the sidewalk were dozens of gleaming copies of the new

Ray DVD, more than three months before it was due to be released. The covers of the discs even sported the movie's photos, credits and logos. It all looked amazingly real. As he examined the fake packages, Hackford realized he had stumbled upon only one of the most visible pieces of a serpentine piracy trail. Later, he would discover that trail had already slithered many times around the world, from New Jersey to Russia, China and to over 60 countries beyond, and would eventually take him to the halls of Capitol Hill. He would learn that the stolen bounty in his hand had shape-shifted from an original camcorded master to thousands of optical discs, which then spawned an estimated 1-2 million online files swapped blithely by cyber pickpockets who would probably never be seen or caught.

He suddenly thought: Is this what 15 years of impassioned work on Ray Charles' life, what thousands of man-hours by dedicated actors and crew and production staff, had boiled down to–a cheap rip-off hawked by scam artists?

"How much?" he asked the vendor.

"Fifteen dollars." Hackford knew that if he bargained, he could probably get it down to 12.

But there are no bargains to be had in Hollywood's piracy wars. The Motion Picture Association of America estimated that $3.5 billion annually is lost in movie theatre revenues and DVD sales to hard goods theft–not including Internet piracy–and the investment firm Smith Barney predicts that number has already gushed to $5.4 billion. It's easy to see why the studio distributors represented by the MPAA are hot on the trail of pirated product. As owners of their movies' copyrights, they stand to bear the brunt of those billions in lost revenue. But how does movie piracy affect the DGA and its members? Unlike their counterparts in Europe, directors in the U.S. are not the copyright holders of their work. Consequently, the creators' voice has almost always been left out of the growing piracy debate.

The DGA has begun to change that. Learning of his experience, the Guild asked National Board member Taylor Hackford to testify on behalf of the DGA before a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on piracy. The Guild's first mission was to push Congress to leverage pressure on the world's two greatest centers of DVD and videocassette piracy, Russia and China. But the DGA also wanted to shine a spotlight on the very real issues facing creative artists caught in piracy's wake.

"When pirates steal movies, they are not simply robbing movie studios of revenues," Hackford explained to the senators. "They're taking money directly from our pockets and the pension and health plans that support us and our families."

It is not only the tangible economic losses that have sent the Guild on an impassioned crusade against intellectual property theft. Movie piracy is also forcing fundamental changes in the ways directors ply their craft. For Hackford, the initial impact of piracy hit home while he was editing Ray. The director has always had a soft spot for screening his unfinished features for an audience. "I want to be there myself to see how the audiences respond, to learn from them and incorporate that into the editing process," he reports.

But when Hackford decided it was time to take an early cut of Ray out to meet an audience, the movie's producers resisted. "They were afraid the movie might get stolen," he said. "At that point it all became an entirely different experience than anything I'd known before. My creative process was being stopped because of the fear of piracy."

Beyond the process of making a movie, the vision of the director is at risk, too. The quality of camcorded copies of feature films is extremely poor compared to legitimate optical discs. And pirates can edit and otherwise manipulate digital copies of films in ways that distort a director's intentions.

But creative infringement is just one consequence of the piracy of movies and television programs on optical discs, videocassettes and Internet files. Which brings us back to those "hot" copies of Ray on Canal Street.

TRACKING SHOTS

Hackford well understood how the pirate's booty spread out on the Chinatown street could be traced. As a director, producer and editor, he was familiar with the use of visual watermarks placed onto the prints of films–both by the production during the editing phase and by each movie theatre during its exhibition–to help track counterfeit copies. Ray's distributor, Universal Pictures, reconstructed nearly every step of the illegal journey, and it wasn't long before Hackford knew just how his movie was stolen, and from where.

Like most movie theft, Ray was first taped by hidden camcorders in a movie theatre–in this case, two local theatres: the Loews Raceway 10 in Westbury, New York, and the Loews Jersey Garden Theatre in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Both camcordings were made on the first day of Ray's release, and set in motion an international twist in the film's piracy trail.

