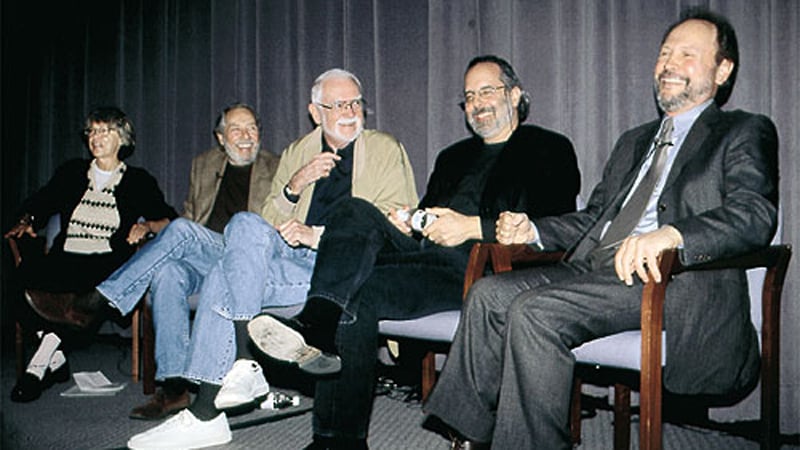

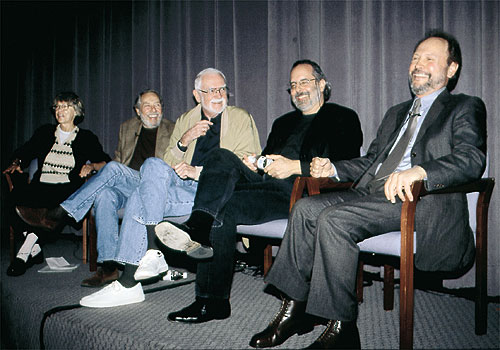

In one of her last appearances as First Vice President, before taking over as DGA President, director Martha Coolidge welcomed attendees to the Ninth Annual Meet the Nominees for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Movies for Television Symposium.

"I'm proud to say I'm a television director," Coolidge said. "No matter what the medium, a director must possess an extraordinary creative vision to produce an outstanding picture."

Coolidge applauded television directors for continuing "to deliver high-quality films in a medium that traditionally has less time, less money and more interference than their counterparts in feature films. The passion shown by these directors is the very reason the DGA has established creative rights that protect them, and it's why we so vigorously enforce these rights. It's also why we have our movies-for-television awards, so that they know that their passion and achievements will not go overlooked."

Director Joan Tewkesbury once again moderated the discussion. She said, "Movies are better than ever and they're on television."

What follows are highlights from the discussions with four of the final nominees. (Director Robert Allan Ackerman, nominated for Life With Judy Garland: Me & My Shadow, was unable to attend the event).

Uprising — Directed by Jon Avnet

— Directed by Jon AvnetAvnet first saw Uprising as a feature but had difficulty getting it made. Finally, after six years of persistence, and when it looked like actor and writer strikes were imminent, Avnet bought the underlying rights to the story from Disney and began to search for another route toward getting the project made.

"I really wanted to do this, and I realized I should do it in any form I can and get it to the largest audience," Avnet said. "I called up my friend, Steve White, who was at NBC where I had done The Burning Bed, and Scott Sassa, and asked them if they could let me know, within a day, whether they wanted to do it? I thought they might like the material. Otherwise I was going to go to HBO, which is actually more natural for this because they'll give a better budget. But I hadn't worked with HBO. I had worked with both these gentlemen and they said 'yes' the next day."

Having finally received his green light, another behind-the-scenes piece of luck came his way — Raffaella DeLaurentiis. "She came in to produce it for me and she's a genius. She made money and time come out of apparently nowhere."

