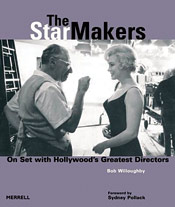

(Merrell, 351 pages, $49.95)

By Bob Willoughby

Foreword by Sydney Pollack

A good movie-set photographer must be a great tightrope walker, somehow managing never to be a distraction to actors or directors, yet to be everywhere present, ever at the ready. Beginning in the early 1950s, Bob Willoughby became one of the most successful photojournalists in the film industry and the first "outside" photographer to work on Hollywood's closed sets. His images of such cinema icons as Marilyn Monroe and John Wayne are so ingrained in our cultural consciousness they practically defined those stars. And while actors and actresses garnered Willoughby the magazine covers, they were not the only apples of his eye.

His own considerable interest in filmmaking kept him training his lenses on directors. Star Makers has gathered more than 30 years of Willoughby's observations under one roof with 500-plus illustrations. It is a unique record of more than 50 directors in action — with filmographies for each — accompanied by Willoughby's descriptions, explanations, opinions, insights.

In a long spread on Mike Nichols' plunge into his first film, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1965), Willoughby reports that Nichols "borrowed veteran film specialist Doane Harrison from Billy Wilder for advice on cutting and shooting..." He also tells of some members of the crew leaving the job after the first week because the script's "dialogue was so acid, so bitter."

"Veteran film director George Cukor was a character," Willoughby writes in his coverage of My Fair Lady (1963). "It was terrific to photograph him emoting as he acted out parts for the actors." When "Cukor became anxious about the actors being distracted, [he] built [a] series of baffles around the area being filmed." Willoughby's wide shot of the baffled set documents a valuable piece of film history. Someone on the crew told him that "he had heard of these baffles being put around the set only once before: when Cukor was directing Garbo at MGM."

Alfred Hitchcock's penchant for unique production devices are evident in Marnie (1964), as Willoughby shows us special ceiling tracks for a camera descending under fold-back balustrades. Another shot is of actress Tippi Hedren being bizarrely lowered to a bed by a heavy strap held by men on either side of the camera. Hitchcock was gracious and helpful to Willoughby. David Lean on Ryan's Daughter (1969) was not. During Rosemary's Baby (1967), Roman Polanski told Bob that he never made a master shot so that it would be harder for "the studio to recut his films." On The Children's Hour (1961), William Wyler (of the million and two takes) was very interested in what Willoughby chose to shoot.

Sydney Pollack "was the most cooperative director" of all. During They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969), Willoughby writes, "He would hold the roll until my radio-controlled cameras [mounted on the movie camera] were in place and ready to track his action." And in his Introduction, Pollack writes that Willoughby understood the Horses material so well, he helped the director tell the story of his own film.

Review written by Lisa Mitchell