Director Clint Eastwood (right) with camera operator Stephen S. Campanelli

"We were shooting the first sequence of Play Misty for Me in the Sardine Factory at Monterey," Eastwood wrote. "[Director] Don Siegel was behind the bar in his role as a bartender in the opening scenes. I noticed that he looked a little uptight and he admitted he was nervous because he had never acted before. 'That's funny,' I told him. 'I don't feel at all nervous and I've never directed before.'"

That may have been because he had spent years diligently studying the work methods of the directors he had served as an actor. When the time came for Misty he was ready. Since then he's proven to be a passionate filmmaker with a focused, methodical, yet unstressed work ethic.

Many members of an Eastwood film crew have been with him for years, some for decades. UPM Tim Moore had heard from AD Robert Lorenz and 2nd AD Melissa Lorenz, with whom he'd worked on other projects, about what it's like on an Eastwood set. He saw it firsthand on Mystic River, which opens in October, where he learned it was even better than he'd expected.

"What an experience," Moore said. "[Clint] knows exactly what he wants. When he says he's going to do it a certain way, you can put that line item in the budget and he's going to be true to it. If anything, for me it's making sure you're prepared in advance. We pulled a lot of things forward. We had 43 shooting days scheduled that Clint shot in 39 days. Out of those 39 days, I believe on seven or eight of them we wrapped at lunch. The toughest thing for me was when [1st AD] Rob would call from the set and say, 'Listen, we're ahead, we're bringing this forward.' So it was making sure the production team all knew, not only actors, but locations and everybody else, that we would be shooting scenes that were on the next day's schedule."

2nd 2nd AD Katie Carroll added, "As a trainee, we'd heard the rumor about how quickly he works, so when I got Blood Work I was thrilled. On any other movie when we say, 'Oh, we're going to try and get that scene today,' it never happens. In this case I had to convince everybody that 'Yes, we really will get that scene today so please be prepared, and here are your lines and please know them.'"

Mystic River's 39-day shoot is not unique for Eastwood. On Play Misty for Me, which was budgeted at $950,000, Eastwood came in four days early and $50,000 under budget. Over the years, along with earning honors such as the DGA Award and Oscar for helming Unforgiven, he's earned a reputation as a director who'll deliver on or under budget and time. Yet, it's a reputation he really doesn't care for.

"Everybody keeps saying, 'Well, he only does one take.' " Eastwood said. "Even if that were true, I don't like the reputation. I don't think anybody likes that efficiency label. What I like is to be efficient with the storytelling. To me, it's whatever it takes to do the job. I'm not out to save a buck. We've budgeted a film and it will live within the budget, that's for sure.

"The big question, for me, is how to do it so that it's efficient for everybody, so the actors can perform at their very best and with the spontaneity that you'd like to find so that the audience will feel like those lines have been said for the very first time, ever," he added. "Then you've got a believable scene, then a believable group of scenes and finally a believable picture, because everybody is thinking it seems real. It seems like they're saying it right away, instead of saying it for the 50th time. Everybody's heard those nightmare stories of somebody doing a take 20, 30, 40 times. Other than obvious errors like forgetting a line, often I can't see any difference between take one and take 20."

Eastwood (left) with actors Tim Robbins, Sean Penn and the child actors portraying them on the set of Mystic River

One element of an Eastwood set is the absence of anybody yelling "quiet on the set." There's no need because it's always quiet. "You can just hear a pin drop on the set," said

Mystic River 2nd AD Melissa Lorenz. "It's great. Everybody wears a radio, and everybody wears a headset that has a radio, including the teamsters, so there's never an open radio. There's never that loud squawking."

Eastwood explained that years ago he noticed how the Secret Service Agents at the White House communicated. "They had earphones in the ears," he said. "You didn't hear them talking, but they were all talking with one another all the time. I thought, 'How come these guys can do this, but on a movie set you hear all these guys screaming and yelling all the time?' So I decided I wanted set communication just like the Secret Service. Everybody should be able to communicate without having all this yelling and screaming.

That's the way I've been working ever since. I have all the departments on headsets so they can say, real softly, 'We're shooting.' It's quiet. You don't have to have that 'ACTION! QUIET EVERYONE!'"

Penn and actors Laura Linney and Kevin Bacon on set

An added benefit of this was quickly seen while location shooting. "The neighborhoods that we shoot in, you get a lot of very nice people, people who are glad to have you there," he explained. "But then you always have those idiots who say, 'Oh, they want quiet, I'll give them quiet,' and they empty the garbage can on the driveway or something. So, when I'm out in the neighborhood, just like on the set, I like it quiet. That's also out of respect for the neighborhood. I don't want to keep everybody awake, or disturb their life any more than we have to by being there with a bunch of trucks and stuff. You shoot very quietly, efficiently, and move right on down the line. That way, the neighborhood is more appreciative. They've enjoyed our visit as an experience. It hasn't been the movie cliché of some guy in leggings and a megaphone. It works really well, and that consideration permeates through the whole crew."