Almost immediately after it was taped, the entire movie was uploaded to the Web on the East Coast and downloaded at a mass production optical transfer house in Russia. Within days of its opening, illegal copies of Ray's 'camcord editions' were found not only on Canal Street, but all over New York, California, Florida, Georgia, Texas, and in Europe, Russia, China and dozens of other countries. All told, the Internet piracy of Ray has been identified in 68 countries, Hackford reported to the Senate subcommittee. "And that's just what we have data on."

In fact, Russia represents one of the two prime culprits for mass-produced DVD piracy worldwide. (The biggest is China, where a whopping 95% of all films sold are illegally copied and an estimated $300 million in revenues are lost annually.) The optical disc plant where Ray was copied is only one of 34 that have sprouted up in Russia, 27 of which have been linked to piracy activity and various organized crime networks, according to the MPAA. That's an exponential increase from the two facilities that existed in 1996.

The MPAA estimates that pirates bleed the U.S. film and TV industries of $275 million a year in lost income–accounting for untold losses in DGA residuals.

Compounding the problem are the massive inducements for DVD thieves. As crime goes, piracy is great business. It offers high profits at low risks, and it's a lot safer than drug dealing, a traditional activity of many organized piracy groups. Time magazine has reported, for example, that while drug dealers can make 100% profit on the sale of cocaine and about 400% on the sale of heroin, pirates can reap a whopping 800% profits on the sale of illegal DVDs. And while drug dealers risk maximum jail time and even execution in some countries, pirates frequently get a slap on the wrist–minimal fines and no jail time.

Kathy Garmezy, the DGA's Assistant Executive Director for Government and International Affairs, states the problem frankly: "You can make a great deal of money, and more often than not, without getting caught. This makes it very attractive to organized crime."

How can the industry help stem that flow of lost dollars from hard goods piracy? John Malcolm, the MPAA's Senior Vice President and Director of Worldwide Anti-piracy Operations, has achieved significant success by applying many patches to a fast-spreading problem that ultimately, and frustratingly, requires a tourniquet.

"We pick up hard copies all the time, we have forensic facilities we work with to figure out where the discs, like the copies of Ray, are manufactured," he reports. (The MPAA oversees around 26,000 raids a year of street vendors, retail outlets, labs and warehouses worldwide, resulting in the seizure of nearly 30 million illegal discs and videos in the first half of 2004 alone.) "We can trace shipping records, we develop informants. But pirates are remarkably good at evolving their practices to elude us, so we're trying to engage them at every point."

That engagement includes firing up one of Hollywood's most pro-active new weapons in its anti-piracy arsenal: shortening the distribution window between a movie's theatrical and DVD release. Reluctantly, Hackford came face-to-face with this strategy while he was editing Ray. The threat from pirates was so great that Universal decided to push up the film's DVD rollout by several months (instead of waiting the customary six months after its theatrical opening), making it one of the shortest windows of any major film.

"I questioned the strategy, and I still think we probably left $25 million on the table in theatrical revenues by putting out the DVD so soon," Hackford said. "But Universal insisted there's money to be made by the early release, and in the end, I thought it was the right decision."

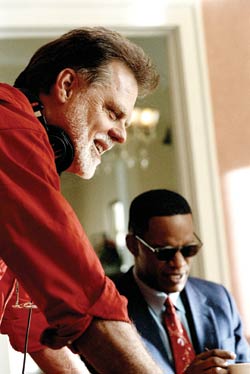

The Vision:: Director Taylor Hackford dedicated 15 years

The Vision:: Director Taylor Hackford dedicated 15 years

to getting Ray made. (Photos: Nicola Goode/Universal) The Blues: Actor Jamie Foxx in Ray. The MPAA estimated there were

The Blues: Actor Jamie Foxx in Ray. The MPAA estimated there were

42 million downloads of the film in the first eight months of its release.

WHAT COST CYBER-THEFT?