Avnet was also lucky in his casting search. "I always start with one person and Leelee Sobieski was the key for me to tell the story. I wanted someone who captures one simple thing — an expression called 'Jewish eyes.' You could change anything, you could change your look when you went on the Aryan side from inside the Warsaw ghetto, but your eyes would never change. Having seen the horror of what was in the Warsaw ghetto, it immediately betrayed you to the Nazis, and the Nazis actually had a unit that would check people for their eyes. Leelee had the ability to mask her emotions. Hank Azaria was probably the second one. I tried to hire Hank when I was doing Up Close and Personal because I thought he, Redford and Pfeiffer would work well (together). He's an incredible actor, so I offered this role to him. I also did a lot of casting in England, which has an incredible pool of actors for my needs. I felt it important that there be a really European feel to the cast. To me it's much more difficult for Americans to believably play Europeans."

A trio of production designers worked on the re-creation of the Warsaw ghetto. Avnet first hired Alan Starsky (Schindler's List), who was very knowledgeable about the period. But a timing conflict with another production meant Starsky had to drop out, so Richard Silbert came on board.

"We knew it had to be massive, so he put together a design based on the way I needed to stage the big battle sequences. When we finally got the go ahead to make the movie, Dick wasn't available and I hired Benjamin Fernandez, who took Dick's plans and realized them. We built a 300-meter set, four stories high, hand-laid cobblestones and built roofs that were able to be burned down and blown up — it was an amazing design. Benjamin and two crews, one from the Ukraine, one from Croatia, built each side, almost like a competition."

One of the ghetto survivors, there to lend technical support on the film, was invited to the set one night by Avnet. "I brought him there at night, when the workers had all gone home. I thought it would be a pretty amazing thing for him to see this. I had no idea what his reaction would be. He walked into the middle of this square and stood there for about 45 seconds. He pointed up to one of the apartments and said,

'I lived there!' He had tears in his eyes and I went, 'Oh, boy!'"

Uprising was shot over 73 days by a trio of camera operators — Denis Lenoir, Chris Proust and Goran Mecava, working hand-held 95 percent of the time. "It was so physically demanding and some pretty tough stuff to look at and create and they were just there gunning, going. You can't say thank-you as a director. You feel it's too small."

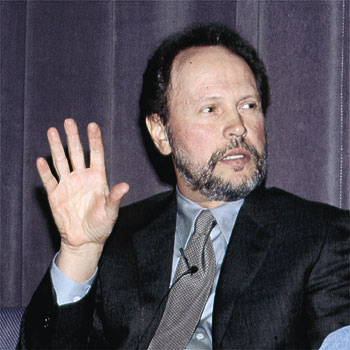

was shot over 73 days by a trio of camera operators — Denis Lenoir, Chris Proust and Goran Mecava, working hand-held 95 percent of the time. "It was so physically demanding and some pretty tough stuff to look at and create and they were just there gunning, going. You can't say thank-you as a director. You feel it's too small."61* — Directed by Billy Crystal

— Directed by Billy CrystalBilly Crystal's 61* took nearly 50 years to come to fruition. "This movie started pre-production in 1956 when I went to my first game at Yankee Stadium and saw Mickey Mantle hit a monumental legendary home run off the façade," Crystal said. A quick cut to more recent times revealed that Crystal and Mantle had become friends and among the stories Billy had heard was of the summer of 1961, when Mickey and Roger Maris shared an apartment in Forest Hills.

The Maris family had also relayed its own interesting stories, and Crystal felt this would be the basis for a good film. When he discovered there was already a script at HBO, Billy talked to Ross Greenburg who immediately sent it to him.

"It was very dark and sad and focused on Mickey's drinking and then flashed back." It didn't feel right for Crystal, and in talking to Greenburg he gave his own ideas "about Mickey and Roger living together and these delicious stories. Then I felt we had a movie that wasn't a baseball movie, but a movie about two rivals, ultimately friends, and the summer that would shape their friendship for the rest of their lives."

Finding the key to unlock the story had only been the answer to one of Crystal's problems. There still remained the daunting task of finding the right actors to portray such well-known legends. And those "right" actors would "have to throw better than Tony Perkins did in Fear Strikes Out," Crystal said.

Coincidentally, before he had even come on board the project, Crystal saw Barry Pepper in Saving Private Ryan. "The first shot of Barry, I turned to my wife and said, 'There's Roger Maris.'" Billy called Pepper who was reluctant, saying, "It doesn't look good for someone my age to do an HBO film." He worried how people would perceive the move to a telefilm at this stage in his career. Crystal talked him through it.

