BY DAVID THOMSON

"King Vidor" — the name sounds like a character from a movie, a match for Darth Vader perhaps. It carries connotations of majesty and the Latin root for video, videre — to see. Vidor was a beloved figure in the industry and a famous director from the silent era to CinemaScope and beyond. He received five best director nominations and an honorary Oscar. More than that, he was a guiding force in the formation of the Screen Directors Guild (later the DGA), serving as its first president in decisive and difficult years. For his distinguished career, he was presented with the Guild's Lifetime Achievement Award in 1957.

It was not just that the boy was named "King" (after his uncle). On September 8, 1900, when he was 6 years old, winds of 135 miles per hour struck his home city of Galveston, Texas. There was spectacular devastation, and he was there to see it. "All the wooden structures of the town were flattened," he told Nancy Dowd and David Shepard in the DGA's oral history series (1980). "The streets were piled high with dead people, and I took the first tugboat out. On the boat I went up into the bow and saw that the bay was filled with dead bodies, horses, animals, people, everything."

No one knows exactly how many died in the Galveston hurricane. But the estimate of 8,000 is more than four times the number lost to Katrina. Vidor saw this as a child, and when his father encouraged him to go into business, King said he thought he would be a photographer instead and record extraordinary things.

In that biographical sketch lies the impulse behind a career based on surprise and Vidor's ease at moving from grandeur to humbleness. If it is a test for any boy to be named "King," then it was a formative lesson to behold human vulnerability so early. Fifty years later, that feeling of the frailty of life was still present in his next to last film, War and Peace (1956), in which a haggard Napoleon in Moscow realizes his triumph and doom. All of Vidor's films were full of his dynamic cinematic confidence and the sense of being in charge of the greatest storytelling machine of his time.

Vidor described the process of directing this way to his fellow filmmaker Alan Pakula: There are "a hundred people around the camera [and] that one fellow, the only person who can say yes or no. It all has to be filtered through one person to have it work at all. And it's my belief that it's just as personal as writing a book or painting a picture."

Apart from his extraordinary career as a filmmaker, the reason to honor Vidor is the role he played in the foundation of the Directors Guild. This is a story worth telling, and one that points to the ever-changing status of the director. It's too easy to think of the 1930s as a happy "golden age." Rather, it was an era of desperate confusion in which no one was sure of the future.

At that time, the public hardly knew anything about directors, and there were studio bosses - even those as sympathetic as Irving Thalberg - who disputed a director's authority. Sound had come to the picture business both as a blessing and a disaster and the industry required infrastructural investment just when American money was drying up. The Crash of 1929 was followed by years of sinking economic depression. In the early '30s, the size of the audience withered. The studios faced ruin. Not long after the 1933 inauguration of Franklin Roosevelt, the studios threatened drastic pay cuts.

For several years, the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences had attempted to act as arbiter between management and labor, but was rightfully regarded as a forum for the studios. After a meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel about the cuts called by the Academy, about six or eight directors congregated on the sidewalk outside the hotel. "The realization was very strong," Vidor recalled, "that we must have an organization to speak for us."

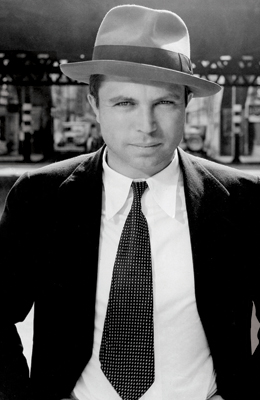

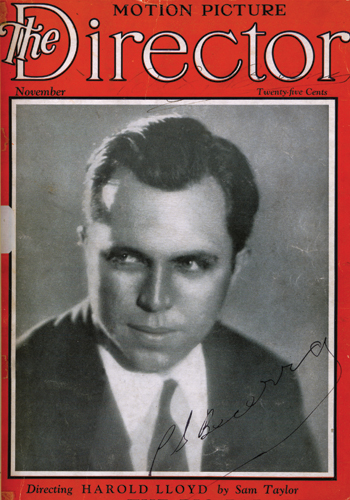

LABOR LEADER: Vidor was an active member of the MPDA when he

LABOR LEADER: Vidor was an active member of the MPDA when he

appeared on the cover of its magazine in 1926. Vidor introduced his archetype of the common man in