The pirates on Chinatown's streets are small pickings compared to the millions of bandits hanging out on that global superhighway of movie theft: the worldwide web. Online piracy is perhaps the most virulent form in the market today; while it accounts for only a fraction of the lost dollars that hard-goods piracy racks up, there is no question that its toll is growing. The MPAA hasn't yet calculated how much income may be lost to online theft, but the Beverly Hills-based tracking company Big Champagne has reported an ominous figure: as of March 2004, 28 million feature film files were illegally available for download on peer-to-peer (P2P) networks. The number has surely grown since then.

Following the trail of piracy surrounding Ray, Universal uncovered a mind-boggling statistic. From the time of its release until Hackford's May 25, 2005 testimony in Washington, there had been 42 million global hits to download the film through P2P networks, with 476,000 requests made in one week alone.

"My first response was, frankly, to be somewhat flattered–all those people wanting to see my film!" Hackford recalls. "But I was incredibly shocked at the same time, because [my work] is being stolen every day, and income is being lost by me, my financier [the investor Philip Anschutz], the studio and all the workers on my film."

The extent of that loss is a matter of conjecture. Hackford conservatively estimates that given the fairly lengthy data transfer times, probably only 10% of those 42 million hits for Ray resulted in actual downloads. That would represent 4.2 million potential DVD sales that were lost. If that figure were added to the total amount of DVDs expected to be sold legitimately worldwide, "that would be a phenomenal number," says Hackford. And that doesn't include the number of worldwide sales of Ray lost to street and store piracy, a figure too nebulous to estimate for an individual title.

Imagine, then, the amount of lost DGA residuals from just this one movie. In a first-of-its-kind exercise, staffers at the DGA recently did just that. Unofficially, they estimated what the loss might be in DGA residuals for a single, pirated DVD of a studio-released film like Ray. Here's the math:

Assuming an average, worldwide retail purchase price of $12 (U.S.) for one DVD (and prices can vary considerably), plus the 4.2 million in lost sales, then the total DGA income siphoned off by Ray's online piracy–not including its hard-goods piracy–would equal $90,120. That stacks up to a $60,483 loss for Hackford, a $12,013 shortfall for his crew, and $18,024 missing from the coffers of the DGA Pension Fund. And that's just the projected loss in Internet piracy for one movie.

And the problem of Internet theft will only mushroom as use of the Internet becomes faster, cheaper and more efficient. Broadband penetration is expected to reach 60% in the U.S. by 2007, according to the MPAA. The speed of transferring feature film files has already been slashed to a mere three seconds through technology like I2hub, a super-fast version of the Internet that connects more than 300 universities and institutions. Cal Tech reports that supercomputer physicists and engineers have already achieved data transfer speeds equivalent to downloading three full DVD movies per second. With bootlegged movies flying through the ether that fast, how can the DGA, the MPAA and the rest of the movie industry hope to stop cyber-thieves?

"Sure, we have online investigators checking out how many copies of a film are distributed and who are the first groups to post a movie," reports Malcolm. "But are we suing and prosecuting a very large percentage of people who are downloading and uploading films? No, because at any given moment hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people are actively trading copyrighted material of all types."

Despite the limitations on enforcement, the industry has won some important legal victories that may help dull the pirates' swords. Last spring, the industry's ongoing fight to eradicate illegally camcorded movies took a giant step forward when Congress passed and President Bush signed into law anti-camcorder legislation, making it a federal felony to record a movie projected in a theatre. It also bans a company from offering a movie or music file online before it is released for sale.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that companies that actively promote the free downloading of music or movies could be held liable for their customers' illegal acts–a clear victory for copyright protection in an online world. While the Court didn't actually settle the industry's claims against the two defendants, the filesharing companies StreamCast Networks Inc. and Grokster Ltd., the decision stated that unauthorized file sharing is illegal, thereby providing an extra weapon in the industry's anti-piracy fight.

"I think this decision will be helpful, because anything that inhibits people from doing peer-to-peer exchange for free and discourages piracy is good," says Hackford. "We have to make this a violation of the law."