Crystal had also seen Thomas Jane in a couple of movies, and began to think: "Different parts of his face, that could be Mickey. Jane's not a big guy, but you can make him look big. He had a way about him."

However, when Jane came in for a meeting, Crystal was shocked. "Tom comes into my office, barefoot, long hair, just all messed up and smoking Gaulois ... and he's wheezing and I go, 'You have to play Mickey Mantle!'" The 30-year-old Jane didn't know anything about Mantle, who had stopped playing in 1968.

Fortunately, Crystal had "a great palette of film, tape and home movies of Mantle, interviews and stuff that people haven't seen. Not just the physical things that Jane would have to do, the human being he would have to play."

Once casting was approved, Crystal took Jane to former ballplayer Reggie Smith "at a little league field in Encino. Tom's smoking and wearing green sneakers and black socks!" Smith looked at Jane and told Crystal he couldn't effect the transformation in the available eight weeks, but two weeks later Reggie called Crystal and invited him to come out to the field.

"I drive out to the little league field and he's out there shagging fly balls, catching, throwing a ball, hitting from both sides of the plate — it's Mickey Mantle! I've never seen a transformation like this in my life. The videotape I have of him is spooky because Mickey used to call me 'you little son of a bitch' whenever he would see me. So Jane's catching balls and Reggie goes 'Mickey!' and he runs over with a little bit of a limp, all the sore leg syndrome and says, 'Hey, you little son of a bitch, how're you doin'?'"

Another important character in 61* was the stadium, which had to look right. "Yankee Stadium, with the façade, the short right field, the low wall, had to be re-created and we didn't have the budget to do it digitally, though there are some fantastic shots that are enhanced." Crystal turned to designer Rusty Smith. "Rusty went right to work. We had a fantastic array of photographs of the old stadium, both color and black-and-white, and we had my memory."

Even seats in the stadium were the same color, thanks to a paint chip taken from a chair Crystal had from the original Yankee Stadium. Completing the stadium's authenticity, his crew even built the monuments that used to be in center field at Yankee Stadium.

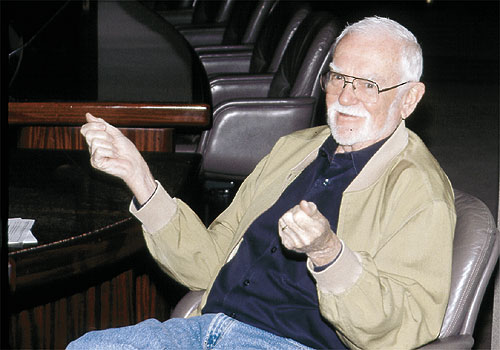

Conspiracy — Directed by Frank Pierson

— Directed by Frank PiersonFrank Pierson's connection with Conspiracy began 10 years ago when editor Peter Zinner, a friend and frequent collaborator, brought him a cassette of an Austrian film about a horrifying meeting between Nazi leaders. Zinner told Pierson, "We have to make this; we have to make an English version, because this story needs to be out in the world." Pierson was horrified, a Holocaust film told from the Nazi point of view! "But I was obliged to look at it because Peter's an old friend."

When Pierson and his wife, who's Jewish, sat down to watch it (despite her objections), they quickly became "fascinated; we couldn't stop looking at it. I took it to Bob Cooper, who was running HBO, and showed it to him. He bought it right away."

Development began and Loring Mandel, another old friend with whom Pierson had worked frequently, was brought in to do the screenplay. Before it could be completed there was a change of management at HBO. "Long and short of it, we went into development hell before it was finally abandoned," Pierson said.

A few more years spent trying to get the project off the ground, including interest from European entities, failed to advance the cause, "and then one of these people came up with enough money. I brought it back, on a hunch, to Colin Callendar at HBO and we went straight into developing a screenplay. There was no hesitation on HBO's part; in fact, they threw all their available resources into it, determined to get it made."