Vidor introduced his archetype of the common man in

the silent classic The Big Parade.He became a leader in the search for unity among directors. Informal talks led to a meeting on Dec. 24, 1935 of a dozen or so directors at Vidor's house in Beverly Hills. The Screen Directors Guild was incorporated on Jan. 13, 1936, and its 29 members elected Vidor as their first president. The Guild was not over-reaching in its claims. It sought more time in preproduction, a proper chance to examine a script before filming, and the right to make at least a first cut.

Despite the bitter opposition of studio bosses, Vidor used his standing in the industry and power of persuasion to lobby other directors to join the Guild, but it wasn't easy. Vidor, like the other founders, understood that strength—and acceptance by the studios—lay in numbers. To accomplish his goal, he recognized how important it was for the Guild to include all the top directors, whether on the left or the right. In this regard, Vidor targeted the far right-leaning Cecil B. DeMille, one of the most powerful directors of the time.

Vidor and DeMille had history together. In 1931, DeMille had enlisted Vidor and several other directors in a failed plan to produce and distribute films independently. At the first general membership meeting of the new Guild at the Hollywood Athletic Club on Jan. 22, 1936, DeMille was dismissive, if not downright hostile to the new organization. His main concern was that the directors would align with the already organized writers and actors who had brought their organizations under the umbrella of what he considered the "Bolshevik" American Federation of Labor. Two days after the meeting, the SDG announced that it would not affiliate. Vidor understood that he would need DeMille for bigger battles ahead, and thanks, at least partially, to his practical politicking, DeMille was not permanently alienated from the Guild, and became a member in 1939.

Meanwhile, Vidor continued to implore members to join. Under his leadership (1936-38), he brought assistant directors into the ranks in 1937, and in two years membership rose to about 600, including virtually every active director and assistant director. In a recruiting letter he sent to Ernst Lubitsch, he wrote, "The Screen Directors Guild was organized solely by and for the Motion Picture Director... We are not anti-anything: The Guild being formed for the purpose of assisting and improving the director's work in the form of a collective body, rather than as an individual, as was necessary in the past." Other directors got a harder sell. Co-founder Rouben Mamoulian recalled that he and Vidor started taking different directors to lunch or dinner and shaming them into joining.

One of the toughest sells was Frank Capra, who, as one of Hollywood's hottest young directors, Vidor saw as essential to establishing the Guild's legitimacy and ability to negotiate a contract with the studios. To this point, Capra had been aligned with the pro-studio Academy, even serving as its president in 1935. In a 1985 interview, quoted in Joseph McBride's Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, Capra recalled Vidor demanding, "Frank, what the hell are you breaking your ass about the Academy for? Why don't you want to do anything for the directors?"

With that kind of "encouragement," Capra eventually realized his heart was more with the directors and signed up in July 1937, going on to become Guild president and spearheading its drive for studio recognition. Finally, in 1939, Capra was able to accomplish what Vidor had started and the studios signed an accord with the Guild.

As he was first building the case for the Guild among other directors, Vidor recalled in a 1977 interview with labor historian Mitch Tuchman, quoted by McBride, that "When you'd talk to somebody, they'd say, 'Well this is a Communist inspired thing.' That's what you'd hear a lot of." Vidor himself was a likely target. His film Our Daily Bread (1934) was plainly a plea for rural cooperatives to serve as a refuge for dispossessed city people. The film was made after Vidor had read a Reader's Digest article proposing collectives and the abandonment of money. He wrote a script (with his third wife, Elizabeth Hill) and took it to Thalberg, who had been his patron on the silent classics The Big Parade (1925) and The Crowd (1928) at MGM.

