The DGA community came out in full force on February 19 to celebrate the art of commercial directing at the 5th Annual "Meet the Commercial Nominees" reception and screening. There were more than 150 supporters who came to the Guild not only to congratulate the nominees, but also to acknowledge the growing influence of commercial directing on the film industry as a whole.

The DGA Fifth Vice President Michael Apted opened the evening by appreciating the extensive impact commercials have had on feature film. "What you do has influenced what movies do," Apted said. "You've revolutionized some of the language and grammar of film the look, the style, the cutting, the photography, the storytelling. You showed us how to be light on our feet, cover ground quickly and remove the fat ... You made the dialogue between filmmaker and audience a lot more fun for us all.

"I know enough about your work to understand the great skill it takes to tell your stories," Apted continued. "Stories that despite (or because of) their brevity, can enter the culture and become as much a part of people's lives as hit movies or great pop songs."

Nominees Craig Gillespie, Noam Murro and Baker Smith spoke to the crowd assembled in the Guild Theatre and with DGA Magazine during the event. Nominees Dante Ariola and Leslie Dektor were unable to attend.

Baker Smith

Baker Smith, who went on to win the DGA Award, claims he had wanted to direct "since I was in the embryonic stage of my life. Ironically, I have no formal training in directing."

Smith admits he's drawn to humorous spots but insists, "I'm attracted to good concepts and story first and foremost. Having said that, I like to laugh and I don't take myself too seriously." However, he does take his job seriously and readily defends it to any doubters, especially those who question storytelling ability in a limited-time frame.

"The biggest misconception about commercial directors is that we are unable to carry a story; I beg to differ. If you look at all the nominees' work, you will find a strong narrative thread. That didn't happen by accident. These days a commercial director must captivate the audience to pay attention, then motivate them to buy, all in 30 seconds."

Smith suggests commercial directors are adept at meeting tough deadlines. "We're able to turn our spots around so quickly. We get the boards, we read them, we bid them. The pre-production is accelerated, the production is accelerated and the editorial is accelerated to get them on air. We seemingly get it done. It's 'well, you did it last time in a week, why can't you do it in five days this time?' And just being overachievers we go 'OK!' We are our own worst enemies in that way."

Among commercials earning Smith the nomination were some with period themes and casts of thousands, supplied through digital post-production. "We're able to multiply a lot of those shots. To be able to make 400 look like 1,500 is relatively quick, cheap and easy the technology is insane! We seem to have a post-production supervisor show up and say, 'shoot it the way you want, we'll fix it,' which I think is liberating for us on this side of the camera, I love that. Before, it was, 'shoot them against the blue screen, it has to be locked off.' "

That's the upside but under the present business climate, "it's definitely, 'get it done faster, cheaper, quicker' and that is just the world we live in. You choose to live in it or go somewhere else. Sometimes they've got the money and it's two weeks (to shoot) but those (productions) are few and far between."

To date he's been exclusively involved in commercials, but Smith, through his company, harvest films (with executive producer Bonnie Goldfarb), is currently in pre-production on his first documentary. "I'm not directing it. I'm serving as a producer. I'm actually very excited by working behind the scenes and helping the director's vision become reality," Smith says.

"I'm fortunate that the agencies I've been working with in the past couple of years have relaxed to the point where they say, 'This is our idea but if you have something better, please bring it to us.' Or, 'how do you see this?' And they listen. They may not do it that way in the end but they listen, your voice is heard, that's what's fun.

"When I started, 14 years ago, the director would get the concept, shoot it and it would just sort of go away," Smith adds. "Agencies edited it and you see your work on the air. In the last couple of years, I'm seeing, 'Who's the editor you like to work with? Will you do a director's cut in the time that we have?' That's great for directors. There's more ownership and more pride."

Craig Gillespie

Craig Gillespie suggests that commercial directors "tell a pretty complicated story in 30 seconds. It's a lot harder than it looks to do a 30-second commercial."

Gillespie became a director out of sheer perseverance. "I hoped to get a break from the agency where I worked but it didn't happen so I shot one myself a big gamble! I spent $20,000 of my own money and built my own sets for a couple of pizza spots.

I got signed up pretty quickly after that."

Since then he's made a name for himself by honing in on the comedic. "My heart's in comedy. I have a broad definition of comedy.

I only want to do comedic material but within that there's such variety and degrees of subtlety."

While everyone likes to work with a core team, reality dictates that's impossible, especially in the "faster, cheaper, quicker" world, but that, according to Gillespie and echoed by others, "is now part of the challenge." Within that framework, directors seem to agree that agencies allow certain freedoms. "I have my own voice and style and they give me freedom," says Gillespie, who also admits his work "got simple. It used to be more technical but that doesn't resonate with audiences as well now. I trim the fat and get to the crux of the idea."

Gillespie is "going down the features road." Admitting there are crossover concerns, Gillespie acknowledges commercials and features are, in certain ways, such different beasts, "but whatever you do, you have to keep the viewer engrossed. No matter what you're doing, you have to know how to relate to actor and audience. Find your own voice and be true. Be aware of what's around you." Despite the need to be prepared before shooting, Gillespie allows that, "if an actor comes up with something that works, I'll use it," after all, "you don't have a home run if it doesn't have soul."