As records of the actual meeting were heavily edited, they had very little to work with and no dialogue. "There was no personalization or characterization of the people there. All that had to come from research, an enormous amount of research into trying to find out as much as we could."

The mansion where the events of the film actually transpired, is now a Holocaust museum. Pierson and his team were able to visit, and drawing upon research that had been done by the museum staff, were able to get a very clear sense of how that room was furnished at the time.

"Production designer Pete Mullins reproduced the interior of the whole first floor of the mansion on a sound stage at Shepperton," Pierson said. "It was designed so that it was about three feet over length and sides larger than the actual meeting room."

Since the cast was going to be in that room for 23 days, sitting around a table, Pierson wanted it to be as real for them as possible, ensuring the environment was not like a film set. He did not want a three-sided room with a fourth side featuring a bunch of guys sitting with earphones on, staring at monitors.

"The actors were in their costumes and in that room 10 hours everyday we were shooting and I think it gave a certain verisimilitude," he said. "They found it very, very depressing. We did huge takes. I would run the magazines out, over and over again, and that also gave a great advantage to them. They would really get into a performance instead of doing it in little bits and pieces. After awhile, the sense of it being a movie set began to just simply disappear as much as it possibly could."

James Dean — Directed by Mark Rydell

— Directed by Mark RydellMark Rydell's intimate knowledge of his subject went back nearly 50 years. "I felt a strong ethical and moral obligation to reveal Jimmy [Dean] as I knew him. I had a real advantage because we had been at the Actors Studio together in New York and we pounded the streets together looking for jobs. We shared a lot actually; we acted on television together. I felt, because I knew him so well, that I could bring a real value to this screenplay and to the insights that I wanted to reveal about him."

The idea for a James Dean film had been at Warner Bros. for about seven years, undergoing several drafts and seeing numerous directors come and go. TNT acquired the project from Bill Gerber, a friend of Rydell's and a former Vice President at WB. "He called me immediately and I was able to develop a new screenplay based on my intimate knowledge of Jimmy."

Rydell teamed with writer Israel Horowitz, "who's brilliant, charming, educated and prolific. We hit it off straight away. We spent months together working on the screenplay, adjusting it." In the end, Rydell believes they created a story about a father and son that works.

Rydell knew that finding the right actor to portray Dean was also going to be key to the project. "I told TNT when we started, 'This is a very strange situation. You're going to have to finance the preparation of this picture and prepare it as if we are going to make it. We're going to find locations, we're going to hire everybody but if I can't find Jimmy, I'm going to leave, because there's no way to achieve this picture without finding this incredible character.'

"I saw literally more than a hundred actors," Rydell said. But no one could give Rydell the James Dean he knew. Rydell was about to tell TNT he was going to pull out of the project when, "in walked James Franco, reluctantly, by the way. His agent told him not to do it. His manager said, 'Don't do it because it's a hopeless situation. You'll never be Jimmy Dean and even if you are good, you'll never live up to it.'

"I spent half an hour with him. Generally speaking, I don't like to read actors. I know that many actors can read well but can't create behavior to save their lives, and the converse is true — there are actors who can act brilliantly but can't handle the situation of reading. So I like to talk to them, spend some time with them and walk around the corner, have some coffee and ask them about their parents and school. The minute you start doing that with an actor all the fear, the anxiety, disappears and they'll reveal who they are, which is, after all, the raw material of what you're going to be working with. Jimmy [Franco] was very forthcoming, very honest and very passionately revealing of his life. I saw in the half hour that I had struck gold."

Rydell shot everything in and around Los Angeles. "It was quite an interesting challenge. The idea of shooting people shooting those classic films — East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, Giant — and our focus was on the process of making those films, more than the scenes themselves. In the film you never saw the actors without seeing old cameras and old lights. It was very carefully researched so that you were constantly seeing 'the way things happened.'"

Rydell's passion to get the process of filmmaking on screen is an extension of his overall passion about the medium and his love for directing. "Directing is a spectacular profession, one I have the deepest reverence for. It's very paternal. You have to provide an environment for all the talents surrounding you to give their best."

–Mike Reynolds