In Vidor's account, Thalberg said "it was darned interesting, but he didn't think he could approve it for the studio." The script contained impoverished characters and a sharp attack on the banking system, but Vidor said he could not understand why that disturbed Thalberg. So acting as a producer, Vidor raised the money personally, $125,000 from the Bank of America, and released the film through United Artists thanks to the support of Charlie Chaplin. To this day, Our Daily Bread is cited as a rare example of socialism in American film in which people overcome drought, foreclosures, and isolation.

We are close here to the contradictory temperament of King Vidor, a populist on one hand but the director of The Fountainhead (1949) on the other, and, in 1944, a founding member of the anti-Communist group the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Raymond Durgnat and Scott Simmon, who explore this paradox in their book King Vidor, American, note that Our Daily Bread was also criticized by the left in its day as the very opposite of socialism, for its support of decisive, strong leadership. There is no question that in The Fountainhead Vidor endorsed (and exulted in) Ayn Rand's portrait of architect Howard Roark, who, when his independence is challenged, is ready to defy public opinion even to the point of destroying his own building. Vidor worked to organize and promote directing, but believed directors would always have to struggle to defend their vision. In many ways, that's why Roark embodied the essential Vidor hero.

But Vidor was not naïve. He worked all his life in the picture business and was close enough to Thalberg to have secured profit participation on The Big Parade - 20 percent, as Vidor claimed in his autobiography, A Tree Is a Tree. At the same time, there was an innocence and a melodramatic passion to the man that says so much about early Hollywood, and the heady feeling that at last stories could be made for everyone."

"There is the story in every man's heart of human progress," Vidor wrote. "I believe every one of us knows that his major job on earth is to make some contributions, no matter how small, to this inexorable movement of human progress." It's when you put Vidor's sunny optimism together with his extraordinary early achievements in film that you can see how vital he was to the advancement of the Guild. In his remarks to a memorial gathering at the time of Vidor's death in 1982, then-Guild president Jud Taylor said, "We will always be in debt to our first president who, back in 1936, joined others who had the courage to put their personal and professional prestige and careers on the line for all of us who followed. Without the clarity of vision and deep sense of commitment that King gave to his work..., this organization that protects and provides for its members might never have become a reality."

There were other great directors in the '30s, to be sure, but Vidor had a boundless cheerfulness. He talked about the common man and introduced that archetype in films such as The Big Parade and The Crowd. He was presidential material and the Guild was his natural forum.

King Vidor was of Hungarian descent, the child of a well-to-do family, who put aside thoughts of the lumber business or studying past high school to pursue filmmaking. As a teenager, he was shooting newsreels and helping to run a Galveston movie theater. By 1915, with his first wife Florence, whom he wanted to make a silent film star, he left for Los Angeles.

DOWN HOME: The Crowd was one of the boldest departures

DOWN HOME: The Crowd was one of the boldest departures

in American silent pictures.  Vidor drew on his childhood in Texas for the all-black musical Hallelujah!

Vidor drew on his childhood in Texas for the all-black musical Hallelujah!  Vidor's house in Beverly Hills where the Guild was born in 1935.

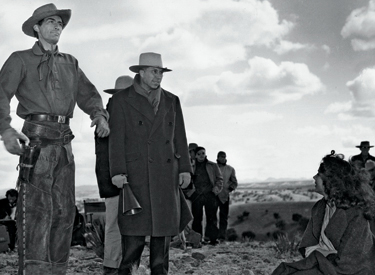

Vidor's house in Beverly Hills where the Guild was born in 1935.  Directing Gregory Peck in Duel in the Sun.

Directing Gregory Peck in Duel in the Sun.