The quiet also helps in other ways. Sometimes the cast and crew may not even realize they're on camera. "When you work with kids, especially, you want to be ready to turn the camera on at a moment's notice. You end slate and that kind of stuff," he said. "You want to be able to catch all their stuff. Sometimes I'll have a Steadicam sitting there, ready to go.

"On True Crime one little girl had hurt herself and she was crying. She also had this scene in the film where she was crying. So I said to an actress, 'Would you just go comfort her. Say anything you want.' And I photographed it.

"In fact, I do end slates a lot, even with professional actors, because it just doesn't disturb everything," he added. "When you're set to go with something, you say, roll it, and everybody just kind of flows into it as opposed to somebody coming out and going 'whap' with a slate. It's just a distraction you don't need."

Mystic River's 1st AD, and one of the film's producers, Robert Lorenz, first worked with Eastwood as a 2nd AD on Bridges of Madison County; he also met a young PA who would become his wife and frequent 2nd AD, Melissa Lorenz, on that picture. He moved up to 1st AD on Absolute Power and said, "The sets are often so quiet that, for the uninitiated, it's hard for them to know whether we're rolling or not. A lot of people ask, 'Did we roll on that rehearsal? Or are we rolling right now?' That's kind of the idea behind his work method. Everything needs to be focused on what's in front of the camera. Everybody's attention needs to be focused there. It's just expected if you're going to be anywhere near the set you're going to be paying attention to what's going on."

Over the years Lorenz said he's learned, through very subtle signals from Eastwood, sometimes a flick of the finger or a look, to get the cameras going so they don't miss a real moment with main actors or background extras.

Sean Penn in a scene from Mystic River

The credits on Mystic River also feature other longtime Eastwood collaborators. Composer Lennie Niehaus, nominated for a BAFTA Award for his score of Bird (1988), began with Eastwood on Pale Rider (1982). Casting director Phyllis Huffman first worked with him on Honkytonk Man (1982). Costume designer Deborah Hooper started in the wardrobe department on Pale Rider while stunt coordinator Buddy Van Horn first worked with Eastwood on Don Siegel's Coogan's Bluff (1968) and later directed Eastwood in Any Which Way You Can (1980), The Dead Pool (1988) and Pink Cadillac (1989). "And we have other rules to keep the set calm and focused," Lorenz added. "We don't pass out paperwork on the set. It's not the place to be reading schedules, messages and so forth. It's the place to focus on what's being done. First time for a lot of grips, electricians and day players, it's really disconcerting because they don't hear 'rolling,' they don't hear 'cut.' Then soon they realize what they need to do is pay attention to what's going on in front of the camera all the time."

Based on the best-selling novel by Dennis Lehane, Mystic River is a complex psychological thriller centering on the reverberations of a child molestation case that occurred some 20 years earlier to one of three close friends (played by actors Sean Penn, Tim Robbins and Kevin Bacon). Eastwood was already familiar with Lehane, having been recommended to his books by a close friend, and when he read a book review of Mystic River, he became intrigued by the reverberations aspect.

"Mystic River just smelled interesting to me," Eastwood said. "So I read it and liked it right away. Even the dialogue in it was great. I had been working on Blood Work with [screenwriter] Brian Helgeland. I said, 'Brian, there's this book I've got that's really interesting and I'd like to make it. It reads almost like a movie. [Lehane] has a terrific way with the characters.' So Brian read it, agreed, we talked about it and he wrote a screenplay, in two weeks in fact. It was a good screenplay right off the bat. He accomplished a lot of what I wanted to get on film.

"Then we went back and played with it. Putting certain things back from the book that Brian left out, and we just balanced it around and then all of a sudden it was there. And before I was finished Blood Work, I had this project. So I just said, 'I'm going to go right into Mystic River because I like it.'"

In short order, Eastwood called on his longtime collaborators, including legendary production designer Henry Bumstead, to get started. Bumstead, winner of the Academy Award for his sets on To Kill a Mockingbird and The Sting, had first worked for Eastwood on High Plains Drifter. But Bumstead was under contract to Universal, and when Eastwood began making films for Warner Bros., the two wouldn't work together again until Unforgiven. Now, 88, Bumstead said he'd have retired long ago if it weren't for Eastwood.

"So, when I'm out in the neighborhood, just like on the set, I like it quiet ... out of respect for the neighborhood."