While the same can be said of any medium involving actors, Gillespie suggests that the "use of dialogue is extremely important in commercials. The dialogue has to be specific and down to the beat, even a look can work so much more than in any other medium because of the time constraints." Nominations and awards certainly create a greater awareness but Gillespie insists there's no room for complacency. "The nature of this business is short-term memory. It's fickle and I have to focus on the next three months always."

Noam Murro

Noam Murro can't remember a time when he didn't want to be a director. "Directing was always in front of me and there are as many ways of achieving that as there are people."

While his work is not influenced by what others do, he was influenced to become a director after seeing Bernardo Bertolucci's The Conformist. "It changed my life," he says.

Murro spent some time as an art director and then as an associate creative director, before moving into the director's chair so "this nomination is a great honor. It's playing with the big boys if you will. There's only a few places to be recognized, not just for your work but the frame it's in the DGA, where you're judged by your peers." But Murro is realistic. "You have to appreciate the accolades and awards and move on, it's not the goal. You have to do good work."

Murro sees similarities between the world of commercials and the studio system in two major areas achievement and creative. "Only studios are the client and producers are the agency." However, Murro suggests there's no "opening weekend" mentality from the agency. They "view success on creative merits, not on business performance." But there is pressure. "Creativity and money is where the tension is and always will be," Murro says and the end result is "95 percent schlock, while five percent is great. It's the same everywhere, without a good concept there's nothing if it's not great, the spot isn't going to be great!"

To Murro, also about to dip his toe into the feature pool, there's no real difference between directing films and commercials. "A great poet can effectively write a great novel. You need to be a great storyteller. It's the difference between a mini and a minivan. They're both vehicles. It's down to whether you look somewhere else when you're driving and have an accident."

He obviously has a great creative input but Murro insists that the whole process is collaborative, refusing to take any credit. "There's a tremendous amount of competition and it keeps you honest. This is a very complex job with only a certain time to prep and tell a story. The challenge for any commercial director is to make them precise!"

Murro's style and client list is varied, but that hasn't been through his "chasing" those different clients or products. "If you chase something, it's wrong," offers Murro. "You have to be a good consumer of art. I consume as much as I can and filter it through my system." However, with 10 percent of his work for Europe, Murro is faced with the prospect of commercials for different products and he's adamant about one. "I won't do cigarette advertising."

Murro now works under his own banner, Biscuit Filmworks, and reveals, "I like freedom and no responsibility, but now I have freedom and responsibility it's bitter and sweet."

Meet the Nominees: Commercials

55th Annual DGA Awards

Pictures

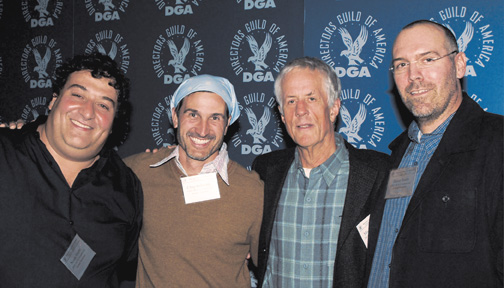

Commercial Nominees Noam Murro, Craig Gillespie, moderator Michael Apted and Nominee Baker Smith at the DGA Commercial Nominees symposium. (Photo by Joe Coomber)

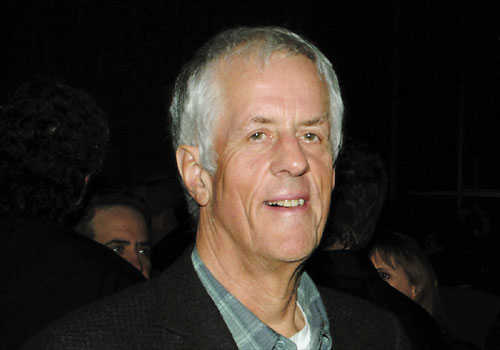

DGA Fifth Vice President Michael Apted at the DGA Commercial Nominees symposium. (Photo by Joe Coomber)

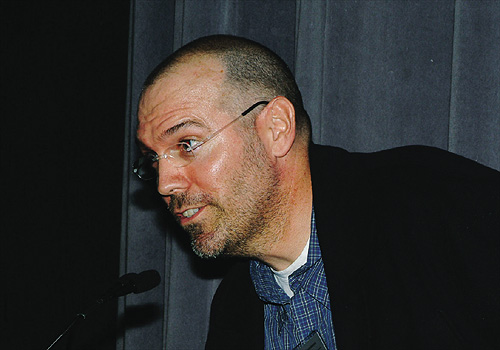

Nominated director Baker Smith at the DGA Commercial Nominees symposium. (Photo by Joe Coomber)

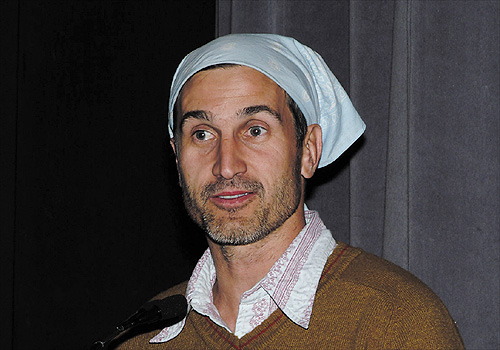

Nominated director Craig Gillespie at the DGA Commercial Nominees symposium. (Photo by Joe Coomber)

Nominee Noam Murro at the DGA Commercial Nominees symposium. (Photo by Joe Coomber)