(Photo Credits: Bison/Everett/LAPL/King Vidor Collection)Friends warned him it was a terrible place, but he was determined to put Florence on film, and was soon crawling under a fence to watch D.W. Griffith shoot part of Intolerance. "The whole thing to me was just one great Disneyland. It was a place I wanted to be, and I wanted to be a part of it." Vidor was, more or less, the same age as the movies, and he grew up with them. "At first I did anything - extra work, bit parts, writing, anything that had to be done just to learn...," he said. Finally, I wrote a script [The Turn in the Road, in 1919] and sent it around... and nine doctors put up a $1,000 each... and it was a success. That was the beginning. I didn't have time to go to college."

Throughout his career Vidor believed in an America where will, desire, and effort would carry anyone through. After all, he was working in a business and an art that had no traditions: "I told Florence that I knew how to direct films. And she said, 'How can you say that? You haven't even been in the studio more than a few times.' Well, I sort of felt that I wanted to be a director. Just to be in a studio. That's how important it was to me."

Unfortunately, many of his early silent pictures have not survived, but he was lucky enough to arrive at MGM at the same time as Thalberg. And in his own words, here is Vidor's voice of unstoppable innocence: "One day [in 1925] I had a talk with Irving Thalberg and told him I was weary of making ephemeral films. They came to town, played a week or so, then went their way to comparative obscurity or complete oblivion. I pointed out that only half the American population went to movies and not more than half of these saw any one film because their runs ended so quickly. If I were to work on something that I felt had a chance at long runs throughout the country or the world, I would put much more effort, or love, into its creation. "Thalberg replied that my wishes were certainly in line with his own. Then he asked if I had any ideas commensurate with this ambitious goal. I said I had. I would like to make a film about any one of three subjects: steel, wheat, or war... [and] he suddenly asked if I had a particular war story in mind.

This was how The Big Parade (1925) began. It would be the making of its star, John Gilbert, and of Vidor, too. It was also part of the great surge that established Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a studio aiming at the best pictures in town. The film ran over two hours and cost about $245,000; no matter that Thalberg authorized Vidor to re-shoot a scene involving trucks, armies and aircraft just to secure the dramatic impact of a dead-straight road. The film was a huge hit, collecting about $20 million at the boxoffice worldwide, and until the release of Gone with the Wind, was the studio's highest grossing picture. These unprecedented numbers helped sustain the studio's other major production of the year, Ben-Hur, which actually lost money (it cost 10 times more than The Big Parade).

The success of The Big Parade turned Vidor into a top asset at MGM. For the moment, he left wheat and steel on the shelf, only to prove that he could do nearly anything asked of him. La Bohème (1926), with Gilbert and Lillian Gish, was flawless romance; Bardelys the Magnificent (also 1926) was costume drama, with Gilbert and Vidor's second wife, Eleanor Boardman. Then came The Crowd (1928) - one of the boldest departures in American silent pictures.

According to Vidor's autobiography, The Crowd grew out of another chat with Thalberg. "What next?" asked the mogul. Vidor improvised: "Well, I suppose the average fellow walks through life and sees quite a lot of drama taking place around him. Objectively life is like a battle, isn't it?" Thalberg then replied, "Why didn't you mention this before?" The producer added that he reckoned the studio could afford an experimental picture.

For The Crowd, Vidor cast Boardman and James Murray, an extra he had noticed on the lot. The film is an everyday tragedy that turns into an uplifting fable, and its ordinariness is offset by sumptuous camera movements and a Germanic command of visual drama (Vidor was very much affected by Metropolis and The Last Laugh). The film made only a modest profit, but in the first year of the Academy Awards it was nominated for "Artistic Quality of Production" (awarded just that one year).

So what did Vidor do next at Metro? Two delicious Marion Davies comedies, The Patsy and Show People (both 1928). This was followed by Vidor's first sound film, the all-black musical Hallelujah! (1929), a highly risky, personal project he had been trying to make for some time in which he invested his own salary. "It was just a complete thing of my Texas and Arkansas childhood," Vidor said in a 1975 interview. "Baptisms, and the river, and sawmills, and religious meetings, and shoutings, the whole thing. You're just calling upon your semiconscious all the time to fill in all these things. Even the script was written just by listing all my memories of childhood."