"I just enjoy working with Clint so much," Bumstead said. "I think Clint is a wonderful director. He does his homework and he knows exactly where he wants to put the camera. There's no big discussion every morning where everybody has an idea where the camera should go and how the scene should play. He appreciates good sets that are worked out and have some thought behind them. He always said to me that my sets are very easy to shoot. So with Unforgiven I decided I wouldn't retire, I'd just work for Clint. That's really what's happened. I've done everything Clint has done since then with the exception of Bridges of Madison County."

Bumstead flew to Boston, and with location manager Kokayi Ampah, whom Eastwood met while filming Wolfgang Peterson's In the Line of Fire, began narrowing down locations. Ampah found an abandoned pharmaceutical warehouse in Canton, Massachusetts, about a half-hour from Boston where interior sets could be built. Eastwood also consulted with Lehane, asking the author "what's in you're imagination and what's really there?"

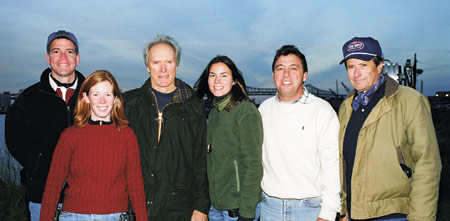

DGA members on Mystic River: (L-R) 1st AD Rob Lorenz, 2nd 2nd AD Katie Carroll, director Clint Eastwood, 2nd AD Melissa Cummins-Lorenz, UPM Tim Moore and stunt coordinator Buddy Van Horn on location in Boston.

Cinematographer Tom Stern was a gaffer on Eastwood's Honkytonk Man, Pale Rider and Heartbreak Ridge, moving up to lighting consultant on Bird, then chief lighting technician on a number of other Eastwood films and finally becoming a cinematographer on Blood Work.

"I was quoted in The New York Times as saying, 'Clint's the most articulate nonverbal guy I've ever met.' " Stern said. "I like to use musical metaphors, and it's like if you're in a jazz quintet or something where you sense what the leader is doing. Really, the effort is to be in synch with him. One tends to have real spare conversations, a note of this or an idea of that.

"And he's on top of everything. The thing that's bizarre or unusual about him is he knows all the lab functions," Stern said. "He knows all the nuts and bolts that are going on. He never micro-manages anything, but if something starts to drift away from the direction he feels he wants to go, he calls attention to it."

Eastwood only uses storyboards when special effects are involved, such as on Firefox and Space Cowboys and doesn't prepare shot lists either. Instead, the film is in his head.

Penn and Robbins contemplating another tragic turn in the lives of the characters of Mystic River

"You visit the set. You get ideas. You say, 'You know, I could bring the person in there and I could come around there.' You kind of rough it out in your mind," Eastwood explained. "When you come back, a month or so later, to actually be on the set, you might notice the art director's got some nice things that you didn't know he was going to have. If you don't like them, you can move them around. But if you like them, you think it'd be nicer if the actor came in another way. It evolves. It's like clay. If you're locked into something, if it has to be an exact duplicate of the mold that you had in your brain and you can't deviate from it, then you're going to be locked in. Sometimes people aren't comfortable. Or an actor comes up with a splendid idea, which sometimes they do. They say how about if I do this? And I say let's do this one, and after I make sure we have it say, 'OK, that sounds good. Try it.' I'm very sympathetic to actors trying things because that's the way I like to be directed myself.

"You've got a bunch of creative minds on the picture — the art department, wardrobe department — everybody has good ideas. You take those good ideas and it all goes into the pot and it becomes the final. Don Siegel always used to make fun of himself and say, 'God, I don't care who comes up with a suggestion, if it's a good one I'll take credit for it. If it's a lousy one, they can have it back.' He used to joke about it. In essence what he was saying is that there are an awful lot of people who could have input and you might as well not stifle them. Try to encourage them. I know there are some directors I've worked with who say, 'Don't change.' I say, 'OK.' If they want to do that and it works for them, that's fine."

"You've got a bunch of creative minds on the picture — the art department, wardrobe department — everybody has good ideas... there are an awful lot of people who could have input and you might as well not stifle them. Try to encourage them."

He also prefers camera work that doesn't draw attention to itself. He does carefully construct visual sequences so they flow, but in a rhythm that enhances the storytelling. "I don't like noticeable camera moves all the time, where right away you take the audience's eye and put it on something and you think, 'Oh, there's three guys standing there: a dolly grip, an operator and a focus guy.' You can just see them because of the moves. Mystic River has a story you don't want to detract from. I've always said the one advantage an actor has of converting to a director is that he's been in front of the camera. He doesn't have to get in front of the camera again, subliminally or otherwise."