Others, however, aren't so optimistic. Some contend that there are dozens of file-sharing networks that downloaders can quickly shift to at the first sign of a crackdown. And P2P operations, if threatened, can simply move overseas, where online intellectual property theft is greeted with far less strict laws and enforcement, despite the industry's efforts to promote greater international cooperation in these areas. Some also fear that the ruling's threat of big lawsuits might discourage legitimate companies from designing new products intended for lawful use, because these products would almost certainly expose the companies to litigation if they ever got into the hands of pirates.

A NEW GENERATION GAP

Another problem faced by MPAA and law enforcement authorities is the potential for bad publicity. The vast majority of online thieves are hardly callous criminals operating out of grungy, padlocked urban coves; they're teenagers and college kids and older professionals, "operating" out of ordinary homes and offices around the world. Who wants to be the one to prosecute John Q. Student for downloading a Britney Spears song or a Disney movie?

Certainly prosecutors and the MPAA would prefer to focus on groups who abuse copyright law, rather than going after individuals. The MPAA, for example, has filed lawsuits in four continents against 100 owners of bitTorrent Trackers, eDonkey servers and Direct Connect hubs–P2P index and file-sharing servers that Malcolm says "profit on the back of theft" by catering to pirated material. Still, individuals are not completely beyond the industry's sights, if only as highly-publicized deterrents for the wider population. Two studios and a number of record companies recently filed suit against dozens of California students for illegally using super-fast I2hub filesharing technology. The students, sued as "John Does," are subject to fines up to $150,000 per movie or song copied.

Faced with a disease like piracy that spreads so quickly, eludes detection and often outwits the means to fight it, this may be one of the more effective–though controversial–defense strategies for Hollywood: to demonstrate the consequences of illegal downloading.

"It's an issue of changing a mindset," says the DGA's Garmezy. "Most people don't have any sense of the implications or who they're really stealing from. If you don't have a sense of who you might be hurting, it's hard to make this problem real."

But for younger online pirates, the problem isn't just educational, or even a case of prevention. It's generational. As Hackford puts it: "These kids are the babies of the Internet generation. They're literally born into an understanding that this is all free exchange, that open access is practically a birthright. Changing that is going to be tough."

So what options are left for fighting piracy in the future? "I, for one, am skeptical that a be-all and end-all solution exists," says Malcolm. "Even as we take greater enforcement actions, pirates can always find new technologies to use." Still, Hackford believes a number of new and cutting-edge technologies in detection and encryption might be the best answer to fighting movie theft. "I think better technology is the only thing that's going to work for us," he says. "It's got to be the main way we control the illegal dissemination."

Hollywood is currently debating another way to control it, too: reducing the already shrinking window between theatrical and DVD release down to nothing. Like many, Hackford maintains that the day when a film's DVD debut arrives day-and-date with its theatrical bow is virtually inevitable. (ABC/Disney recently announced it would endorse this option, a move that predictably drew howls of protest from the National Association of Theatre Owners.) Already, Mark Cuban's HDNet Films is planning a slate of movies scheduled to be released on its cable network, in theatres and on DVD, all on the same day. Director Steven Soderbergh has signed on to deliver eight films for the company.

"Clearly this is coming sooner than most would anticipate," Hackford says. "As a director, I love to make films for a big screen, for a common experience within a cinema. But in the future, many more people will see my films on a small screen at home than on a large one. And there's something sad about that. Tragic, actually."

Still, the DGA remains undeterred in its anti-piracy efforts. Given the challenge of facing an enemy that so powerfully tests the limits of technology, ethics, enforcement, education and even geography, it is the commitment of the Guild and the example of directors like Hackford that may be one of Hollywood's best hopes for tracking, and trouncing, the pirates of tomorrow.

"We as the DGA must offer tremendous help with this issue," Hackford insists. "We have to communicate to Washington, and to our own members, that this battle has a huge impact on our work, our health and our pensions. If we lose, these can all be decimated. Nothing less than our lifeblood is at stake."