In the challenging years leading up to the Guild's foundation, with directors trying to assert themselves, Vidor branched out. He began working with two independent producers - Samuel Goldwyn and David O. Selznick - with mixed results. Then in 1938, he returned to MGM and yet again, the work is extremely unpredictable. The Citadel (from the A.J. Cronin novel) is a story of doctors battling poverty in a Welsh mining community, involving the deliberate destruction of a bad sewage system oddly predictive of The Fountainhead.

Vidor experimented with color for the first time in Northwest Passage (1940), an epic, landscape Western. The best of his MGM films from this period is the least known, An American Romance (1944). This is the steel movie, with a raw immigrant (Brian Donlevy) becoming a miner and then a huge American success. The film did no business, perhaps because of lengthy documentary-like sequences of factories at work. It may have needed Vidor's first choice, Spencer Tracy, instead of Donlevy, but is dynamic and intensely beautiful. With that film alone, Vidor deserves to be appreciated as an uncritical poet of American opportunity and achievement.

During that second MGM stint Vidor also presided over the "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" song from The Wizard of Oz (1939) as Victor Fleming hurried off to take over Gone with the Wind. The song was already written, of course, just as Judy Garland was cast. Vidor may have simply executed the script. But look at the scene again, feel the subtle camera movements and ask whether anything in that classic is more touching or more filled with prairie yearning. It was the kind of thing a pro did, without credit, according to the studio system. In 1945, Vidor was only 51, with four nominations for best director and a handful of classics to his name. Yet the biggest and most radical of his films were still to come. First, he was reunited with Selznick on Duel in the Sun (1946), a Western that was one of the most lurid and painterly of Technicolor pictures, and a vehicle for Jennifer Jones and the adoration Selznick felt for her.

Vidor talked about directing Jones, and it reveals a lot about his way with actors, an approach formed in silent pictures: "We had to start each day by telling her the story from the beginning... In other pictures when she tried to act, she wouldn't arrive at it from the inside. She made a lot of grimaces, and the effort on her part became very obvious. I discovered that if we worked up to it gradually, she would sustain that special quality all day."

But this took too long, especially with Selznick's constant memos. Selznick interfered so much that one day the frustrated Vidor walked off the set and never came back. Sometimes directors had to say no. Whereupon, Selznick pushed in two reels of back story, and hired William Dieterle and Josef von Sternberg as "advisers." The film still has scenes - like the sado-masochistic conclusion where Jones and Gregory Peck kill each other in a harsh rocky landscape - that are a novel injection of disturbed psychology in the Western genre. It is the model of Hollywood going over the top - yet it would not be as vivid without Vidor.

But Duel in the Sun fades when put beside The Fountainhead, based on the Ayn Rand novel. A conventional script was written, but when it proved unsatisfactory, Rand took up the task for free - as long as no one messed with her dialogue. Humphrey Bogart was the first choice as the hero, but he gave way to Gary Cooper. The role of the heroine was meant for Barbara Stanwyck, but in the end the role went to newcomer Patricia Neal. Vidor could see that she and Cooper were falling madly in love and was able to capture their chemistry on screen.

PERSONAL TOUCH: Charting the fate of a willful architect in The Fountainhead,

PERSONAL TOUCH: Charting the fate of a willful architect in The Fountainhead,

with Gary Cooper and Patricial Neal.  Capturing the frailty of human endeavor in War and Peace,

Capturing the frailty of human endeavor in War and Peace,

with Herbert Lom as Napoleon. (Photo Credits: Everett; AMPAS)The movie was released in June 1949, and it was another hit for Vidor, but it was not reviewed kindly. Some people laughed at the scene where the hero drilling in a quarry penetrates the sleep and the mind of the heroine. So be it. In the late '40s, there was a new fashion for realism and a hope for social responsibility that Ayn Rand scorned. These days, the film's mysterious or unexplained lack of inhibition feels modern. The glorification of the intransigent artist hero is more understandable, and the disdainful portrait of a world of compromise has fallen into place. It's clear now that The Fountainhead is a dream or parable, utterly averse to the common man, pledged to genius for its own sake. It may be King Vidor's finest movie, a characteristic fusion of vivid action and high ideas.