Stern pointed to a moment on Mystic River as the perfect example of how Eastwood can concisely convey how he sees the film. "We'd all read the book, the script and talked with Clint about it. Henry Bumstead, Rob and I started looking at places and started putting together a suggested film. We showed him the direction we were going, but then it was like a lightning strike out of the clear blue skies. Clint had an entire kind of idea of disturbing the horizontal, if you will. Normally, a lot of times things happen on the same level. He pointed to the scene where a girl is found dead at the crime scene and she's found in a pit. Immediately we're looking down at her and looking up at Kevin Bacon. That was an idea that we developed throughout the film."

Editor Joel Cox has worked with Eastwood since 1975. Cox was an assistant editor on The Outlaw Josey Wales. He is currently editing Eastwood's documentary Piano Blues for the PBS series The Blues. Cox explained that when they edit a feature film together, a process they both refer to as the "final cut of the script," Eastwood is just as efficient as he is on the set.

"I generally don't go on location with him because he likes me to see the film first, and then we talk each night about what I've seen," Cox explained. "Clint might shoot 35 or 37 setups a day. And, he'll shoot two or three scenes. If the scene is complete, I edit it and I work right behind him. I basically just follow whatever he's shot, from scene to scene, send him what I've done and we talk about it. Then when he's done shooting and when I'm done, which is about a few weeks after he's done, we go up north, to Carmel, sit down and go over it. For Mystic River we were gone for nine days and then we were done. Blood Work was eight days, Space Cowboys was a little bit longer because we had a lot of blue screen shots.

"He's a great believer in seeing your film on a screen because it will look different than on a computer screen and you cannot tell focus from tape. After we convert the film, we'll look at it again and go back and make more changes. The computer gives us a list of the changes, we go to the reels and make them and in a few days we can look at it again. It's generally about two or three runs like this and we're finished."

Cox also gave an example of how Eastwood structures his films, shots and edits from the get-go. "On Bridges of Madison County, the key he gave me was, 'until the main characters (played by Eastwood and Meryl Streep) sit down at that kitchen table in the kitchen we're going to play this loose,' " Cox said. "It's like when you meet somebody, and this is how we referenced it. 'If I met you today, we wouldn't meet up against each other, like in close-ups. We'd meet each other wide, shake hands, "How you doing?" As we sat down and talked, we'd start to form a relationship. So that's how you would work them in.' On that film, in particular, he also gave me every one of the songs he planned to use before he shot the film. He said, 'This song goes in this scene, this song goes in that scene.' He comes in very prepared as a director."

Clint has another expression that he whips on me a lot because I have too many advance degrees and it's gotten down to a kind of look he gives me over his nose when I start being analytical," Stern laughed. "It's 'The Paralysis of Analysis.' He doesn't want to do that. He's spontaneous or improvisational. It's his spirit. He's very, very intuitive."

Rob Lorenz added, "Analysis Paralysis means you go from the gut. That's one of the reasons he likes the first take so much, it's got that spontaneity. Oftentimes if it's a scene in a restaurant where the actors are seated anyway, the shots he uses are the times he rolls in between takes, when the extras are sitting there talking amongst themselves. He's just moving the camera around, picking off shots with these guys here and there."

As the patriarch of a talented group of collaborators, he's brought many along with him, providing opportunity and advancement with a list of films that are remarkably varied in subject matter. Clearly, Eastwood has surrounded himself with an efficient team who know what he wants and who are eager to work with him again whenever he finds a story that "smells interesting."

Mystic River is the fourth time he's directed without having to also appear in front of the camera. So which does he prefer, acting or directing? "I've always preferred directing," Eastwood said. "I must say I've had my enjoyment playing characters, seeing what you can bring to life, what works and what doesn't, but I think directing I've always liked more."

I looked at Raoul Walsh's White Heat recently, and that scene where James Cagney goes crazy in the mess hall. When I watched that scene, I thought, "You could shoot a hundred different trick shots in there, and point of views and different things." But Walsh just stays with Cagney, just kind of lets him do his thing. There's very few shots. Yet the actor is so effective. And you're not detracting from him by cutting away to a lot of stuff. Raoul Walsh was kind of a ready-to-go shooter. And if you look at Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard, the only real close-up you remember is at the end with Norma Desmond saying, "I"m ready for my close-up, Mr. DeMille." She comes right into it. If you'd shot the entire film in close-ups, that ending shot wouldn't have been effective at all.

With those directors you got the feeling of geography all the time. You got the feeling of where they were, of the scene and you felt the whole room, not cutting back and forth between two heads. I like that. Maybe working with Don Siegel, and other people, by just watching them and watching movies from that era, you notice they weren't so in love with head shots. I've always felt that the easiest two shots to make in a movie are a wide vista or a big huge head shot. But all that connective tissue in between is where you really put the scene together. Not that head shots aren't important. They are important items, but when you use only them, everything becomes very back and forth, instead of letting things play out.