Although it was a project that came to him through the Warner Bros. transom, as it were, it coincided with Vidor's thinking about the individual at the time. In his oral history, he mentions that he had been rereading Carl Jung's Psychology of the Self at the time and had gone through Jungian analysis just a few years earlier. "I was then very conscious of this recognition of self... What has all this to do with filmmaking? Everything. It is your world. You do not see it through the lens of a camera, you make it with the lens of a camera. You don't see with the eye, but through the eye.

The conventional view is that Vidor's career declined after The Fountainhead. But Beyond the Forest (1949), with Bette Davis, has to be seen to be believed. Vidor and the actress did not get on well, but the lyrical melodrama and mix of ugliness and passion in Davis' character, a Midwest Emma Bovary, is more impressive than the film's reputation suggests. Vidor's War and Peace was not a hit while Ruby Gentry (1952) is regarded as a tame remake of Duel in the Sun. Solomon and Sheba (1959), his last picture, was hurt by the death of Tyrone Power during shooting, though one doubts it ever had a chance of working. And yet, War and Peace has amazing spectacle. It also has an assurance that says well, sure, why not have the nerve to do War and Peace in 208 minutes? The producer, the late Dino de Laurentiis, wanted Henry Fonda for box-office reasons; Vidor, on the other hand, wanted Peter Ustinov - overweight, anti-heroic, and very European. "I think he would have given the film more stature," said Vidor. Relatively late in his career, Vidor still risked losing battles with the powers that be.

Vidor stopped directing commercial pictures after Solomon and Sheba. He had other projects - a film about Cervantes and a version of Hawthorne's The Marble Faun - but he admitted he wasn't cut out to be an independent producer. "I'm glad I got out of it," he said. "They were diluting every idea, changing everything... In The Fountainhead Gary Cooper blows up the whole building because they change the façade and some of the other sections of the structure. That's what I felt like at that point."

Later on, he used his own 16 mm camera to make two abstract studies - Truth and Illusion (1964) and The Metaphor (1980), the latter with painter Andrew Wyeth. Ever since The Crowd, Vidor had been fascinated with the notion that movie action depended on inner metaphor. Vidor had a ranch in Paso Robles and a cottage in Los Angeles. It was natural that he should teach (at USC for 10 years) and write. He did detective research on the old William Desmond Taylor Hollywood murder case from 1922, which eventually turned into Sidney Kirkpatrick's book, A Cast of Killers (1986). In 1981, he took a supporting role in James Toback's Love and Money - and played it with great charm. It was in 1979 (the year of The Deer Hunter, a Vidor-like picture with its stress on ordinary yet extraordinary characters) that he received an honorary Oscar "for his incomparable achievements as a cinematic creator and innovator."

That tribute seems dry or too modest. King Vidor belonged to the generation that made Hollywood. He excelled as an individualist at a great studio, and while he was a lifelong spokesman for the creative rights of directors, he seemed to thrive in the studio structure. His range of material hardly has a rival - Howard Hawks is the only other director who comes to mind. And Hawks, like Vidor, was rather taken for granted in his lifetime. The scope from The Crowd to The Fountainhead seems farfetched, but a similar stretch exists between Show People and The Big Parade, War and Peace and Beyond the Forest. Nothing holds Vidor's energized untidiness together except his inexhaustible appetite for storytelling, his assurance, and his curiosity. He was stirred by great sights and by the camera's power to share them with people who had not witnessed things like the Galveston hurricane, the retreat from Moscow, the gaudy splash of an Arizona sunset. Like every great director of that first age of film, he taught us to see.